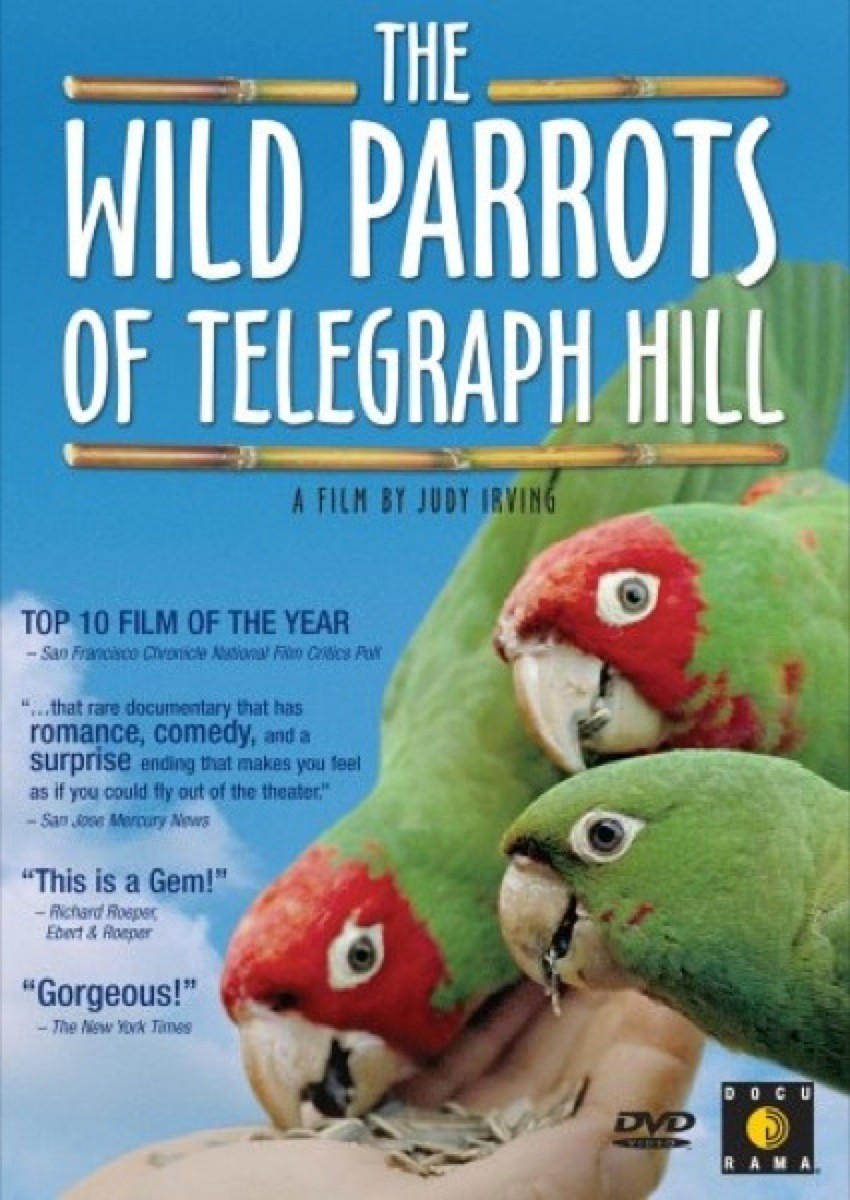

“The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill,” a documentary about Bittner and his birds by Judy Irving, is making its way around the country as an underground phenomenon, fueled by fans who urge their friends to see it. It is not the film you think it is going to be. You walk in expecting some kind of North Beach weirdo and his wild-eyed parrot theories, and you walk out still feeling a little melancholy over the plight of Connor, the only blue-crowned conure in a flock of red-crowned conures.

Connor had a mate, Bittner tells us, but the mate died. Now Connor hangs around with the other parrots but seems lonely and depressed, a blue-crowned widower who can sometimes get nasty with the other birds, but comes to the defense of weak or sick birds when the flock picks on them. Picasso and Sophie, both red-crowned parrots, are a couple until Picasso disappears; Bittner begins to hope that maybe Connor and Sophie will start to date and produce some purple-headed babies.

Nobody knows how the parrots, all born in the wild and imported from South America, escaped captivity, found each other and started their flock. Irving has several North Beach residents recite the usual urban legends (they were released by an eccentric old lady, a bird truck overturned, etc). No matter. They live and thrive.

You would think it might get too cold in the winter for these tropical birds, but no: They can withstand cold fairly well, and the big problem for them is getting enough to eat. Indeed, flocks of wild parrots and parakeets exist in colder climates; the famous colony of parakeets in Chicago’s Hyde Park was evicted from home of their nests only a week ago, after 15 or 20 years, because they were interfering with utility lines. Oddly, most bird-lovers seem to resent trespassers such as wild parrots, on the grounds that they are outside their native range. That they are here through no fault of their own, that they survive and thrive and are intelligent and beautiful birds, is enough for Mark Bittner, and by the end of the film that’s enough for us, too.

He gives us brief biographies of some of the birds. Sometimes he takes them into his home when they’re sick or injured, but after they recover they all want to return to the wild — except for Mingus, who keeps trying to get back into the house. Their biggest enemies are viruses and hawks. The flock always has a hawk lookout posted, and has devised other hawk-avoidance tactics, of which the most ingenious is to fly behind a hawk, which can attack only straight ahead and has a wider turning-radius than parrots.

Bittner originally came to San Francisco, he tells us, seeking work as a singer. That didn’t work out. He lived on the streets, did odd jobs, read a lot, met some of the original hippies (Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Gary Snider). For the three years before the film begins, he has lived rent-free in a cottage below the house of a wealthy couple who live near the parrots on Telegraph Hill. Now he is about to be homeless again, while the cottage is renovated into an expensive rental property. The parrots are threatened with homelessness, too, and Bittner testifies on their behalf before the city council. San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsome vows nothing bad will happen to the parrots; would that we had such statesmen in Illinois.

As Bittner tends and feeds his flock, visitors to the wooded area on Telegraph Hill want to categorize him. Is he a scientist? Paid by the city? What’s his story? His story is, he finds the parrots fascinating and lovable. He quotes Gary Snider: “If you want to study nature, start right where you are.” Can he live like this forever? He is about 50, in good health, with a long red ponytail. He says he decided not to cut his hair until he gets a girlfriend. Whether either Connor the blue-crowned conure or Bittner the red-headed birdman finds a girlfriend, I will leave for you to discover.