Terrence Malick’s “The New World” strips away all the fancy and lore from the story of Pocahontas and her tribe and the English settlers at Jamestown, and imagines how new and strange these people must have seemed to one another. If the Indians stared in disbelief at the English ships, the English were no less awed by the somber beauty of the new land and its people. They called the Indians “the naturals,” little understanding how well the term applied.

Malick strives throughout his film to imagine how the two civilizations met and began to speak when they were utterly unknown to one another. We know with four centuries of hindsight all the sad aftermath, but it is crucial to “The New World” that it does not know what history holds. These people regard one another in complete novelty, and at times with a certain humility imposed by nature. The Indians live because they submit to the realities of their land, and the English nearly die because they are ignorant and arrogant.

Like his films “Days of Heaven” and “The Thin Red Line,” Malick’s “The New World” places nature in the foreground, instead of using it as a picturesque backdrop as other stories might. He uses voice-over narration by the principal characters to tell the story from their individual points of view. We hear Capt. John Smith describe Pocahontas: “She exceeded the others not only in beauty and proportion, but in wit and spirit, too.” And later the settler John Rolfe recalls his first meeting: “When first I saw her, she was regarded as someone broken, lost.”

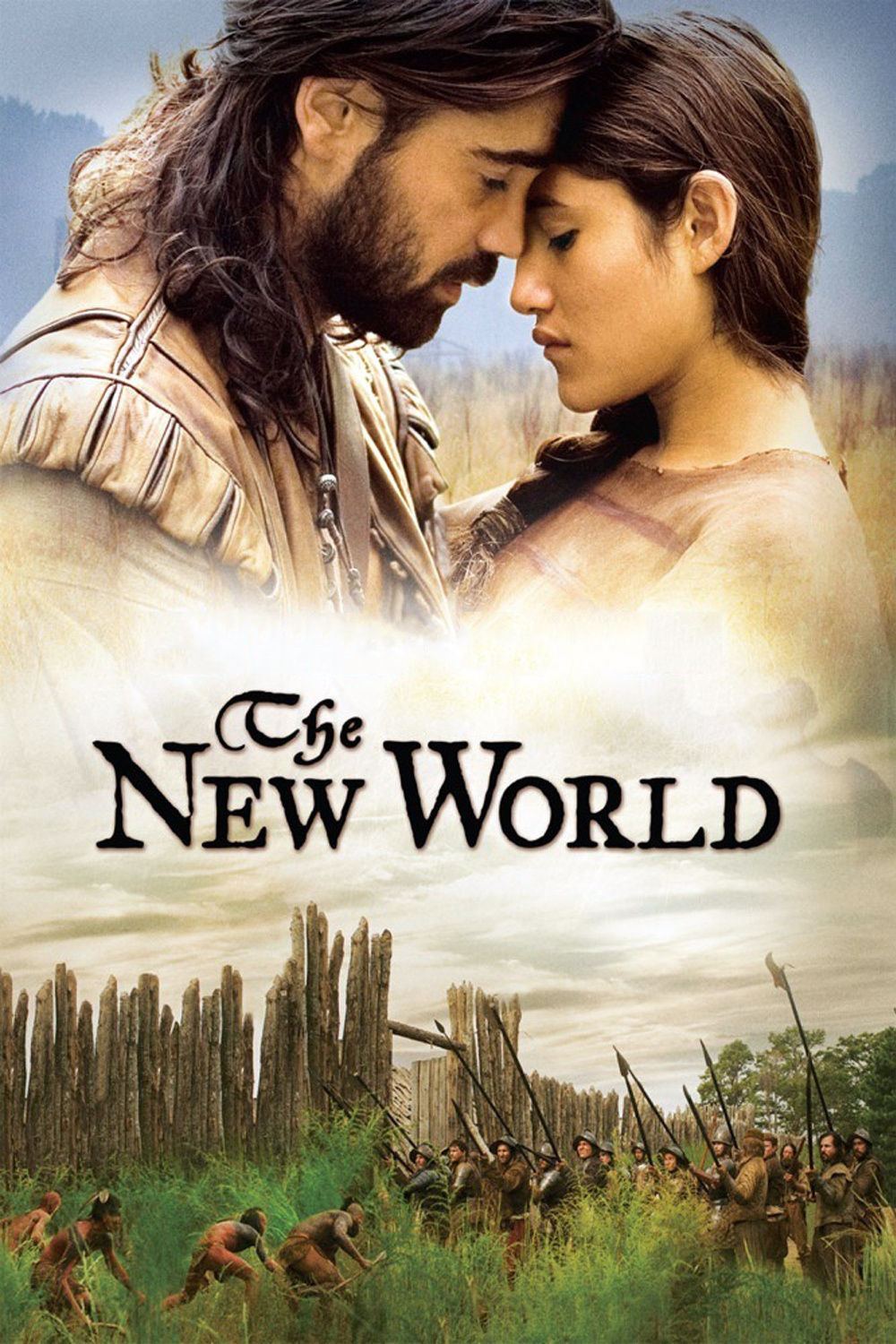

“The New World” is Pocahontas’ story, although the movie deliberately never calls her by any name. She is the bridge between the two peoples. Played by a 14-year-old actress named Q'orianka Kilcher as a tall, grave, inquisitive young woman, she does not “fall in love” with John Smith, as the children’s books tell it, but saves his life — throwing herself on his body when he is about to be killed on the order of her father the chief — for far more complex reasons. The movie implies, rather than says, that she is driven by curiosity about these strange visitors, and empathy with their plight as strangers, and with admiration for Smith’s reckless and intrepid courage. If love later plays a role, it is not modern romantic love so much as a pure instinctive version.

