After Josey Aimes takes her kids and walks out on the boyfriend who beats her, she doesn’t find a lot of sympathy back at home. “He caught you with another man? That’s why he laid hands on you?” asks her father. “You can actually ask me that question?” she says. He can. In that place, at that time, whatever happened was the woman’s fault. Josey has returned to her home town outside Minnesota, where her father works in the strip mines of the Mesabi Iron Range.

She gets a job as a hairdresser. It doesn’t pay much. She can make six times more as a miner. She applies for a job and gets one, even though her new boss is not happy: “It involves lifting, driving, and all sorts of other things a woman shouldn’t be doing, if you ask me. But the Supreme Court doesn’t agree.” Out of every 30 miners, 29 are men. Josie, who is good-looking and has an attitude, becomes a target for lust and hate, which here amount to the same thing.

“North Country,” which tells her story, is inspired by the life of a real person, Lois Jenson, who filed the first class action lawsuit for sexual harassment in American history. That the suit was settled as recently as 1991 came as a surprise to me; I would have guessed the 1970s, but no, that’s when the original court decision came down. Like the court’s decisions on civil rights, it didn’t change everything overnight.

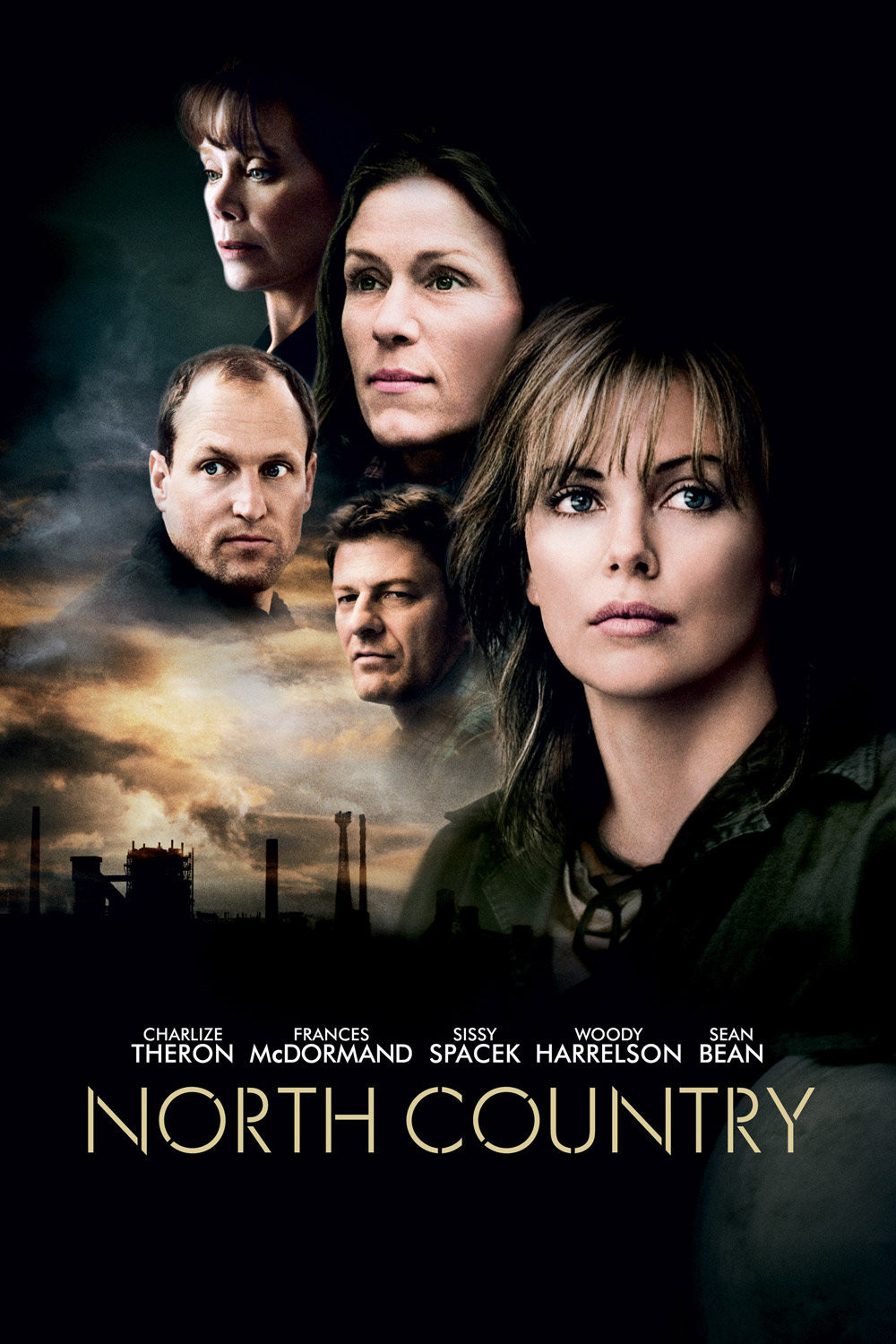

The filmmakers say Josey Aimes is a character inspired by Jenson’s lawsuit but otherwise fictional; the real Jenson is not an Erin Brockovich-style firebrand, and keeps a low profile. What Charlize Theron does with the character is bring compelling human detail. We believe she looks this way, sounds this way, thinks this way. After “Monster,” here is another extraordinary role from an actress who has the beauty of a fashion model but has found resources within herself for these powerful roles about unglamorous women in the world of men.

The difference is that her Aileen Wronos, in “Monster,” was a murderer, no matter what society first did to her. All Josey Aimes wants is a house of her own, good meals and clothes for her kids, and enough money to buy her son hockey skates once in a while. Reasonable enough, it would seem, but even her father Hank (Richard Jenkins) is opposed to women working in the mines, because it’s not “women’s work,” and because she is taking the job away from a man “who needs it to support his family.” Josey replies: “So do I.” But even the women in the community believe there’s something wrong if she can’t find a man to take care of her.

“North Country” is the first movie by Niki Caro since the wonderful “Whale Rider.” That was the film about a 12-year-old Maori girl in New Zealand, who is next in an ancestral line to be chief of her people, but is kept from the position because she is a woman. Now here is another woman who’s told what she can’t do because she is a woman. “Whale Rider” won an Oscar nomination for young Keisha Castle-Hughes, who lost to Charlize Theron. Now Theron and Caro will probably be going to the Academy Awards again.

