I have known Haskell Wexler for 36 years. When Haskell had a rough cut of “Medium Cool,” his docudrama shot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, he asked me to see it after Paramount got cold feet about distribution. Like many people since then, I thought it was a powerful and courageous film; I showed it at my Overlooked Film Festival two years ago. Haskell and I became friends over the years. I remember swimming off Jamaica with Haskell and his wife, the actress Rita Taggart. I remember going through “Blaze” a frame at a time with Haskell at the Hawaii Film Festival, and taking apart “Casablanca” with him on Dusty Cohl’s Floating Film Festival.

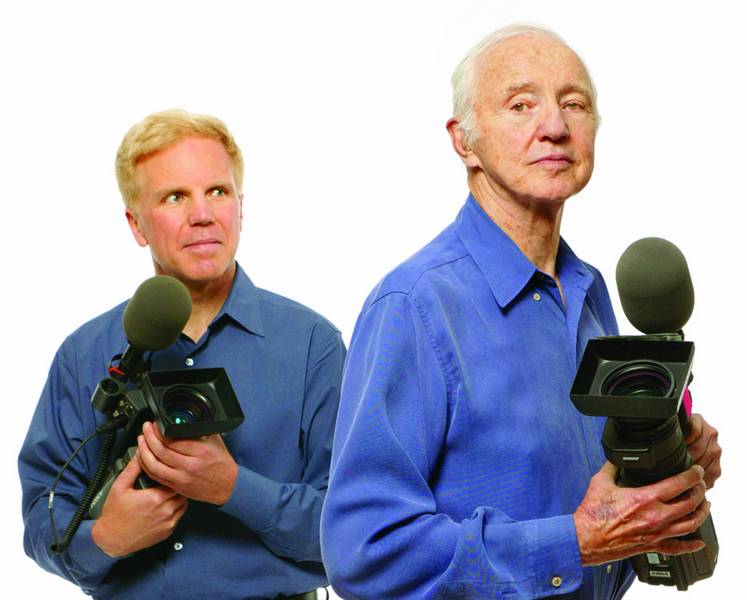

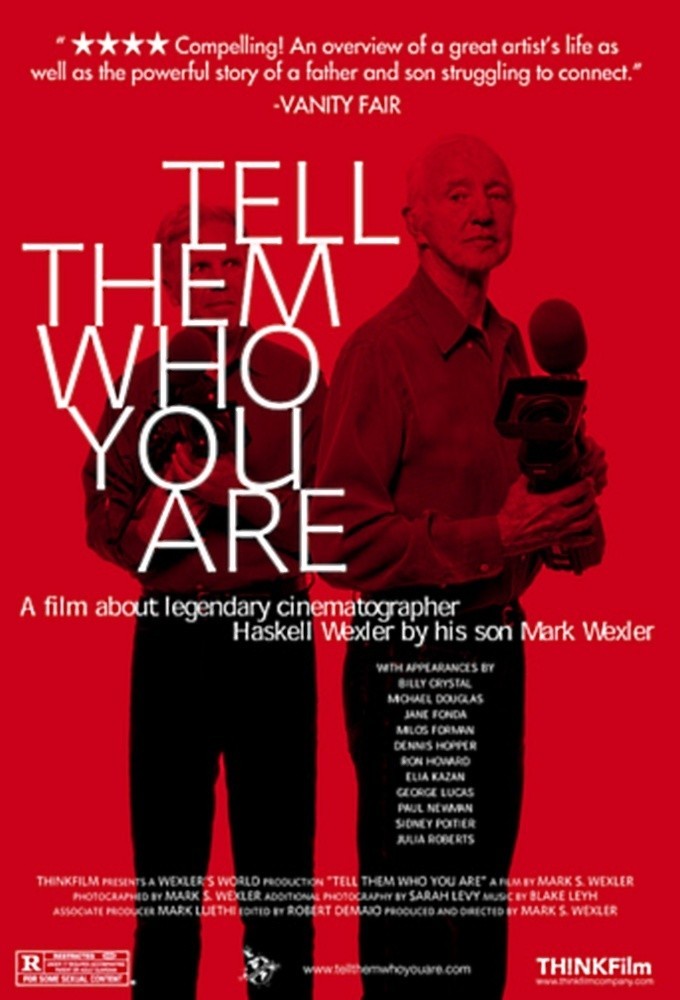

So he is a friend. He is also a great cinematographer. And he is an activist for progressive causes, a sometime director of features and docmentaries, and the subject of a new documentary named “Tell Them Who You Are.” The documentary is by his son, Mark, who tells his father very clearly: “I’m not a fan. I’m a son.” Mark made a previous doc, “Me and My Matchmaker,” which I found fascinating; he meets a matchmaker, thinks it would be interesting to watch her at work, asks her to find him a wife, and gets involved in a process neither he nor the matchmaker could possibly have anticipated.

