Sally Potter‘s “Yes” is a movie unlike any other I have seen or heard. Some critics have treated it as ill-behaved, as if its originality is offensive. Potter’s sin has been to make a movie that is artistically mannered and overtly political; how dare she write her dialogue in poetry, provide a dying communist aunt, and end the film in Cuba? And what to make of the housecleaner who sardonically comments on the human debris shed by her rich employers? The flakes of skin, the nail clippings, the wisps of dead hair, the invisible millions of parasites?

I celebrate these transgressions. “Yes” is alive and daring, not a rehearsal of safe material and styles. Sally Potter could easily have made a well-mannered love story with passion and pain at appropriate intervals, or perhaps, for Potter, that would not have been so easy, since all of her films strain impatiently at the barriers of convention. She sees no point in making movies that have been made before. See for example “Orlando,” in which Tilda Swinton plays a character who lives for centuries and trades genders.

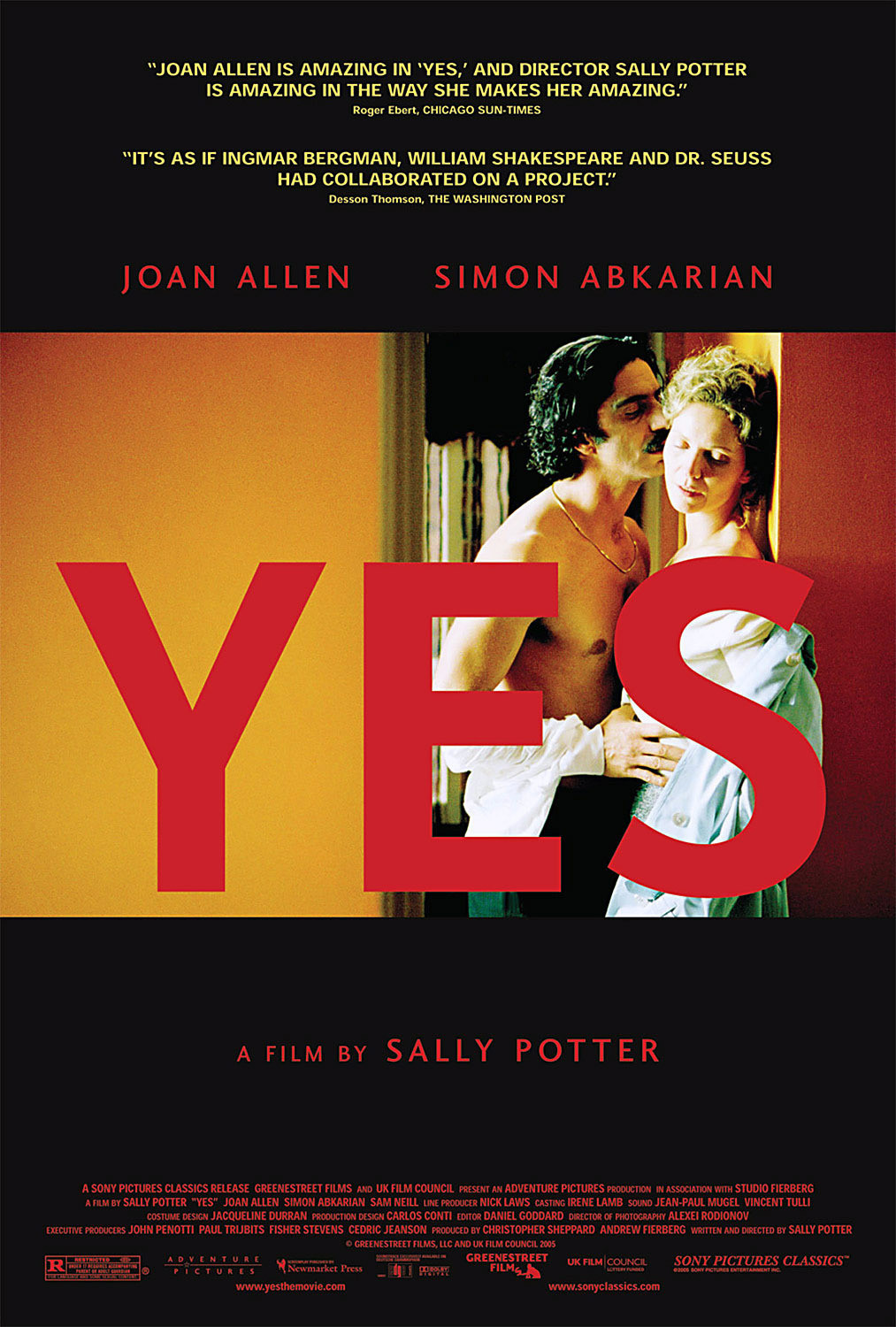

“Yes” is a movie about love, sex, class and religion, involving an elegant Irish-American woman (Joan Allen) and a Lebanese waiter and kitchen worker (Simon Abkarian). They are known only as She and He. “She” is a scientist, married lovelessly to a rich British politician (Sam Neill). “He” was a surgeon in Beirut, until he saved a man’s life only to see him immediately shot dead. Refusing to heal only those with the correct politics, he fled Lebanon and now uses his knives to chop parsley instead of repairing human hearts.

They meet at a formal dinner. They do it with their eyes. He smiles, she smiles. Neither turns away. An invitation has been offered and accepted. Their sex is eager and makes them laugh. They are not young; they are grateful because of long experience with what can go wrong.

There is a scene in the movie of delightful eroticism. It involves goings-on under the table in a restaurant. The camera regards not the details of this audacity, but the eyes and faces of the lovers. They take their time getting to where they are almost afraid to go. They look at each other, enjoying their secret, He looking for a reaction, She wary of revealing one. Her release is a barely subdued shudder of muffled ecstasy. This is what sex is about: Two people knowing each other, and using their knowledge. Compared to it, the sex scenes in most movies are calisthenics.

She was born in Belfast, raised in America, is Christian, probably Catholic. He is Arabic and Muslim. Both come from lands where people kill each other in the name of God. They are above all that. Or perhaps not. They have an economic imbalance: “You buy me with a credit card in a restaurant,” He says in a moment of anger. And: “Even to pronounce my name is an impossibility.” With his fellow kitchen workers he debates the way Western women display their bodies, the way their husbands allow them to be looked at by other men. He is worldly, understands the West, and yet his inherited beliefs about women are deeply ingrained, and available when he needs a vocabulary to express his resentment.

