Roger Ebert’s best movie lists from 1967-present

Roger Ebert’s best movies of all time

How in the world can anyone think it was a bad year for the movies when so many were wonderful, a few were great, a handful were inspiring, and there were scenes so risky you feared the tightrope might break? If none of the year’s 10 best had been made, I could name another 10 and no one would wonder at the choices. There were a lot of movies to admire in 2005. These were the 10 best:

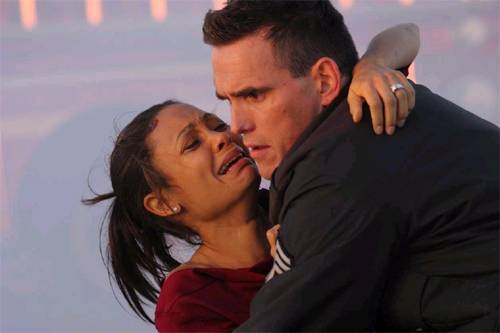

1. “Crash“: Much of the world’s misery is caused by conflicts of race and religion. Paul Haggis’ film, written with Robert Moresco, uses interlocking stories to show we are in the same boat, that prejudice flows freely from one ethnic group to another. His stories are a series of contradictions in which the same people can be sinned against or sinning. There was once a simple morality formula in America in which white society was racist and blacks were victims, but that model is long obsolete. Now many more players have entered the game: Latinos, Asians, Muslims, and those defined by sexual orientation, income, education or appearance.

America is a nation of minority groups, and we get along with each other better than many societies that criticize us; France has recently been reminded of that. We are all immigrants here. What is wonderful about “Crash” is that it tells not simple-minded parables, but textured human stories based on paradoxes. Not many films have the possibility of making their viewers better people; anyone seeing it is likely to leave with a little more sympathy for people not like themselves. The film opened quietly in May and increased its audience week by week, as people told each other they must see it.

2. “Syriana“: Stephen Gaghan’s film doesn’t reveal the plot, but surrounds us with it. Interlocking stories again: There is less oil than the world requires, and that will make some rich and others dead, unless we all die first. The movie has been called “liberal,” but it is apolitical, suggesting that all of the players in the oil game are corrupt and compromised, and in some bleak sense must be, in order to defend their interests — and ours.

The story involves oil, money and politics in America, the Middle East and China. The CIA is on both sides of one situation, China may be snatching oil away from us in order to sell it back, and no one in this movie understands the big picture because there isn’t one, just a series of tactical skirmishes. “Syriana” argues that in the short run, every society must struggle for oil, and in the long run, it will be gone.

3. “Munich“: Stephen Spielberg’s film may be the bravest of the year, and it plays like a flowing together of the currents in “Crash” and “Syriana,” showing an ethnic and religious conflict that floats atop a fundamental struggle over land and oil. Working from a screenplay by Tony Kushner, Spielberg begins with the massacre of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympiad of 1972, and follows a secret assassination team as it attempts to track down the 11 primary killers. Nine eventually die, but not before the Israeli (Eric Bana) who leads the team loses his moral certainty and nearly his sanity, and not before the film sees revenge as a process that may have harmed Israel more than its targets.

The film is not critical of Israel, as some believe, but a more general mourning for the loss of idealism in a region marching steadily toward terrorism and anarchy. In defending itself, can Israel afford to compromise its standards — or afford not to? Spielberg doesn’t have the answer. He has the courage to suggest that some of Israel’s post-Munich policies have not made it a better or safer place.

4. “Junebug“: At last, a movie about ordinary people. Or put it this way: Phil Morrison’s “Junebug” was the best non-geopolitical film of the year. In simply human terms, there was no other film like it. It understands, profoundly and with love and sadness, the world of small towns; it captures ways of talking and living I remember from my childhood, and has the complexity and precision of great fiction.

The story, written by Angus MacLachlan, involves Alessandro Nivola and Embeth Davidtz as Chicagoans who return to North Carolina to visit his family: His mother (Celia Weston), mercilessly critical of everyone; his father (Scott Wilson), who has withdrawn into his wood-carving; his brother (Benjamin McKenzie), who loves his wife but has been brought to a halt by his demons and shyness, and the pregnant wife (Amy Adams), who is a good soul.

“Junebug” is a great film because it is a true film. It understands that families are complicated, and their problems are not solved during a short visit, just in time for the happy ending. Families and their problems go on and on, and they aren’t solved, they’re dealt with. There is one heartbreaking moment of truth after another, and humor and love as well.