Mark’s new doc is frankly intended, we learn, as an attempt to get to know his father better. The child of Haskell’s second marriage, he has an almost oedipal rivalry that has, among other things, led him to politics that are the opposite of his father’s.

Haskell, now in his 80s, agreed to participate with misgivings, and is not very happy with the results. Two of his longtime friends, the director John Sayles and producer Maggie Renzi, told me Mark has “issues” with his father, and the film doesn’t reflect Haskell’s big-hearted kindness. Then again, they share Haskell’s left-wing beliefs. Mark, perhaps not coincidentally, does not. “He gets up every morning and he rants against what’s happening in the world,” says Haskell’s fellow documentarian Pam Yates, with admiration. In the film, he takes Mark along to a peace rally in San Francisco, where he seems to know everybody.

All fathers and sons have issues. If “Tell Them Who You Are” had been a sunny doc about how great the old man was, it wouldn’t be worth seeing — and wouldn’t be the kind of film Haskell himself makes. What Mark does, better perhaps than either he or his father realizes, is to capture some aspects of a lifelong rivalry that involves love but not much contentment. Mark remembers his father advising him, “Tell them you’re Haskell Wexler’s son,” which would have done him some good in Hollywood, but Mark has been trying for years to be defined as not simply Haskell’s son, and this film about his father is paradoxically part of that struggle. This generational thing has been going on for a while with the Wexlers; as a young man, Haskell organized a strike against his own father’s factory. And, although he came from a well-to-do family, we learn that Haskell volunteered for the Merchant Marines in World War II, and survived a torpedoed ship. This is a man who has been there.

“I don’t think there’s a movie that I’ve been on that I wasn’t sure I could direct it better,” Haskell says in the film. We learn of a few films he was fired from when the directors felt he was making that all too clear; one of them was “One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest,” and we get the memories of director Milos Forman (“he was sharing his frustrations with the actors”) and producer Michael Douglas (“He reminds me of my own father: critical and judging”).

There were also films he walked away from on matters of principle. After one, he told me the director was lazy and didn’t treat people with respect. Haskell isn’t an obedient hired hand but a strong-willed artist who gets the admiration of strong directors like John Sayles (“Limbo,” “The Secret of Roan Inish“), Norman Jewison (“In the Heat of the Night”), Mike Nichols (“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf“) and Hal Ashby (“Bound for Glory“). He won Oscars for his work on “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” and “Bound for Glory,” and was nominated three other times. On the other hand, Francis Ford Coppola replaced him on “The Conversation” (after Haskell had finished the legendary opening sequence). Haskell’s version: He was working too quickly for Coppola, who wasn’t prepared. Coppola’s version: Unstated. And Haskell believes he shot more than half of Terrence Malick’s “Days of Heaven,” which Nestor Almendros won an Oscar for. After the lights went up at the Toronto Film Festival premiere of the film, there was Norman Jewison sitting across the aisle and observing, “He could be a son of a bitch.” The way he said it, it sounded affectionate.

What Haskell is sure of is that he knows more about making documentaries than Mark does. He tells Mark he should have employed a sound man for some scenes shot at a party, and he turns out to be right. The two men get into a heated argument when Mark tries to set up a shot with his father standing in front of a sunset, and Haskell thinks his son is valuing form over content; forget the sunset, he says, because “I desperately want to say something.” On the other hand, he criticizes Mark for having him “say everything” instead of using the technique of telling through showing.

Mark provides a good overview of his father’s career: The Academy Awards, the great films, the legendary reputation. He talks to some who love him and some who don’t. We learn of Haskell’s business partnership and close friendship with Conrad L. Hall, another great cinematographer; Mark sometimes felt closer to Conrad than to his own father, and strangely enough, Conrad’s son, also a great cinematographer, felt closer to Haskell.

Then there is the issue of Mark’s mother Marian, Wexler’s wife for 30 years, now a victim of Alzheimer’s disease. I’ve know Haskell only with his third wife Rita, and I see a couple glowing with love. Mark resents his father for leaving his mother. But then we see probably the film’s strongest scene, and it involves Haskell visiting Marian in a nursing home. Marian doesn’t recognize him, but Haskell speaks softly to her: “We’ve got secrets, you, me. We’ve got secrets. We know things about each other that nobody else in the world knows.” There are tears in his eyes.

Certainly only a family member could have had access to such a scene. Possibly Haskell did not expect it to be in the documentary. But it reflects well on him, and on Mark for including it. There is this: Haskell agreed to be in the film, to some degree in order to help his son. And although Mark shows the tension between himself and his father, he also shows a willingness to look beyond the surface of his resentments.

Jane Fonda says of them: “Intimacy was not their gift.” They are still working at it. This is a film about a relationship in progress.