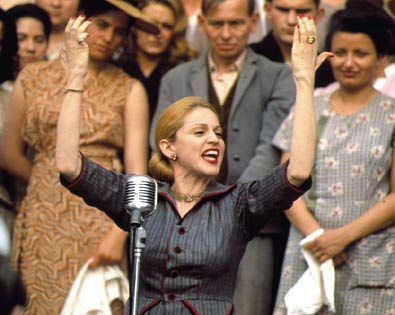

LOS ANGELES–Madonna, who has always insisted she was the best choice to play Eva Peron, may have been right. It is not only that she holds the screen with charisma and force in the film version of “Evita,” but that she understands from the inside out how Evita invented herself – how she used fashion and stage presence and personal flair to make herself seem bigger than life.

Consider the problem of the president of Argentina. Alan Parker, the director, requested permission to shoot on Eva Peron’s famous balcony in the Plaza De Mayo in Buenos Aires. Permission was denied. Every member of the Cabinet was approached. No soap. Finally Madonna went personally to make a call on the president. After their conversation, permission was granted to use the sacred balcony.

“What did you use on him?” I asked her. “Psychic power?”

“I think it was excellent-smelling perfume,” she said. “I think at that point I was possessed by her. I went in costume to the meeting, and I think that he picked up on my passion for her, or suddenly saw a different point of view.”

It is not too big a stretch to envision the original Evita making a call to the presidential office, also with passion, also with perfume, and getting what she wanted. The other actresses considered for the role (and they are both wonderful: Meryl Streep and Michelle Pfeiffer) would have brought other qualities, but can you imagine either one of them deciding which perfume would best seduce the president?

Evita was the rock star as politician’s wife. She adored the movies. She would not have been oblivious to the cult of personality that fed on such personages as Churchill, Hitler or DeGaulle. Born poor and illegitimate, she understood how the movies fed the souls of the disenfranchised with images of power and glamor. She used that knowledge to create herself in the image of a star, and then she found the politician to whom she could attach herself (or was it Evita who swept Juan Peron behind her?).

“Most of her politics were instinctive,” Madonna told me. This was the day before the movie’s Hollywood press premiere, in early December (the film opens nationally on Wednesday). “Peron was the person who understood the dogma of politics. He was the intellectual of the two, and she had the natural instincts. She was the person that could relate to the people and that’s why they worked so good together and that’s why they were so great for each other. She totally operated on street smarts and instincts, absolutely.”

And so, some would say, has Madonna, who also willed herself to worldwide celebrity, who reinvents her image with each tour and has done it yet again, trading in the strutting sleaze queen for her new incarnation as serious musical star and new mother.

She seemed quieter, more thoughtful, when I talked to her; there was none of the cheerful desire to shock that I remembered from the 1991 Cannes Film Festival, when she paused on the steps of the Palais and threw open her cloak to reveal what appeared to be stainless steel underwear. Remembering her standing there, bathed in floodlights, covered on every TV channel in Europe, cheered by thousands of fans, I asked her what Evita was thinking about as she stood on the Plaza De Mayo balcony. In the movie, it is the moment of her great early triumph, when she realizes she has reached the summit.

“I think that she must have felt incredibly loved,” Madonna said. “I think she must have felt a real sense of victory, of accomplishment. When you spend your entire life having people say you’ll never amount to anything or you’re no good or you don’t have what it takes, to finally have achieved what she achieved must have been the ultimate revenge.”

And, I continued, what were you thinking when you stood on the red carpet in front of the Palais de Festival in Cannes, and the band was playing and the paparazzi were going crazy – what does that feel like for someone? Is it like Evita’s feelings?

“It’s a rush, that’s for sure,” she said. “Especially the first time it happens. It’s incredibly overwhelming; it’s confusing. And you do feel an enormous sense of love. Yeah.”

I think a rock star was a good choice for this role, because you know what it feels like to be the spotlight of this kind of mob adoration, I said. Mainstream actresses work mostly just in front of a camera, and never have that experience.