5. “Brokeback Mountain“: Two cowboys in Wyoming discover to their surprise that they love each other. They have no way to deal with that fact. Directed by Ang Lee, it’s based on a short story by E. Annie Proulx and a screenplay by Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana. In the summer of 1963, Ennis (Heath Ledger) and Jack (Jake Gyllenhaal) find themselves one night on a distant mountainside suddenly having sex. “You know I ain’t queer,” Ennis tells Jack after their first night together. “Me, neither,” says Jake. But their love lasts a lifetime and gives them no consolation, because they cannot accept its nature and because they fear, not incorrectly, that in that time and place they could be murdered if it were discovered. Oh, what a sad and lonely story this is, containing what truth and sorrow.

6. “Me and You and Everyone We Know“: The previous films have waded fearlessly into troubled waters. Miranda July’s walks on them. It’s a comedy about falling in love with someone who speaks your rare emotional language of playfulness and daring, of playful mind games and bold challenges. July writes, directs, and stars.

In her first film, she trusts a delicate sense of humor that negotiates situations that would be shocking if they weren’t so darn nice. Can you imagine a scene involving teenage sexual experimentation that is sweet and innocent and not shocking at all, because it’s not about sex but about what funny and lovable creatures we humans can be? And when have you seen a woman seduce a man not with sex but with unbridled and passionate whimsy?

7. “Nine Lives“: Rodrigo Garcia’s film involves nine stories told in a total of nine shots. It is not a stunt. Most audiences will probably never notice that each scene is told in one shot, although they will sense the tangible passage of real time. The best story involves Robin Wright Penn and Jason Isaacs as two former lovers, now married to others (she pregnant), who meet by chance in a supermarket and during a casual conversation, realize that although their lives are content, they made the mistakes of their lifetimes by not marrying each other. Stating this so boldly, I miss the subtle sympathy that Garcia has for all of his characters, who are permitted those tender moments of truth by which we learn what a tease life is — so slow to teach us how to live it, so quick to end.

8. “King Kong” (2005): A stupendous cliffhanger, a glorious adventure, a shameless celebration of every single resource of the blockbuster, told in a film of visual beauty and surprising emotional impact. Of course, this will be the most popular film of the year, and nothing wrong with that: If movies like “King Kong” didn’t delight us with the magic of the cinema, we’d never start going in the first place.

Peter Jackson’s triumph is not a remake of the 1933 classic so much as a celebration of its greatness and a flowering of its possibilities. Its most particular contribution is in the area of the heart: It transforms the somewhat creepy relationship of the gorilla and the girl into a celebration of empathy, in which a vaudeville acrobat (Naomi Watts) intuitively understands that when Kong roars he isn’t threatening her but stating his territorial dominance; she responds with acrobatics that delight him, not least because Kong has been a gorilla few have ever tried to delight. From their relationship flows the emotional center of the film, which spectacular special effects surround and enhance, but could not replace.

9. “Yes” (2005): An elegant Irish-American woman, living with a rich and distant British politician, makes eye contact with a waiter. Neither turns away. Their sex is eager and makes them laugh. They are not young; they are grateful because of long experience with what can go wrong. He was a surgeon in Lebanon. Sally Potter tells their story in iambic pentameter, the rhythm of Shakespeare. The dialogue style elevates what is being said into a realm of grace and care.

Joan Allen stars, and has ever a movie loved a woman more? To recline at the edge of the pool in casual physical perfection is natural to her, disturbing to him. They realize they cannot live together successfully in either of their cultures. A third place is required. Their story is told in counterpoint with the bold asides of a cleaner (Shirley Henderson) who notes that for all their passion they shed the same strands of hair and flakes of skin and tiny germs as the rest of us, and must be cleaned up after. Bold, erotic, political, and like no other film I have ever seen.

10. “Millions“: The best family film of the year is by the unlikely team of director Danny Boyle and writer Frank Cottrell Boyce. Nine-year-old Anthony Cunningham and his 7-year-old brother, Damian (Lewis McGibbon and Alex Etel) find a bag containing loot that bounced off a train and is currently stuffed under their bed. With limitless imagination and joy, the film follows the brothers as they deal with their windfall.

Oh, and Damian gets advice from saints, real ones. St. Francis of Assisi, his favorite, provides advice that Anthony is sure will get them into trouble. Despite how it sounds, this isn’t a “cute little film.” The director makes hard-boiled movies, the writer has worked at the cutting edge, and this is what a family film would look like if it were made with the intelligence of adults.