And what of Smith (Colin Farrell)? To see him is to know he knows the fleshpots of London and has been raised without regard for women. He is a troublemaker, under sentence of death by the expedition leader, Capt. Newport (Christopher Plummer) for mutinous grumblings. Yet when he first sees Pocahontas, she teaches him new feelings by her dignity and strangeness. There is a scene where Pocahontas and Smith teach each other simple words in their own languages, words for sky, eyes, lips, and the scene could seem contrived but it doesn’t, because they play it with such a tender feeling of discovery.

Smith is not fair with Pocahontas. Perhaps you know the story, but if you don’t, I’ll let the movie fill in the details. She later encounters the settler John Rolfe (Christian Bale), and from him finds loyalty and honesty. Her father, the old chief Powhatan (August Schellenberg), would have her killed for her transgressions, but “I cannot give you up to die. I am too old for it.” Abandoned by her tribe, she is forced to live with the English. Rolfe returns with her to England, where she meets the king and is a London sensation, although that story, too, is well-known.

There is a meeting that she has in England, however, that Malick handles with almost trembling tact, in which she deals with a truth hidden from her, and addresses it with unwavering honesty. What Malick focuses on is her feelings as a person who might as well have been transported to another planet. Wearing strange clothes, speaking a strange language, she can depend only on those few she trusts, and on her idea of herself.

The are two new worlds in this film, the one the English discover, and the one Pocahontas discovers. Both discoveries center on the word “new,” and what distinguishes Malick’s film is how firmly he refuses to know more than he should in Virginia in 1607 or London a few years later. The events in his film, including the tragic battles between the Indians and the settlers, seem to be happening for the first time. No one here has read a history book from the future.

There are the familiar stories of the Indians helping the English survive the first winter, of how they teach the lore of planting corn and laying up stores for the winter. We are surprised to see how makeshift and vulnerable the English forts are, how evolved the Indian culture is, how these two civilizations could have built something new together — but could not, because what both societies knew at that time did not permit it. Pocahontas could have brought them together. In a small way, she did. She was given the gift of sensing the whole picture, and that is what Malick founds his film on, not tawdry stories of love and adventure. He is a visionary, and this story requires one.

This review is based on a viewing of the re-edited version of “The New World,” which runs about 130 minutes; I also saw the original 150-minute version and noticed no startling changes.