“The Ballad of Jack & Rose” is the last sad song of 1960s flower power. On an island off the East Coast a craggy middle-age hippie and his teenage daughter live alone in the remains of a commune. A generator is powered by wind. There is no television. Seaweed fertilizes the garden. They read. He home-schools her. They divide up the tasks. When Rose looks at Jack, her eyes glow with worship, and there is something wrong about that. When they lie side by side on the turf roof of their cottage, finding cloud patterns in the sky, they could be lovers. She is at an age when her hormones vibrate around men, and there is only one in her life.

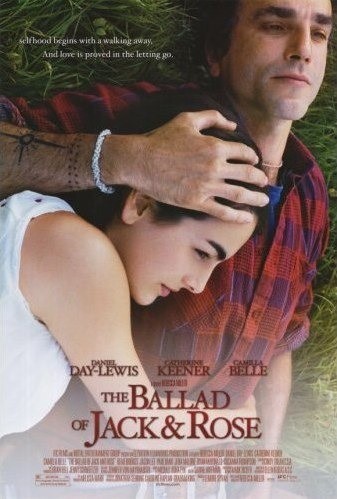

Rebecca Miller‘s film is not about incest, but it is about incestuous feelings, and about the father’s efforts, almost too late, to veer away from danger. Jack (Daniel Day-Lewis) is a fierce idealist who occasionally visits the other side of the island to fire shotgun blasts over the heads of workers building a housing development. Rose (Camilla Belle) admires him as her hero. “If you die, then I’m going to die,” she tells him. “If you die,” he says, “there will have been no point to my living.”

This is not an academic discussion. He’s had a heart attack, and he may die. She regularly takes away his home-rolled cigarettes, but out of her sight he’s a chain-smoker, painfully thin, his idealistic serenity sometimes revealing a fierce anger just below the surface. He hates the developer (Beau Bridges) who is building the new homes on what Jack believes are wetlands: “That’s not a house. It’s a thing to keep the TV dry,” he says, and “They all want to live in places with people exactly like themselves, and have private police forces to keep their greedy little children safe.”

Jack is being forced to think about the future. His daughter, he finally realizes, is too fixated on him. He visits the mainland, where for six months he has been dating Kathleen (Catherine Keener). He asks her to move with her two teenage boys out to the island and live with them: “It will be an experiment.” Because he has a trust fund, he can write her a handsome check to make the move more practical. Kathleen, who lives at home with her mother, needs the money and is realistic about that while at the same time genuinely liking Jack. But how much does she know about him? She has never been to the island.

The film’s best scenes involve the introduction of these three outsiders into the solitude of Jack and Rose. The sons, by different fathers, are different creatures. Rodney (Ryan McDonald) is an exomorphic sweetheart; Thaddius (Paul Dano) is a skinny pothead. “I’m studying to be a women’s hairdresser,” Rodney tells Rose. “I wanted to be a barber, but men don’t get enough pleasure out of their hair.”

Having possibly fantasized herself as her father’s lover, Rose reacts with anger to the newcomers and determines in revenge to lose her virginity as soon as possible. She asks Rodney to sleep with her, but he demurs (“I am sure my brother will be happy to oblige”) and suggests a haircut instead. The short-haired Rose seems to have grown up overnight, and in reaction to her father’s “experiment” offers him evidence of an experiment of her own.

The fundamental flaws in their idyllic island hideaway become obvious. As long as Jack and Rose lived in isolation, a certain continuity could be maintained. But the introduction of Kathleen as her father’s lover, and the news that she is to start attending a school in town, cause Rose to rage against the loss of — what? Her innocence, or her ideas about her father’s innocence?

Rebecca Miller, the writer and director, had a strong father of her own, the playwright Arthur Miller. She had a strong mother, too; the photographer Inge Morath. That she is now essentially the photographer (although the cinematography is by the visual poet Ellen Kuras) and her subject is a father and daughter may show her not acting out her own childhood, as some writers have suggested, but identifying with her mother. It would be reckless and probably wrong to find literal parallels between Rebecca and Rose, but perhaps the film’s emotional conflicts have an autobiographical engine.

Toward the end of the film, events pile up a little too quickly; there are poisonous snakes and sudden injuries, confrontations with the builder and medical concerns, and Jack resembles a lot of dying characters in the movies: His health closely mirrors the requirements of the story. By the end I had too much of a sense of story strands that had strayed too far to be neatly concluded, and there is an epilogue that could have been done without.

Despite these complaints, “The Ballad of Jack & Rose” is an absorbing experience. Consider the care with which Miller handles a confrontation between Jack and the home-builder. Countless cliches are sidestepped when Jack finally sees their conflict for what it is, not right against wrong, but “a matter of taste.” Is it idealistic to want a whole island to yourself, and venal to believe that other people might enjoy having homes there? The movie has a sly scene where Jack and Rose visit one of the model homes, which to Jack is an abomination and to Rose a dream.