The Jury Prize

At film festivals, the “jury prize” is how some jury members urgently signal that this is the film they like better than the eventual winner. It’s not second place but somebody’s idea of first place. Listed alphabetically:

“The Best of Youth,” by Marco Tullio Giordana, the story of two Italian brothers and their lives from 1963 to 2000, as they intersect with politics and history: The hippie period, the disastrous flood in Florence, the Red Brigades, kidnappings, hard times and layoffs, and finally a certain peace.

“Broken Flowers,” by Jim Jarmusch. Another inward, intriguing performance from Bill Murray, as a millionaire who lives in isolation and loneliness until he learns he might once have fathered a child, and visits the possible mothers.

“Cinderella Man“: Russell Crowe gives another strong performance in the comeback story of boxer Jim Braddock, who was washed up after an injury but fought back from poverty to win the heavyweight title from the dreaded Max Baer. Crowe’s accomplishment is to play Braddock as a good man, even-tempered, loyal to his family above all.

“Downfall,” by Oliver Hirschbiegel. We do not recognize Bruno Ganz, hunched over, shrunken, his left hand fluttering behind his back like a trapped bird. This is Adolf Hitler in his final days in the bunker beneath Berlin, where after his war was lost, he waged it in fantasy. Pounding on maps, screaming ultimatums, he moved troops that no longer existed and issued orders to commanders who were dead. A chilling portrait of evil and madness.

“Duane Hopwood,” by Matt Mulhern. David Schwimmer gives a career-transforming performance as an Atlantic City pit boss who loves his wife and children, and is losing everything because of alcoholism. Not the sensational drunk scenes of melodrama, but the daily punishment of the disease: Sometimes he drinks way too much. Sometimes he drinks too much. Sometimes he drinks almost too much. Sometimes he doesn’t drink enough. Those are the only four sometimes for an alcoholic.

“Good Night, and Good Luck,” by George Clooney. David Strathairn stars as Edward R. Murrow, who with his CBS News colleagues helped to bring about the downfall of the demagogue Sen. Joseph McCarthy. Shown in archival footage, McCarthy is a liar and a bully, surrounded by yes-men, recklessly calling his opponents traitors; he destroys others, and then is destroyed by the truth.

“Match Point,” by Woody Allen. A return to greatness for Allen, not with a “Woody Allen picture” but with a thriller based on stomach-churning guilt. (It opens Jan. 6 in Chicago.) Jonathan Rhys-Meyers is a poor, ambitious tennis pro who marries well (to rich girl Emily Mortimer) while dallying with Scarlett Johansson, the former fiancee of his brother-in-law. Can he solve his problems with a perfect murder?

“North Country,” by Niki Caro. Another powerful performance by Charlize Theron, as a working mother who becomes a miner on the Minnesota iron range and becomes the target of her male fellow union members. Based on the true story of the woman who inspired the first class-action lawsuit on sexual harassment. With great supporting work by Frances McDormand.

“The New World,” by Terrence Malick. A visionary story of Pocahontas (Q'orianka Kilcher) that places her, John Smith (Colin Farrell) and John Rolfe (Christian Bale) in an unspoiled sylvan forest, where the Indians live in harmony with the land and the English blunder in with guns and ignorance. Pocahontas falls in love with Smith, and her transformation leads to an unimaginable personal journey. (It opens Jan. 13 in Chicago.)

“The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada,” directed by and starring Tommy Lee Jones (best actor, Cannes 2005). He plays a ranch hand whose Mexican friend is killed by a border patrolman (Barry Pepper). He forces the younger man to join him on a long journey with the body, to the friend’s birthplace, in a film that could have been directed by John Huston and starred Humphrey Bogart. (Opens Feb. 3.)

“Pride and Prejudice,” by Joe Wright. Keira Knightley is the first among equals in a gifted cast that captures all the charm and romance of the Jane Austen novel. Set a little earlier and closer to the land than most Austen adaptations, so that the urgency of a fortunate marriage is underlined, and the characters seem less precious. Gloriously romantic.

Special Jury Awards

Festivals also hand out special awards for excellence, and so do I, because, in the words of Mickey Spillane, “I, the Jury.” Alphabetically:

“The Ballad of Jack and Rose,” Rebecca Miller’s film about an aging hippie (Daniel Day-Lewis) and his daughter (Camilla Belle), living in isolation on an island.

“Batman Begins,” the best and darkest of the Batman pictures.

“Bee Season,” with its wondrous performance by Flora Cross as a young girl with mystical gifts.

“Cache,” the French thriller about a family that knows it is being watched — but not why, or by whom, or how. (Opens Jan. 13.)

“Capote,” with Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Oscar-bound performance as Truman Capote.

