Alan Parker Movie Reviews

Blog Posts That Mention Alan Parker

Looking Back at Alan Parker’s Mississippi Burning

Seongyong Cho

Alan Parker: 1944-2020

Peter Sobczynski

One shot: They wrote that

Jim Emerson

Oscars: No comment (almost)

Jim Emerson

Up With Contempt!

Jim Emerson

You Play Well: Diane Keaton (1946-2025)

Scout Tafoya

Part of the Solution: Matthew Modine on Acting, Empathy, and Hard Miles

Matt Zoller Seitz

When Paul Simon Bombed at the Movies

Tim Grierson

Cannes 2021: Where is Anne Frank, Stillwater, Lamb

Jason Gorber

The Whole Parade: On the Incomparable Career of Nicolas Cage

Scout Tafoya

Revisiting John Williams’ Score for Jaws, 45 Years Later

Charlie Brigden

Dylan, Dublin and a Bit of Magic: Lance Daly Reflects on Kisses, Ten Years After Its U.S. Release

Matt Fagerholm

Playing it Luce: Questions for a complicated movie

Omer M. Mozaffar

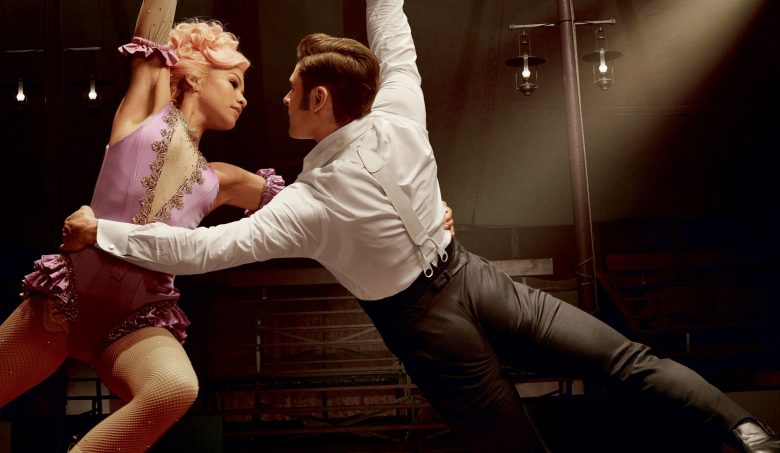

30 Minutes on: “The Greatest Showman”

Matt Zoller Seitz

The “Shawshank” Greatness, Part II

Gerardo Valero

The Best of the d’Ors

Michał Oleszczyk

Stone Reader

Roger Ebert

The Best 10 Movies of 1996

Roger Ebert

The Best 10 Movies of 1988

Roger Ebert

The Best 10 Movies of 1987

Roger Ebert

Who killed the movies?

Jim Emerson

“You’re taking this very personal…”

Jim Emerson

The Ultimate Movie Quiz (and Free Personality Inventory!)

Jim Emerson

Stanley Kubrick hates you

Jim Emerson

I am pleased to do Kevin Smith a small favor

Jim Emerson

Simply the worst

Jim Emerson

The Return of the Autobiographical Dictionary of Film

Jim Emerson

The Evil, the Bad and the (Self-)Important

Jim Emerson

Darkness for ‘Donnie Darko’ director?

Jim Emerson

Video games: The ‘epic debate’

Jim Emerson

A Lincoln who creaks with every step

Omer M. Mozaffar

Ebertfest: Synecdoche, Champaign-Urbana

Roger Ebert

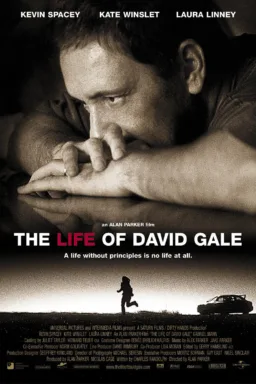

Spacey gets object lesson in the fine art of the deal

Roger Ebert

Cannes all winners

Roger Ebert

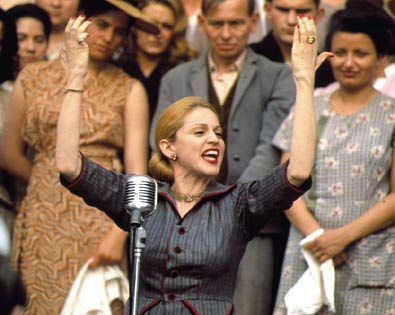

Madonna: possessed by “Evita”

Roger Ebert

Movie Answer Man (02/23/1997)

Roger Ebert

Movie Answer Man (12/29/1996)

Roger Ebert

Movie Answer Man (11/12/1995)

Roger Ebert

Movie Answer Man (05/07/1995)

Roger Ebert

Popular Reviews

The best movie reviews, in your inbox