This is not a political documentary. It is a crime story. No matter what your politics, “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room” will make you mad. It tells the story of how Enron rose to become the seventh largest corporation in America with what was essentially a Ponzi scheme, and in its last days looted the retirement funds of its employees to buy a little more time.

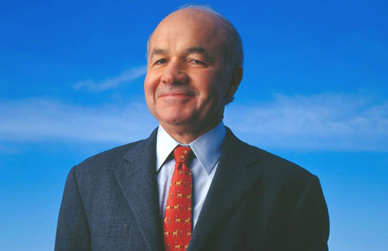

There is a general impression that Enron was a good corporation that went bad. The movie argues that it was a con game almost from the start. It was “the best energy company in the world,” according to its top executives Kenneth Lay and Jeffrey Skilling. At the time they made that claim, they must have known that the company was bankrupt, had been worthless for years, had inflated its profits and concealed its losses through bookkeeping practices so corrupt that the venerable Arthur Anderson accounting firm was destroyed in the aftermath.

The film shows how it happened. To keep its stock price climbing, Enron created good quarterly returns out of thin air. One accounting tactic was called “mark to market,” which meant if Enron began a venture that might make $50 million 10 years from now, it could claim the $50 million as current income. In an astonishing in-house video made for employees, Skilling stars in a skit that satirizes “HFV” accounting, which he explains stands for “Hypothetical Future Value.” Little did employees suspect that was more or less what the company was counting on.

Skilling and Lay were less than circumspect at times. When a New York market analyst questions Enron’s profit and loss statements during a conference call, Skilling can’t answer and calls him an “a-hole;” that causes bad buzz on the street. During a Q&A session with employees, Lay actually reads this question from the floor: “Are you on crack? If you are that might explain a lot of things. If you aren’t, maybe you should be.”

One Enron tactic was to create phony offshore corporate shells and move their losses to those companies, which were off the books. We’re shown a schematic diagram tracing the movement of debt to such Enron entities. Two of the companies are named “M. Smart” and “M. Yass.” These “companies” were named with a reckless hubris: One stood for “Maxwell Smart” and the other one … well, take out the period and put a space between “y” and “a.”

What did Enron buy and sell, actually? Electricity? Natural gas? It was hard to say. The corporation basically created a market in energy, gambled in it and manipulated it. It moved on into other futures markets, even seriously considering “trading weather.” At one point, we learn, its gambling traders lost the entire company in bad trades, and covered their losses by hiding the news and producing phony profit reports that drove the share price even higher. In hindsight, Enron was a corporation devoted to maintaining a high share price at any cost. That was its real product.

The documentary is based on the best-selling book of the same title, co-written by Fortune magazine’s Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind. It is assembled out of a wealth of documentary and video footage, narrated by Peter Coyote, from testimony at congressional hearings, and from interviews with such figures as disillusioned Enron exec Mike Muckleroy and whistle-blower Sherron Watkins. It is best when it sticks to fact, shakier when it goes for visual effects and heavy irony.

It was McLean who started the house of cards tumbling down with an innocent question about Enron’s quarterly statements, which did not ever seem to add up. The movie uses in-house video made by Enron itself to show Lay and Skilling optimistically addressing employees and shareholders at a time when Skilling in particular was coming apart at the seams. Toward the end, he sells $200 million in his own Enron stock while encouraging Enron employees to invest their 401K retirement plans in the company. Then he suddenly resigns, but not quickly enough to escape Enron’s collapse not long after. Televised taking the perp walk in handcuffs, both he and Lay face criminal trials in Texas.

The most shocking material in the film involves the fact that Enron cynically and knowingly created the phony California energy crisis. There was never a shortage of power in California. Using tape recordings of Enron traders on the phone with California power plants, the film chillingly overhears them asking plant managers to “get a little creative” in shutting down plants for “repairs.” Between 30 percent and 50 percent of California’s energy industry was shut down by Enron a great deal of the time, and up to 76 percent at one point, as the company drove the price of electricity higher by nine times.

We hear Enron traders laughing about “Grandma Millie,” a hypothetical victim of the rolling blackouts, and boasting about the millions they made for Enron. As the company goes belly up, 20,000 employees are fired. Their pensions are gone, their stock worthless. The usual widows and orphans are victimized. A power company lineman in Portland, who worked for the same utility all his life, observes that his retirement fund was worth $248,000 before Enron bought the utility and looted it, investing its retirement funds in Enron stock. Now, he says, his retirement fund is worth about $1,200.

Strange, that there has not been more anger over the Enron scandals. The cost was incalculable, not only in lives lost during the power crisis, but in treasure: The state of California is suing for $6 billion in refunds for energy overcharges collected during the phony crisis. If the crisis had been created by Al Qaeda, if terrorists had shut down half of California’s power plants, consider how we would regard these same events. Yet the crisis, made possible because of deregulation engineered by Enron’s lobbyists, is still being blamed on “too much regulation.” If there was ever a corporation that needed more regulation, that corporation was Enron.

Early in the film, there’s a striking image. We see a vast empty room, with rows of what look like abandoned lunchroom tables. Then we see the room when it was Enron’s main trading floor, with countless computer monitors on the tables and hundreds of traders on the phones. Two vast staircases sweep up from either side of the trading floor to the aeries of Lay and Skilling, whose palatial offices overlook the traders. They look like the Stairway to Heaven in that old David Niven movie, but at the end they only led down, down, down.