“The Constant Gardener,” with Ralph Fiennes and Rachel Weisz stumbling across reckless programs to test drugs in Africa.

“Fear and Trembling,” with Sylvia Testud, who takes a job in Japan and finds herself a definitive outsider.

“Firecracker,” Steve Balderson’s brilliant indie about a murder in small-town Kansas.

“Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire,” with Harry surviving not only Voldemort but his first school dance.

“Head-On,” a harrowing portrait of Turkish “guest workers” in Germany and their desperation.

David Cronenberg’s “A History of Violence,” with Viggo Mortensen as a small-town diner owner who is pulled back roughly into his past.

“Hustle and Flow,” with Terrence Howard’s great turn as a pimp who transforms himself through art.

“Last Days,” Gus Van Sant’s uncompromising look at the decline and death of a character based on Kurt Cobain.

“Lord of War,” vibrating with the energy of Nicolas Cage‘s performance as a freelance arms dealer.

“The Memory of a Killer,” with Jan Decleir as an aging Italian hit-man, undertaking a last assignment although senility is approaching.

“The Merchant of Venice,” another reminder of Al Pacino’s passion and fierce focus.

“Mysterious Skin,” about growing up gay in Kansas and thinking maybe aliens were involved.

“Oldboy,” from Korea, about a man who is kept prisoner for 15 years for reasons he cannot imagine.

“Palindromes,” Todd Solondz’s challenging use of eight different actors in an examination of the moral complexities of abortion.

“Proof” (2005), with Gwyneth Paltrow as the daughter of a great mathematician (Anthony Hopkins) who loses his mind but leaves behind a historic work — or is it his?

“Saraband,” Ingmar Bergman’s return in his 80s to the same characters and actors (Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson) from his “Scenes from a Marriage” (1973).

“Schultze Gets the Blues,” with Horst Krause as a simple German accordion player who wins a contest and finds himself in New Orleans playing zydeco polka.

“Shopgirl,” the bittersweet relationship between a millionaire (Steve Martin) and a sales clerk (Claire Danes) who are divided not so much by age or money as by courage.

“Sin City,” the visual extravaganza adapted from Frank Miller’s dark graphic novels.

Noah Baumbach’s “The Squid and the Whale,” involves two divorcing writers (Jeff Daniels and Laura Linney), two sons with divided loyalties, and all the mysteries of parents and children.

“The Upside of Anger,” with housewife Joan Allen and retired baseball pitcher Kevin Costner building a relationship on booze and the wrong assumptions.

“Turtles Can Fly,” about children living amid the wreckage of war on the Iraqi-Turkish border.

“Walk the Line,” for its astonishing performances by Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon.

“The World,” Zhang Ke Jia’s revealing look at the culture of the workers in a Beijing theme park.

BEST DOCUMENTARIES

“Grizzly Man,” Werner Herzog’s portrait of a man who loves bears unwisely and too well.

“Aliens of the Deep,” James Cameron’s visual astonishment from the ocean floor.

“Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room,” mercilessly explaining how Enron fabricated the California energy crisis.

“Gunner Palace,” about the daily lives of American soldiers in Iraq.

“March of the Penguins,” about the responsibilities of parenthood.

“Murderball,” about the sport of full-contact quadriplegic wheelchair rugby (yes).

“No Direction Home: Bob Dylan,” Martin Scorsese’s look at the singer’s odyssey.

“Tell Them Who You Are,” Mark Wexler’s portrait of his complex and gifted father, the cinematographer Haskell Wexler.

“Touch the Sound,” about the deaf percussionist Evelyn Glennie.

“The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill,” about Mark Bittner, who knows San Francisco’s wild parrots by name.

BEST ANIMATED FILMS

“Wallace and Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit,” one of the most delightful films ever made.

“Tim Burton's Corpse Bride,” surprisingly cheerful under the circumstances.

“Robots,” with its jolly little children of Rube Goldberg in a future that looks like Fiestaware.

CANDIDATES FOR EBERT’S OVERLOOKED FILM FESTIVAL

“Off the Map,” Campbell Scott’s film with Joan Allen living in the New Mexico desert with her depressed husband (Sam Elliott) and imaginative daughter (Valentina de Angelis).

Gore Verbinski’s “The Weather Man,” with a brilliant Nicolas Cage as a man without a clue for his own happiness.

“Keane,” Lodge Kerrigan’s portrait of a schizophrenic (Damian Lewis) trying to hold himself together.

“Duma,” Carroll Ballard’s magnificent story of a boy and his cheetah.

“The Woodsman,” Nicole Kassell’s film starring Kevin Bacon as a recovering pedophile.