The 12-year-old boy helped raise the cheetah, after he and his father found it as a cub. The boy, named Xan, lives on a farm in South Africa, where he and Duma form a strong bond, but their friendship cannot last forever. An emergency forces the family to move to the city, and Xan realizes that Duma, now fully grown, should be returned to the wild.

There might be reasonable ways of doing that. Perhaps Xan (Alex Michaeletos) could call the animal welfare people. Instead, without telling his mother (Hope Davis), he decides to personally return Duma to the wilderness. There is a scene of the cheetah riding in the sidecar of an old motorcycle, which Xan drives into the desert. It could be a cute scene, maybe funny, in a different kind of movie, but “Duma” takes itself seriously, and is not a cute children’s story but a grand tale of adventure.

Xan has courage but not a lot of common sense. He is headed into the Kalahari Desert, where to get lost is, usually, to die. Of course the motorcycle runs out of gas. Then he meets another wanderer in the desert, named Ripkuna (Eamonn Walker), who once worked in the mines of Johannesburg but now prefers to work alone, perhaps for reasons we would rather not know. He warns Xan of the dangers ahead (“That is a place of many teeth, my friend; that is a place to die”). He has the knowledge to save the boy and the cheetah. But what is his agenda?

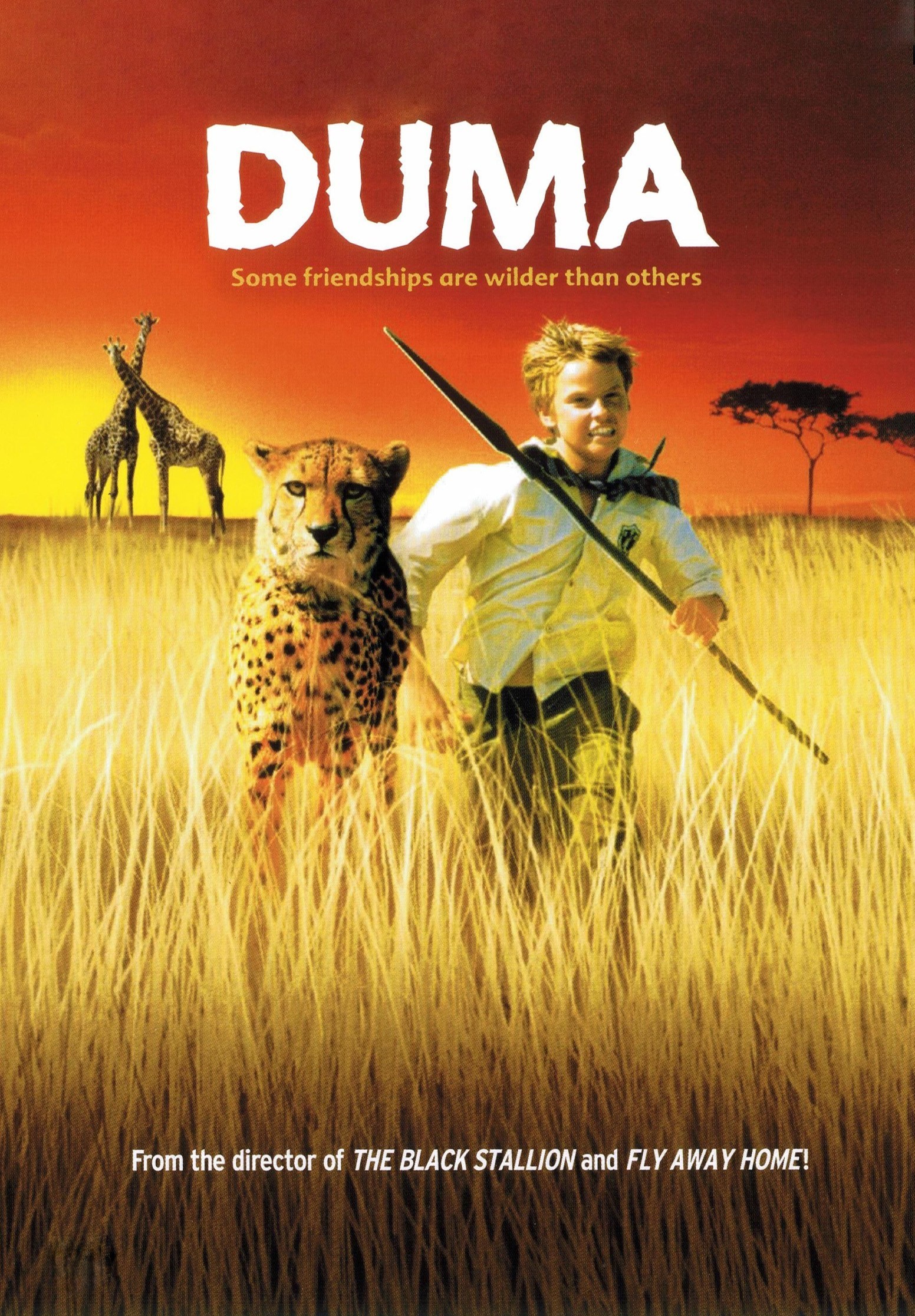

“Duma” is an astonishing film by Carroll Ballard, the director who is fascinated by the relationship between humans, animals and the wilderness. He works infrequently, but unforgettably. Perhaps you have seen his “The Black Stallion” (1979), about a boy and a horse who are shipwrecked, and begin a friendship that leads to a crucial horse race. Or his “Never Cry Wolf” (1983), based on the Farley Mowat book about a man who goes to live in the wild with wolves. Or the wonderful “Fly Away Home” (1996), about a 13-year-old girl who solos in an ultralight aircraft, leading a flock of pet geese south from Canada.

The wolf and geese stories were, incredibly, based on fact. So, perhaps even more incredibly, is “Duma.” There really was a boy and a cheetah, written about in the book How It Was With Dooms, by Xan Hopcraft and his mother, Carol Cawthra Hopcraft. Even more to the point: This movie shows a real boy and a real cheetah (actually, four cheetahs were used). There are no special effects. The cheetah is not digitized. What we see on the screen is what is happening, and that lends the film an eerie intensity. Animals are fascinating when they are free to be themselves; when they are manipulated by CGI into cute little actors who behave on cue, what’s the point?

