Then in 1968, I saw “Don't Look Back” (1967), D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary about Dylan’s 1965 tour of Great Britain. In my review, I called the movie “a fascinating exercise in self-revelation,” and added: “The portrait that emerges is not a pretty one.” Dylan is seen not as a “lone, ethical figure standing up against the phonies,” I wrote, but is “immature, petty, vindictive, lacking a sense of humor, overly impressed with his own importance and not very bright.”

I felt betrayed. In “Don’t Look Back,” he mercilessly puts down a student journalist, and is rude to journalists, hotel managers, fans. Although Joan Baez was the first to call him on her stage when he was unknown, after she joins the tour, he does not ask her to sing with him. Eventually she bails out and goes home.

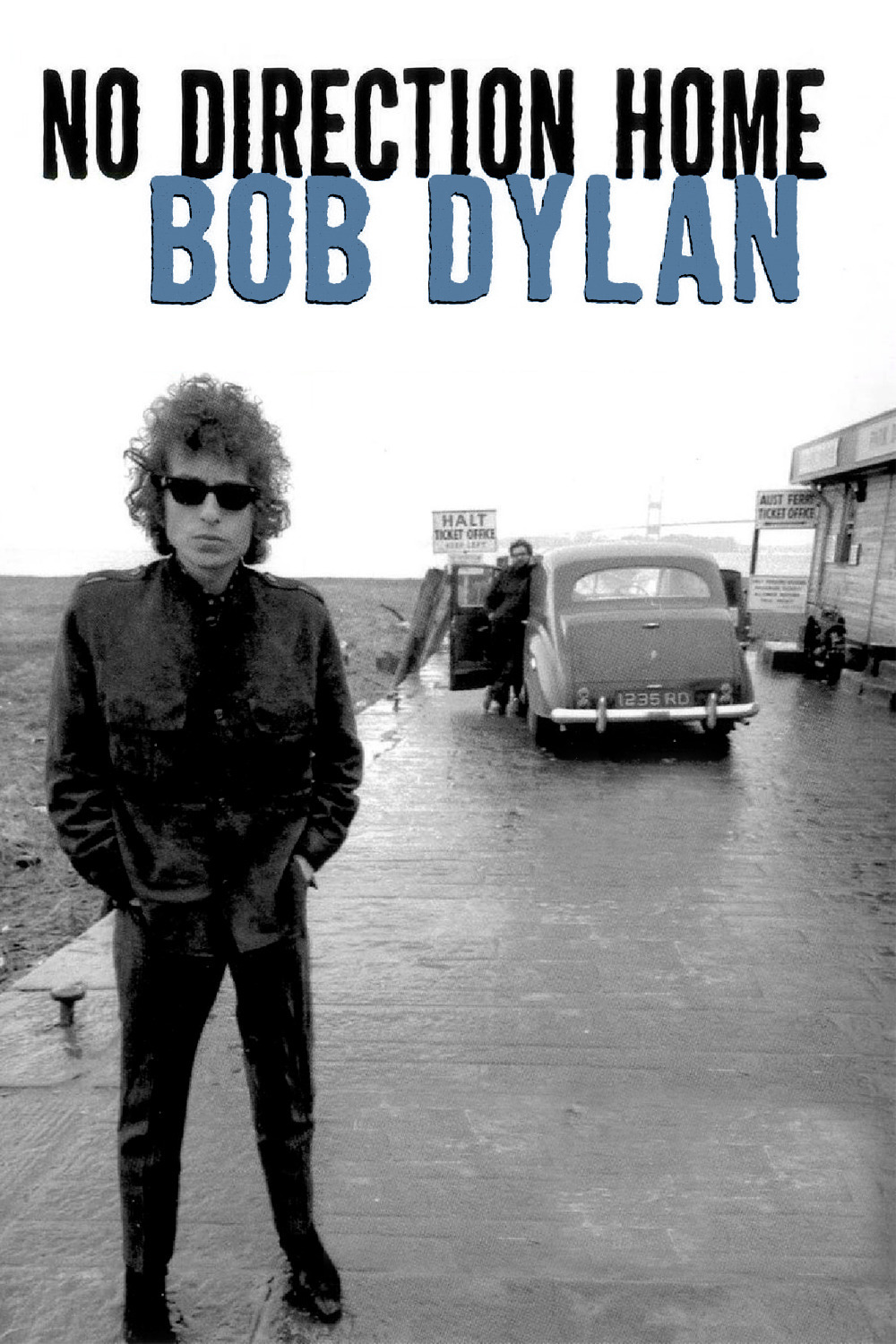

The film fixed my ideas about Dylan for years. Now Scorsese’s “No Direction Home: Bob Dylan,” a 225-minute documentary that will play in two parts Sept. 26-27 on PBS (and comes out today on DVD), creates a portrait that is deep, sympathetic, perceptive and yet finally leaves Dylan shrouded in mystery, which is where he properly lives.

The movie uses revealing interviews made recently by Dylan, but its subject matter is essentially the years between 1960, when he first came into view, and 1966, when after the British tour and a motorcycle accident, he didn’t tour for eight years. He was born in 1941, and the career that made him an icon essentially happened between his 20th and 25th years. He was a young man from a Minnesota town who had the mantle of a generation placed, against his will, upon his shoulders. He wasn’t at Woodstock; Arlo Guthrie was.

Early footage of his childhood is typical of many Midwestern childhoods: the town of Hibbing, Minn., the homecoming parade, bands playing at dances, the kid listening to the radio and records. The early sounds he loved ran all the way from Hank Williams and Webb Pierce to Muddy Waters, the Carter Family and even Bobby Vee, a rock star so minor that young Robert Zimmerman for a time claimed to be Bobby Vee.

