The term “listicle” has been kicked around a lot in Cannes this year, so even though I revile the sound of it, I decided to make one of my own. The main award of the festival, Palme d’Or, is seen as the art house equivalent of the Oscar: there is no better proof that you are a true auteur of cinema than getting one of those unassuming and elegant golden twigs. In the past, various juries made both great and horrible choices, and today I want to remind you of some of the Cannes winners that stayed with me forever. My selection process started with 1955, since that is when the first Palme d’Or was awarded (even though the Cannes festival gave out awards before, too, simply called “Grand Prix”).

Without further ado, here are my favorite Palme d’Or winners:

1. “Secrets and Lies” (1996, Mike Leigh)

Mike Leigh has been perfecting his skills as an unconventional portrayer of working-class British families for years, and this movie is his masterpiece. Leigh’s unique, semi-improvisational way of developing scripts with actors yielded great authenticity to what is basically a heartbreaking story of loneliness within one’s own family. The 6-minute two-shot of Brenda Blethyn realizing that Marianne Jean-Baptiste is in fact her daughter more than makes up for the price of admission.

2. “Taxi Driver” (1976, Martin Scorsese)

Still the single best (post-)Vietnam movie and the most harrowing vision of big city alienation ever put on film. Fun Cannes fact: the movie competed here against, among others, Alan Parker’s “Bugsy Malone.” That kiddie musical also ends with a massacre, albeit the most benign one you will ever see (hint: whipped cream for bullets).

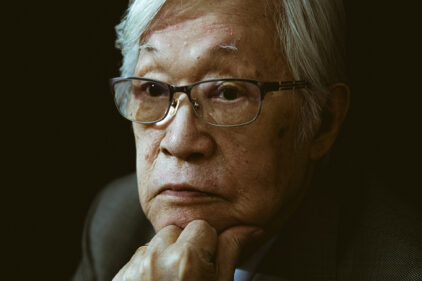

3. “Ballad of Narayama” (1983, Shoei Imamura)

One of the bleakest and most harrowing films ever made depicts a Japanese village in which the elderly are sent up the titular mountain to die and thus relieve the small community of the burden that taking care of them entails. The movie is brutal and beautiful at the same time, and Imamura is both unblinking and strangely serene in the face of death. Fun Cannes fact: “Ballad…” competed here against “Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life,” which was no less bleak in its outlook—if much (much) funnier in content.

4. “All that Jazz” (1979, Bob Fosse)

Speaking of dying, did you see that great musical number based on cardiac arrest…? Roy Scheider stars as Fosse’s alter ego in this unique feat of movie bravado: an innovatively cut, stunningly assured musical about saying goodbye to life on the stage—as well as to the stage of life. It tied at Cannes with “Apocalypse Now”. Those were the days.

5. “Rosetta” (1999, Jean-Pierre Dardenne, Luc Dardenne)

The Dardennes are among the select group of double Palme d’Or winners (also including Emir Kusturica, Bille August, Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Haneke and Shoei Imamura), but their first Palme is still their best. The struggle of a barely articulate, unlovely and fiercely resilient young woman to own her own food stand and make a living for herself and her mother has a force of “The Bicycle Thieves” and a you-are-there style that influenced an entire generation of modern filmmakers. Will the Dardennes be winning for the third time with this year’s “Two Days, One Night”? We’ll be seeing shortly.

6. “Pulp Fiction” (1994, Quentin Tarantino)

Is any introduction necessary? QT’s first masterpiece is an artfully rolled burrito of a movie, filled with stuff both great and questionable, sweet and spicy, and just about impossible to put away. It’s been 20 years since it scooped the Palme and some folks still feel like it was Krzysztof Kieslowski’s haute-couture drama “Three Colors: Red” that deserved the prize, but despite my Polish patriotism, I do not agree. This movie manages to be so many things at once (a comedy, a fable, a morality play, a supreme mixtape, a source of inspiration and imitation alike), it’s fully earned its place in the everlasting canon.

7. “The Conversation” (1974, Francis Ford Coppola)

Quite simply the greatest movie on loneliness ever made, this post-Watergate study in the destructive power of surveillance was Coppola’s first Palme (he won the second for an unfinished cut of “Apocalypse Now”). Gene Hackman pulls you right inside the hollow, battered heart of his guilt-driven, sexually- and emotionally-stifled Harry Caul, while the unforgettable sound editing by Walter Murch (as well as the haunting score by Dave Grusin) really makes you *listen* to the screen in a way that changes your relationship to the medium.

8. “Man of Iron” (1981, Andrzej Wajda)

The only Palme d’Or to be awarded to a Polish film went to this white-hot political drama, shot by Andrzej Wajda in the midst of Solidarity shipyard strikes and still serves as a documentary of that crucial time in Cold War history. A sequel to the groundbreaking “Man of Marble,” it picks up where the previous movie left off, with the specters of the past largely gone and with communist Poland in time-changing convulsions. You can still feel the immediacy of the film, not least in watching Lech Walesa’s cameo as himself. Fun Cannes fact: Wajda competed against Andrzej Zulawski’s “Possesion,” a movie that couldn’t be more different in tone and style (suffice to say it includes Isabelle’s Adjani famous sex scene with a gigantic octopus, of which I wrore more here.

9. “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” (1964, Jacques Demy)

Every line of (largely unrhymed) dialogue is sang, every frame is a gaudy puff of eye candy floss, and Catherine Deneuve is loveliness itself, no matter how you light her. The movie is one-of-a-kind: a cheap melodrama transformed by its unique form and heartfelt approach; you are bound to cry your heart out at the end. Popular movies haven’t really approached this kind of Chaplineque purity of simple emotion since (although “The Artist” certainly tried).

10. “Under the Sun of Satan” (1987, Maurice Pialat)

A largely reviled jury choice at the time (Pialat shook his fist at the booing Cannes audience, shouting: “I don’t like you, either!”), this adaptation of a Georges Bernanos novel is a classic of Catholic anguish that’s somehow entirely secular in its approach and tone. Gerard Depardieu plays a priest much surer of existence of Satan than he is of God, and Pialat’s sparse, merciless style makes you feel the man’s overwhelming spiritual hunger. A difficult, but richly rewarding film that remains largely unknown to most viewers.