Caro sees the story in terms of two worlds. The first is the world of the women in the community, exemplified by a miner named Glory (Frances McDormand), who is the only female on the union negotiating committee, and has a no-nonsense, folksy approach that disarms the men. She finds a way to get what she wants without confrontation. The other women miners are hard-working survivors who put up with obscenity and worse, and keep their heads down because they need their jobs more than they need to make a point. Josie has two problems: She is picked on more than the others, and one of her persecutors is a supervisor named Bobby Sharp (Jeremy Renner), who shares a secret with her that goes back to high school, and has left him filled with guilt and hostility.

In the male world, picking on women is all in a day’s work. It’s what a man does. A woman operates a piece of heavy machinery unaware that a sign painted on the cab advertises sex for sale. The women find obscenities written in excrement on the walls of their locker room. When McDormand persuades the union to ask for Porta-Potties for the women, “who can’t hold it as long as you fellas,” one of the first women to use one has it toppled over while she’s inside.

There is also all sorts of touching and fondling, but if a woman is going to insist on having breasts, how can a guy be blamed for copping a feel? After Bobby Sharp assaults Josey, his wife screams at her in public: “Stay away from Bobby Sharp!” It is assumed and widely reported that Josey is a tramp, and she is advised to “spend less time stirring up your female co-workers and less time in the beds of your male coworkers.”

She appeals to a local lawyer (Woody Harrelson), who takes the case partly because it will establish new law. It does. The courtroom protocol in the closing scenes is not exactly conventional, but this isn’t a documentary about legal procedure, it’s a drama about a woman’s struggle in a community where even the good people are afraid to support her. The court scenes work magnificently on that level.

“North Country” is one of those movies that stir you up and make you mad, because it dramatizes practices you’ve heard about but never really visualized. We remember that Frances McDormand played a woman police officer in this same area in “Fargo,” and we value that memory, because it provides a foundation for Josey Aimes. McDormand’s role in this movie is different and much sadder, but brings the same pluck and common sense to the screen. Put these two women together (as actors and characters) and they can accomplish just about anything. Watching them do it is a great movie experience.