John Madden’s “Proof” is an extraordinary thriller about matters of scholarship and the heart, about the true authorship of a mathematical proof and the passions that coil around it. It is a rare movie that gets the tone of a university campus exactly right, and at the same time communicates so easily that you don’t need to know the slightest thing about math to understand it. Take it from me.

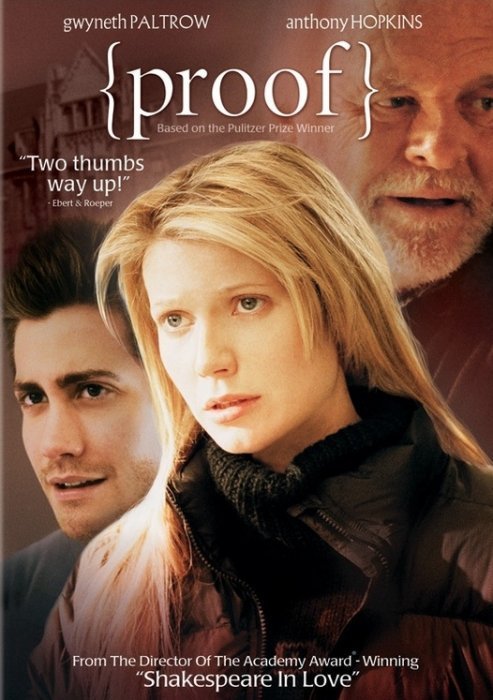

The film centers on two remarkable performances, by Gwyneth Paltrow and Hope Davis, as Catherine and Claire, the daughters of a mathematician so brilliant that his work transformed the field and has not yet been surpassed. But his work was done years ago, and at the age of 26 or 27, he began to “get sick,” is the way the family puts it. This man, named Robert and played by Anthony Hopkins, still has occasional moments of lucidity, but he lives mostly in delusion, filling up one notebook after another with meaningless scribbles. Yet he remains on the University of Chicago faculty, where he has already made a lifetime’s contribution; his presence and rare remissions are inspiring. Recently he had a year when he was “better.”

Catherine was a brilliant math student, too — at Northwestern, because she wanted to be free of her father. But she returned home to care for him when he got worse, and her life has been defined by her father and the family home. Hal (Jake Gyllenhaal), her father’s student and assistant, is hopelessly in love with her; she shies away from intimacy and suspects his motives. Most of the movie takes place after the father’s death (flashbacks show him in life and imagination), and Hal is going through the notebooks. “Hoping to find something of my dad’s you could publish?” Catherine asks him in a moment of anger.

Claire, the older sister, flies in from New York and makes immediate plans to sell the family home to the university: “They’ve been after it for years.” Catherine is outraged, but the movie subtly shows how Claire, not the brilliant sister, is the dominant one. There is the sinister possibility that she thinks (in all sincerity) that Catherine may have inherited the family illness, and should not be allowed to stay alone in Chicago. Claire expresses love and support for her sister, in terms that are frightening.

There is a locked drawer in Robert’s desk. Catherine gives Hal the key. It contains what may be a revolutionary advance on Robert’s earlier work; a new mathematical proof of incalculable importance. Did Robert somehow write this in a fleeing moment of clarity? The authorship of the proof brings into play all of the human dynamics that have been established, between Catherine and Claire and Hal, and indeed between all of them and the ghostly presence of the father.

“Proof,” based on the award-winning Broadway and London play by David Auburn, contains one scene after another that is pitch-perfect in its command of how academics talk and live. Having once spent a year as a University of Chicago doctoral candidate, I felt as if I were back on campus. There is a memorial service at which the speaker (Gary Houston) sounds precisely as such speakers sound; his subject is simultaneously the dead mathematician, and his sense of his own importance. There is a faculty party at which all of the right notes are sounded. And when Catherine and Hal speak, they talk as friends, lovers and fellow mathematicians; they communicate in several languages while speaking only one.

What makes the movie deep and urgent is that Catherine is motivated by conflicting desires. She wants to be a great mathematician, but does not want to hurt or shame her father. She wants to be a loyal daughter, and yet stand alone as herself. She half-believes her older sister’s persuasive smothering. She half-believes Hal loves her only for herself. At the bottom, she only half-believes in herself. That’s why the Paltrow performance is so fascinating: It’s essentially about a woman whose destiny is in her own hands, but she can’t make them close on it.

It would be natural to compare “Proof” with “A Beautiful Mind” (2001), another movie about a brilliant and mad mathematician. But they are miles apart. “A Beautiful Mind” tries to enter the world of the madman. “Proof” locates itself in the mind of the madman’s daughter, who loves him and sorrows for him, who has lived in his shadow so long she fears the light and the things that go with it.

Note: It doesn’t make the movie any better or worse, but it’s unique in that all of the locations match. There are no impossible journeys or non-existent freeway exits. The trip from Hyde Park to Evanston reflects the way you really do get there. So real do the locations feel that it’s a shock to find that most of the interiors were filmed in England; they match the movie’s Chicago locations seamlessly.