Somewhere in the back of nowhere, in an adobe house with no lights or running water, a family lives in what could be called freedom or could be called poverty. We’re not sure if they got there because they were 1960s hippies making a lifestyle experiment or were simply deposited there by indifference to conventional life. They grow vegetables and plunder the city dump and get $320 a month in veterans’ benefits, but they are not in need and are apparently content with their lot.

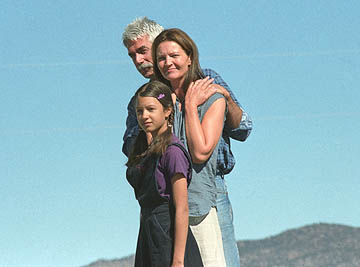

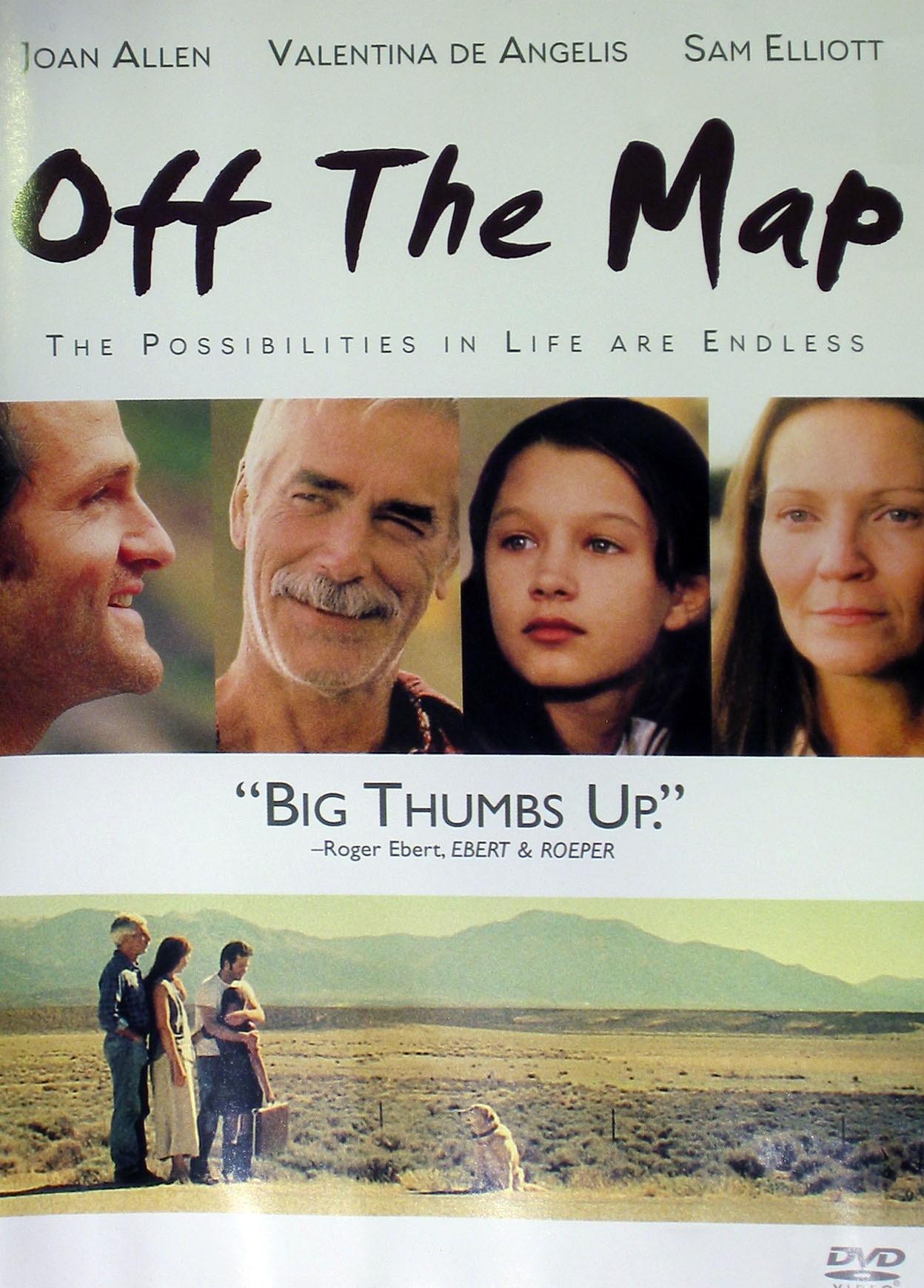

Now there is a problem. “That was the summer of my father’s depression” the narrator tells us. She is Bo Groden, played in the movie by Valentina de Angelis at about age 12, and heard on the sound track as an adult (Amy Brenneman). “I’m a damn crying machine,” says her dad, Charley (Sam Elliott). He sits at the kitchen table, staring at nothing, and his wife and daughter have learned to live their lives around him.

His wife is Arlene, played by Joan Allen in a performance of astonishing complexity. Here is a woman whose life includes acceptance of what she cannot change, sufficiency within her own skin and such simple pleasures as gardening in the nude. She is a good wife and a good mother, but not obviously; it takes us the whole movie to fully appreciate how profoundly she observes her husband and daughter, and provides what they need in ways that are below their radar.

Charley has a friend named George (J.K. Simmons), who sort of idolizes him. Sometimes they fish, sometimes they talk. Arlene wants George to impersonate Charley, visit a psychiatrist and get some antidepressants. George would rather fish. One day a stranger arrives at their home, which is far from any road. He carries a briefcase, says he is from the IRS and is there to audit them, since the Groden family has reported an annual income of less than $5,000 for several years.

This man is William Gibbs (Jim True-Frost). He is stung by a bee, takes to the sofa, confesses his dissatisfaction with tax collecting and, what with one thing and another, never leaves. Eventually, he ends up living in an old school bus on the property. He falls in love with Arlene, in a non-demonstrative way, and is good company for Charley. “Ever been depressed?” Charley asks him. “I’ve never not been,” William says.

These characters in this setting could become caricatures or grotesques. But the director, Campbell Scott, and the writer, Joan Ackermann, refuse to underline them or draw arrows pointing to their absurdities. They accept them. Their movie is freed from a story that must hurry things along; life unfolds from day to day. Will Charley recover from his depression? Will William leave? Will Bo, who is being home-schooled, get to go to a real school? The movie suggests no urgency to get these questions answered.