How is this film possible? There are shots showing a desert empty to the horizon, except for the boy and the cheetah. No doubt handlers are right there out of camera range, ready to act in an emergency, but it is clear the filmmakers and the boy trust the animals they are working with.

True, cheetahs are a special kind of big cat; Wikipedia informs us, “Because cheetahs are far less aggressive than other big cats, cubs are sometimes sold as pets.” Yes, but a pet that can, as Xan tells his dad (Campbell Scott) “outrun your Porsche.” A pet that is a carnivore. It would seem that Duma can be trusted, but as W. G. Sebald once observed, “Men and animals regard each other across a gulf of mutual incomprehension.”

And if Duma can be trusted, can the African man, Ripkuna? Where is he leading them? He must know that a reward has been posted for the missing boy, and that a tame cheetah can be sold for a good amount of money. While these questions circle uneasily in our minds, “Duma” creates scenes of wonderful adventure. The stalled motorcycle is turned into a wind-driven land yacht. A raft trip on a river involves rapids and crocodiles. The cheetah itself plays a role in their survival. And the movie takes on an additional depth because Xan is not a cute one-dimensional “family movie” child, and Ripkuna is freed from the usual cliches about noble and helpful wanderers. These are characters free to hold surprises in the real world.

Watching this movie, absorbed by its storytelling, touched by its beauty, fascinated by the bond between the boy and the animal, I was also astonished by something else: The studio does not know if it is commercial! The most dismal stupidities can be inflicted on young audiences, but let a family movie come along that is ambitious and visionary, and distributors lose confidence. It’s as if they fear some movies are better than the audience can handle.

“Duma” has had test runs in the Southwest. Now it opens in Chicago, and the box office performance here will decide its fate. That is not a reason to see it. Moviegoers do not buy tickets to “support” a movie, nor should they. The reason to see “Duma” is that it’s an extraordinary film, and intelligent younger viewers in particular may be enthralled by it.