She, on the other hand, displays her body with a languorous healthy pride to him, and to us as we watch the movie. There is no explicit nudity. There is a scene where she goes swimming with her god-daughter, and we see that she is athletic, subtly muscled, with the neck and head of a goddess. To recline at the edge of the pool in casual physical perfection is as natural to She as it is disturbing to He. Their passion cools long enough for them to realize that they cannot live together successfully in either of their cultures.

Now, about the dialogue. It is written in iambic pentameter, the rhythm scheme of Shakespeare. It is a style poised between poetry and speech; “to be or not to be, that is the question,” and another question is, does that sound to you like poetry or prose? To me, it sounds like prose that has been given the elegance and discipline of formal structure. The characters never sound as if they’re reciting poetry, and the rhymes, far from sounding forced, sometimes can hardly be heard at all. What the dialogue brings to the film is a certain unstated gravity; it elevates what is being said into a realm of grace and care.

There is her dying aunt, an unrepentant Marxist who provides us her testament in an interior monologue while she is in a coma. This monologue, and others in the film, are heard while the visuals employ subtle, transient freeze-frames. The aunt concedes that communism has failed, but “what came in its place? A world of greed. A life spent longing for things you don’t need.” The same point is made by She’s housecleaner (Shirley Henderson) and other maids and lavatory attendants seen more briefly. They clean up after us. We move through life shedding a cloud of organic dust, while minute specks of life make their living by nibbling at us. These mites and viruses in their turn cast off their own debris, while elsewhere galaxies are dying; the universe lives by making a mess of itself.

Can She and He live together? Is there a way for their histories and cultures to coexist as comfortably as their genitals? The dying aunt makes She promise to visit Cuba. “I want my death to wake you up and clean you out,” she says. You and I know that Cuba has not worked, and I think the aunt knows it, too. But at least in Cuba the dead roots of her hopes might someday rise up and bear fruit. And Cuba has the advantage of being equally alien to both of them. Neither is an outsider when both are.

Sally Potter has said, “I think yes is the most beautiful and necessary word in the English language.” A statement less banal the more you consider it. Doesn’t it seem to you sometimes as if we are fighting our way through a thicket of no? When He and She first meet, their eyes say yes to sex. By the end of the film they are preparing to say yes to the bold overthrow of their lives up until then, and yes to the beginning of something hopeful and unknown.