He hitched a ride to New York (or maybe he didn’t hitch; his early biography is filled with romantic claims, such as that he grew up in Gallup, N.M.). In Greenwich Village, he found the folk scene, and it found him. He sang songs by Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and others, and then was writing his own. He caught the eye of Baez, and she mentored and promoted him. Within a year he was … Dylan.

The movie has a wealth of interviews with people who knew him at the time: Baez, Pete Seeger, Mike Seeger, Liam Clancy, Dave Von Ronk, Maria Muldaur, Peter Yarrow and promoters like Harold Leventhal. There is significantly no mention of Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. The documentary “The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack” (2000) claims it was Elliott who introduced Dylan to Woody Guthrie, and suggested that he use a harmonica holder around his neck, and essentially defined his stage persona; “There wouldn’t be no Bob Dylan without Ramblin’ Jack,” says Arlo Guthrie, who is also not in the Scorsese film.

Dylan’s new friends in music all admired the art but were ambivalent about the artist. Van Ronk smiles now about the way Dylan “borrowed” his “House of the Rising Sun.” The Beat Generation, especially Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, influenced Dylan, and there are many observations by the beat poet Allen Ginsberg, who says he came back from India, heard a Dylan album and wept, because he knew the torch had been passed to a new generation.

It is Ginsberg who says the single most perceptive thing in the film: For him, Dylan stood atop a column of air. His songs and his ideas rose up from within him and emerged uncluttered and pure, as if his mind, soul, body and talent were all one.

Dylan was embraced by the left-wing musical community of the day. His “Blowin’ in the Wind” became an anthem of the civil rights movement. His “Only a Pawn in the Game” saw the killer of Medgar Evers as an insignificant cog in the machine of racism. Baez, Seeger, the Staple Singers, Odetta, Peter, Paul and Mary all sang his songs and considered him a fellow warrior.

But Dylan would not be pushed or enlisted, and the crucial passages in this film show him drawing away from any attempt to define him. At the moment when he was being called the voice of his generation, he drew away from “movement” songs. A song like “Mr. Tambourine Man” was a slap in the face to his admirers, because it moved outside ideology.

Baez, interviewed before a fireplace in the kitchen of her home, still with the same beautiful face and voice, is the one who felt most betrayed: Dylan broke her heart. His change is charted through the Newport Folk Festival: early triumph, the summit in 1964 when Johnny Cash gave him his guitar, the beginning of the end with the electric set in 1965. He was backed by Michael Bloomfield and the Butterfield Blues Band in a folk-rock-blues hybrid that his fans hated. When he took the new sound on tour the Hawks (later the Band), audiences wanted the “protest songs,” and shouted “Judas!” and “What happened to Woody Guthrie?” when he came onstage. Night after night, he opened with an acoustic set that was applauded, and then came back with the band and was booed.

“Dylan made it pretty clear he didn’t want to do all that other stuff,” Baez says, talking of political songs, “but I did.” It was the beginning of the Vietnam era, and Dylan had withdrawn. When he didn’t ask Baez onstage to sing with him on the British tour, she says quietly, “It hurt.”

But what was happening inside Dylan? Was he the jerk portrayed in “Don’t Look Back”? Scorsese looks more deeply. He shows countless news conferences where Dylan is assigned leadership of his generation and assaulted with inane questions about his role, message and philosophy. A photographer asks him, “Suck your glasses” for a picture. He is asked how many protest singers he thinks there are: “There are 136.”

At the 1965 Newport festival, Pete Seeger recalls, “The band was so loud, you couldn’t understand one word. I kept shouting, ‘Get that distortion out! If I had an ax, I’d chop the mike cable right now!’ ” For Seeger, it was always about the words and the message. For Dylan, it was about the words and then it became about the words and the music, and it was never particularly about the message.

Were drugs involved in these years? The movie makes not the slightest mention of them, except obliquely in a scene where Dylan and Johnny Cash do a private duet of “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” and it’s clear they’re both stoned. There is sad footage near the end of the British tour, when Dylan says he is so exhausted: “I shouldn’t be singing tonight.”

The archival footage comes from many sources, including documentaries by Pennebaker and Murray Lerner (“Festival“). Many of the interviews were conducted by Michael Borofsky, and Jeff Rosen was a key contributor. But Scorsese provides the master vision, and his factual footage unfolds with the narrative power of fiction.

What it comes down to, I think, is that Robert Zimmerman from Hibbing, Minn., who mentions his father only because he bought the house where Bobby found a guitar, and mentions no other member of his family at all, who felt he was from nowhere, became the focus for a time of fundamental change in music and politics. His songs led that change, but they transcended it. His audience was uneasy with transcendence. They kept trying to draw him back down into categories. He sang and sang, and finally, still a very young man, found himself a hero who was booed. “Isn’t it something, how they still buy up all the tickets?” he asks about a sold-out audience that hated his new music.

What I feel for Dylan now and did not feel before is empathy. His music stands and it will survive. Because it embodied our feelings, we wanted him to embody them, too. He had his own feelings. He did not want to embody ours. We found it hard to forgive him for that. He had the choice of caving in or dropping out. The blues band music, however good it really was, functioned also to announce the end of his days as a standard-bearer. Then after his motorcycle crash in 1966, he went away into a personal space where he remains.

Watching him singing in “No Direction Home,” we see no glimpse of humor, no attempt to entertain. He uses a flat, merciless delivery, more relentless cadence than melody, almost preaching. But sometimes at the press conferences, we see moments of a shy, funny, playful kid inside. And just once, in his recent interviews, seen in profile against a background of black, we see the ghost of a smile.