Instead, in a stealthy and touching way, it shows how people can work on one another. Charley may be depressed because of a chemical imbalance, or he may be stuck because his life offers him no opening for heroism. Arlene keeps herself entertained by surprising herself with her oddities; she handles financial emergencies by observing with detachment that sooner or later they will probably have to deal with them. Bo keeps busy writing letters to food corporations, complaining about insect parts found in their products, and composing personal questions for the Ask Beth newspaper column. William Gibbs starts to paint and completes a watercolor, 3 feet high by 41 feet long, showing the earth meeting the sky.

It is not clear if William has joined them to heal, to escape or to die. But his presence in the family, which is accepted without comment, budges the emotional ground under Charley just enough so that he slides toward the edge of his depression. Perhaps it is William’s undemonstrative love for Arlene, never acted on, that reawakens Charley’s desire for this magnificent beast, his wife.

Campbell Scott is an actor, and as a director he is able to trust his actors entirely. If they are doing their jobs, we will watch, no matter if the story centers on a man sitting at a table and everyone else essentially waiting for him to get up. The life force bubbling inside young Bo, suggested by de Angelis in a performance of unstudied grace, lets us know things will change, if only because she continues to push at life. “Off the Map” is visually beautiful as a portrait of lives in the middle of emptiness, but it’s not about the New Mexico scenery. It’s about feelings that shift among people who are good enough, curious enough or just maybe tired enough to let that happen.

Variety, the show-biz bible, always assesses a movie’s commercial prospects in its reviews. Its chief critic, the dependable Todd McCarthy, loves this film, but does his duty to the biz by noting: “Pic’s unmelodramatic nature and unmomentous subject matter will make this a tough sell even on the review-driven specialized circuit.”

True, which explains why the film premiered at Sundance 2003 and is opening only now. But it is opening, and by now you have sensed whether you would like it or not. If you think you would not, be patient, for sooner or later you will find yourself compelled to get up from the table.