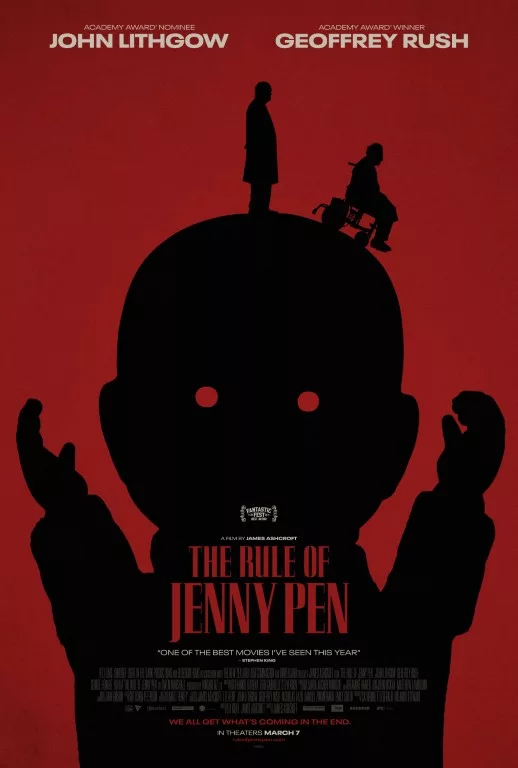

Usually, horror movies that exploit elderly actors for shock value are about women. In every way but that one, “The Rule of Jenny Pen” is a hagsploitation picture—even the title, with a few small tweaks, could qualify. (On an alternate timeline, “Who Rules, Jenny Pen?,” starring Shelley Winters and Tallulah Bankhead, is a classic of the subgenre.) The film stars two well-known thespians in their golden years, John Lithgow (born 1945) and Geoffrey Rush (born 1951), in melodramatic roles that highlight the grotesque horror of the aging process. Lithgow even prances around singing a children’s song, which is terrifying because he’s old.

This is all in good fun, of course. At the same time, “Jenny Pen” deals with some very serious (some might even say traumatic) subjects, sticking its finger into the open wounds of medical gaslighting, elder abuse, and sexual abuse—both of children and of elderly women—and wiggling it around a little. Combined with the handsome cinematography and artful direction, the effect is very Ari Aster, especially when an old man randomly burns to death at the beginning of the film.

Aster is contemporary cinema’s greatest troll, and “Jenny Pen” director James Ashcroft is going for something similarly mischievous here. And when “Jenny Pen” locks in, it succeeds, which is to say that it glues you to your seat and makes you want to leave the theater (or shut it off, if you’re watching on Shudder) at the same time. Too often, however, Ashcroft crudely shifts between black comedy and disturbing violence, rather than accomplishing the more difficult task of combining the two into one nauseating, yet undeniably thrilling sensation.

Like Joan Crawford and Bette Davis in “What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?,” Lithgow and Rush are a mismatched pair of unpleasant personalities. Stefan (Rush) is a respected (and seemingly friendless) New Zealand judge who’s confined to a wheelchair after suffering a stroke in the opening scene. (He’s in court delivering the sentence on a child abuse case, because “Jenny Pen” always defaults to upsetting.) Stefan is also a condescending dickhead, rude to his roommate at the nursing home (George Henare) and contemptuous of the mostly female care staff. Dave (Lithgow), meanwhile, is the Baby Jane of the piece, kooky and demented and more dangerous than he looks.

Longtime resident Dave has turned Royale Pine Mews into his personal fiefdom, terrorizing his compatriots every night after lights out and manipulating the staff into enforcing his will. Refuse to bend the knee and lick the titular doll’s asshole—no, really; that’s the phrasing used, and the physical act demanded, in the movie—and you might find yourself “dying in your sleep.” The scenes where Dave tortures his fellow residents are alarming, as sadistic displays of dominance over helpless people ought to be. Where it gets weird is when shots of those same minor characters, many of whom are in various stages of dementia, are played for laughs later on.

Is this a nightmare, or a joke? For most of its runtime, “Jenny Pen” plays like a nightmare, as Stefan’s dilemma deepens and his body deteriorates in turn. By the end of the movie, he’s barely able to keep food in his mouth, and again the void between sympathizing with this character—he’s also a jerk, remember—and reveling in his suffering is incredibly loud. So it goes that Lithgow and Rush end up in a cartoonish physical confrontation towards the end of the movie, the camera placed inches from their noses for maximum carnivalesque effect.

A big part of “Jenny Pen’s” appeal is in Lithgow’s casting. Everybody loves when this mild-mannered man acts totally over-the-top evil, and Lithgow obliges in pants pulled up to his chest and a creepy baby-doll puppet on one hand. His New Zealand accent isn’t terribly convincing, however, and there are times when he honestly could go bigger, given the type of movie that this is. Or is this that type of movie—you know, a campy, unserious one?

The obsession with pee suggests that it is. The pathos of Henare’s character, a Maori retired footballer, trying and failing to perform a haka in the rest-home cafeteria suggests that it isn’t. Combining these modes is very much possible, and “Jenny Pen” finds the balance often enough that the joke does ultimately land. It could hit harder, however, were its impact not diluted by the overly long runtime and uneven tone. For a movie that undercuts itself for its own amusement, however, intermittently successful is pretty good.