They meet by accident in the supermarket. It’s been — how many years? They were in love once. They were a couple. They were “Damian and Diana” to everyone who knew them. Now they’re both married to others. She’s pregnant. They smile and exchange meaningless commonplaces. They separate. Each of their carts is filled with items for the use of a person the other will never meet.

In another aisle, they meet again. Not by accident. There is more to be said, but not very much that can be safely said without an enormous upheaval in their lives. It is clear to us, perhaps to them, that they should never have broken up. No matter what has happened, no matter who they married, he says, “we’re Damian and Diana.” That will never change.

Thank God “Nine Lives” is an episodic film, so everything they have to say or do has to be contained in about 12 minutes. To know why they broke up or to see them get back together would involve us in a full-length love story of the sort we are familiar with.

It might be a good one. But here, in this meeting that is seen in one unbroken shot in a supermarket, we see the crucial heart of their relationship. It is based on the truth that their lives have moved on. Perhaps they should have stayed together. But they didn’t. It’s not important to know whether they start seeing each other again. But it is important for them to know that they want to, because to live without that knowledge is to dishonor their real feelings.

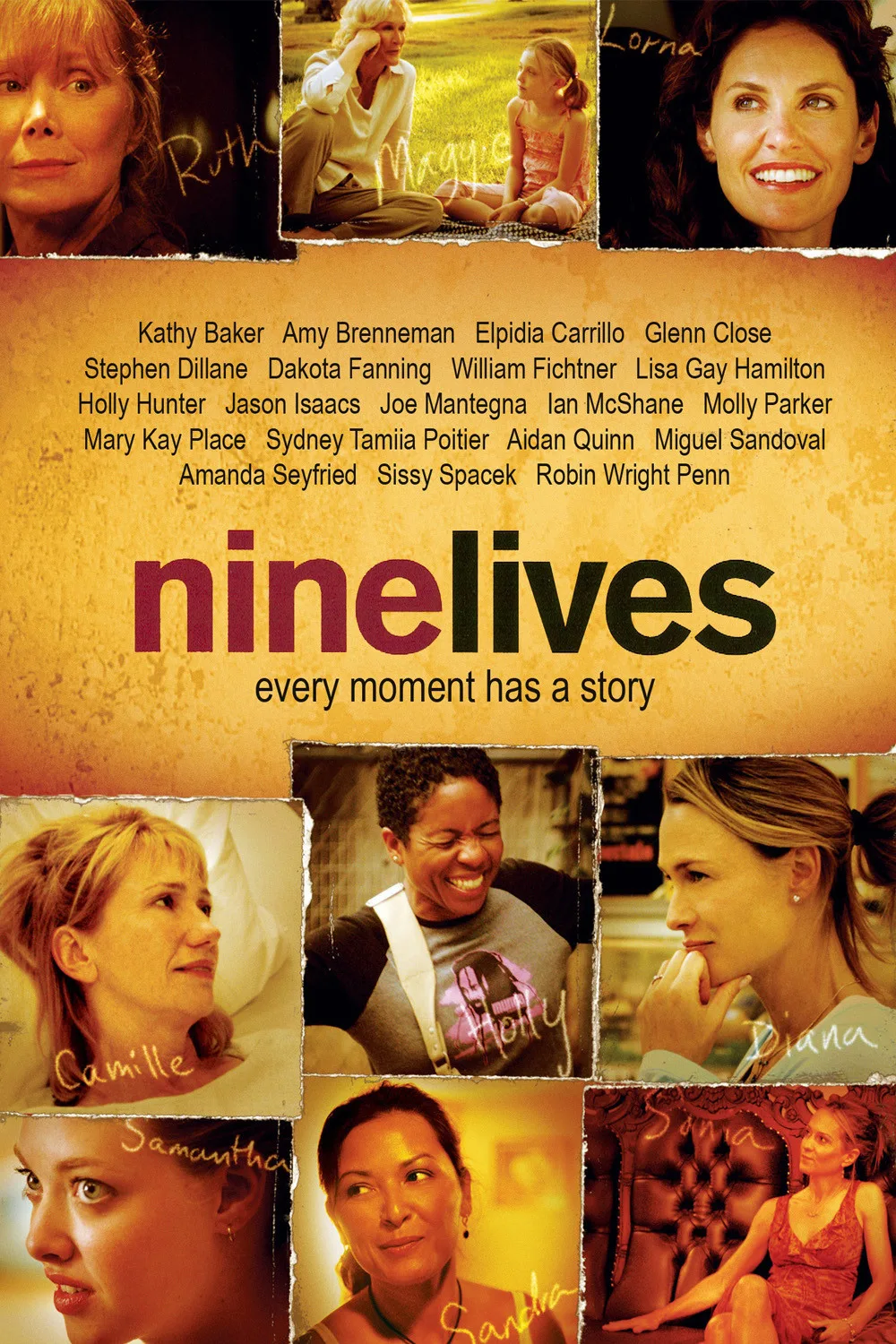

This little story, starring Robin Wright Penn and Jason Isaacs, is told in “Nine Lives,” a collection of nine vignettes written and directed by Rodrigo Garcia. Each one contains a moment of truth, each one is about the same length, each one is told in a single shot, although the camera work isn’t showy.

Sometimes the episodes seem obvious at first. Kathy Baker plays a woman who will undergo breast surgery in a few hours. In her hospital bed, she is frightened and angry; she’s short-tempered with the nurses, and hard on her husband (Joe Mantegna). A nurse adds a sedative to her IV drip, and she grows calmer and then — well, happy. She sees the good in things. The sedative has done its work.

But the episode is about so much more than that. It is about the indignity of surgeons inserting knives into your unconscious body, and about the fear of loss, and the impersonality of hospitals but the humanity of nurses, and the patience and love of her husband. Was she acting bitchy? When you’re about to get a breast removed, you’re not going for a good grade in deportment. Sometimes we behave badly for the best reasons in the world, and this movie knows that.

Other scenes. There is a prisoner (Elpidia Carrillo), who gets crazy because this is visitor’s day and her daughter is on the other side of the glass, and the telephone doesn’t work. An angry daughter (Lisa Gay Hamilton), who returns after a long absence to the home where she was raised and abused. This woman, so wounded, so borderline, is the same woman who, we discover in the hospital scene, is the nurse who is gentle and cares. Sissy Spacek plays a despairing mother in a dysfunctional household in one segment, and turns up in another prepared, perhaps, to have a forbidden night in a motel with Aidan Quinn. Glenn Close and Dakota Fanning visit a cemetery together in the last story, where the final shot will blindside you.

There is notoriously not a market for short films. You can’t book them or advertise them, it’s impossible to try to review them (and besides, where can the readers see them?). But short films are a form with purpose, just as short stories are. Some stories need only introduce us to a character or two and spend enough time with them for us to discover something about their natures, and perhaps our natures. The greatest short story writers, like William Trevor and Alice Munro, can awe us; their stories are short but not small.

Here Rodrigo Garcia does the same thing. The son of the novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez, he has the same love for his characters, and although his stories are all (except for one) realistic, he shares his father’s appreciation for the ways lives interweave and we touch each other even if we are strangers. A movie like this, with the appearance of new characters and situations, focuses us; we watch more intently, because it is important what happens. These characters aren’t going to get bailed out with 110 minutes of plot. Their lives have reached a turning point here and now, and what they do must be done here and now, or forever go unknown.