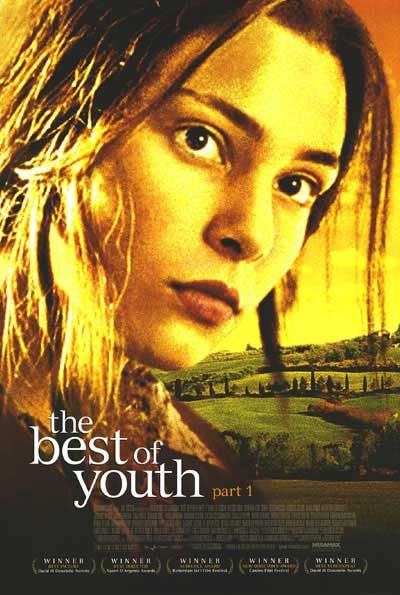

Every review of “The Best of Youth” begins with the information that it is six hours long. No good movie is too long, just as no bad movie is short enough. I dropped outside of time and was carried along by the narrative flow; when the film was over, I had no particular desire to leave the theater, and would happily have stayed another three hours. The two-hour limit on most films makes them essentially short stories. “The Best of Youth” is a novel.

The film is ambitious. It wants no less than to follow two brothers and the people in their lives from 1963 to 2000, following them from Rome to Norway to Turin to Florence to Palermo and back to Rome again. The lives intersect with the politics and history of Italy during the period: the hippies, the ruinous flood in Florence, the Red Brigades, kidnappings, hard times and layoffs at Fiat, and finally a certain peace for some of the characters and for their nation.

The brothers are Nicola and Matteo Carati (Luigi Lo Cascio and Alessio Boni). We meet their parents, Angelo (Andrea Tidona) and Adriana (Adriana Asti), their older sister Giovanna (Lidia Vitale), and their kid sister Francesca. And we meet their friends, their lovers, and others who drift through, including a mental patient whose life seems to follow in parallel.

As the film opens, Nicola has qualified as a doctor and Matteo is still taking literature classes. Matteo, looking for a job, has been hired as a “logotherapist” — literally, a person who takes mental patients for walks. One of the women he walks with is Giorgia (Jasmine Trinca), who is beautiful, deeply wounded by electroshock therapy, and afraid of the world. On the spur of the moment, Matteo decides to spring her from the institution and take her along when he and Nicola take a summer trip to the “end of the world,” the tip of Norway.

Giorgia is found by the police, but has the presence of mind to protect the brothers. Nicola continues on his journey and gets a job as a lumberjack, and Matteo returns to Rome and, impulsively, joins the army. They are to meet again in Florence, where catastrophic floods have drowned the city. Nicola is a volunteer, Matteo is a soldier assigned to the emergency effort, and in the middle of the mud and ruins, Nicola hears a young woman playing a piano that has been left in the middle of the street.

This is Giulia (Sonia Bergamasco). Their eyes meet and lock, and so do their destinies. They live together without marrying, and have a daughter, Sara. Giulia is drawn into a secret Red Brigade cell. She draws apart from her family. One night she packs to leave the house. He tries to block her way, then lets her go. She disappears into the terrorist underground.

Matteo meanwhile joins the police, takes an assignment in Sicily because no one else wants to go there, and meets a photographer in a cafe. This is Mirella (Maya Sansa). She wants to be a librarian, and he advises her to work at a beautiful library in Rome. Years later, he walks into the library and sees her for the second time in his life. They become lovers, but there is a great unexplained rage within Matteo, maybe also self-hatred, and he will not allow anyone very close.

Enough about the plot. These people, all of them, will meet again — even Giorgia, who is found by Nicola in the most extraordinary circumstances, and who will cause a meeting that no one in the movie could have anticipated, because neither person involved knows the other exists. Because of the length of the film, the director Marco Tullio Giordana has time and space to work with, and we get a tangible sense of the characters growing older, learning about themselves, dealing with hardship. The journey of Giulia, the radical, is the most difficult and in some ways the most touching. The way Nicola finally finds happiness is particularly satisfying because it takes him so long to realize that it is right there before him for the taking.

The film must have deep resonances for Italians, where it was made for national television; because of its politics, sexuality and grown-up characters, it would be impossible on American networks. It is not easy on Italy. As he is graduating from medical school, Nicola is advised by his professor: “Do you have any ambition? Then leave Italy. Go to London, Paris, America, if you can. Italy is a beautiful country. But it is a place to die, run by dinosaurs.” Nicola asks the professor why he stays. “I’m one of the dinosaurs.”

Nicola stays. Another who stays is his brother-in-law, who is marked for kidnapping and assassination but won’t leave, “because then they will have won.” With the politics and the personal drama there is also the sense of a nation that beneath the turbulent surface is deeply supportive for its citizens. Some of that is sensed through the lives of the parents of the Carati family; the father busies himself with optimistic schemes, the mother meets a grandchild who brings joy into her old age.

The film is being shown in two parts, three hours each, with separate admissions. You don’t have to see both parts on the same day, but you may want to. It is a luxury to be enveloped in a good film, and to know there’s a lot more of it — that it is not moving inexorably toward an ending you can anticipate, but moving indefinitely into a future that is free to be shaped in surprising ways. When you hear that it is six hours long, reflect that it is therefore also six hours deep.