“Well, she definitely fed off the energy of the people, and she whipped them up into frenzy, that’s for sure,” Madonna replied. “And she gave them what they wanted. They wanted her to dress up; they wanted her to come out with the fantastic hats and the beautiful jewels and the incredible hairdo. They wanted someone to look up to, especially because she came from poverty. She was from the working class, and they could say to themselves, well, look, she did it, and if she did it, I can do it.”

How do people envision that? How do they invent that for themselves?

“You mean, your everyday Joe on the street?”

Let’s put it this way, most of us never put ourselves on a path to get ourselves in front of 10,000 screaming people. Some of us do. You have to be able to imagine yourself in that position.

“I can assure you I never imagined myself in front of 10,000 people. Since I was a child (I cannot lie) I’ve always enjoyed having an audience – but 10,000 people is something you cannot imagine. It evolves into that. I can honestly say I never expected what’s happened to me, and I could never have expected, like, performing, for instance, in a soccer stadium in front of 120,000 people.”

After I said it, I realized 10,000 was a pretty conservative number. When she arrived in Argentina to play Eva Peron, however, Madonna was not welcomed like Evita’s second coming. There were demonstrations, there was rude graffiti on the road from the airport, and she was greeted with protests, headlines, resentment, even hatred.

People wanted Madonna to. . .

“. . . get out! I think they were angry that, you know, that we were coming in and making a movie about their heroine when they hadn’t done it themselves. I think that kind of ticked them off. And then there were the people who thought she was a saint. They thought only Mother Teresa could portray her in a movie. Then there were other people who thought she was a sinner, and they didn’t want a tribute being made to her. So it got very confusing.

“If you go out into the provinces, they still have her picture on their walls. She had a profound effect on these people. I can’t explain it. Plus, she died so young, and she’s been kept alive in that sort of myth-making machine.”

The protests helped to firm the government’s opposition to allowing Madonna to film (or even stand) on Evita’s balcony. But then the president came around.

“I think up until that point, all he had to go on was hearsay,” she said. “The stage version of the musical portrays a very one-dimensional version of her. It doesn’t show her in a very humane way; it doesn’t show any vulnerability, it doesn’t explain her past. Alan Parker had the chance to do that in a movie, and I explained that to the president. I also think that once he heard the music, he was very moved by it. I played him a lot of the stuff that we had already recorded, and I think that I convinced him that we were going to treat her in a respectful manner in the film.”

The music was already recorded, because, of course, there was no way to record live soundtracks in scenes on location with thousands of extras and marching troops and roaring engines and cheering throngs. In a film with almost no spoken dialogue – it’s sung all the way through, like an opera – the music had to be perfect. The director couldn’t march his thousands of extras back and forth for days while the actors worked on a note. So the score was recorded in England, and then in Argentina the actors had to match every nuance of it.

“What we had to do was a very long process,” Madonna said. “First, we had to rehearse the scenes with all the actors right in a room and get the physicality of everything and the right sort of emotional intensity. Then we went into the recording studio and did the same thing. Then we got separated into different isolation booths and we could see each other through the Plexiglas and we were still acting the scenes out. It was very bizarre.

“Then there were a lot of scenes that we weren’t sure about, so we had options. We would have subtler takes on things and more dynamic takes on things, so that when we were filming we would have choices. The last third of the movie, which is certainly the most emotional portion of the movie, for the most part we did live because there’s no way we could have matched everything. You can’t cry on cue. I was very happy that we got to do those scenes live. That was the best.”

In most movies, I said, everything depends on the star, the subject of the shot. But here you had a lot of shots where everything depended upon these enormous military-style logistics with the extras and the troops and all the spotlights, and when they got everything going, then you had to hit your mark, bang!, and if you didn’t do it then they had to do it all over again. That must have been difficult.

“It was. On the other hand, it was a lot like when you’re on tour and you’re doing a full-scale show that involves an incredible amount of lights and choreography and musicians and you have to hit marks then, too. It’s kind of similar.”

In the days leading up to the premiere, Madonna was also playing the role of new mother. A suite was reserved for her in the Marina Del Rey hotel where her interviews took place, and she slipped upstairs for mothering time on a regular basis. People who had been around her a lot said she seemed calmer, quieter.

“I feel that,” she said.

Is that what happens?

“I think it’s been a combination. First, making this movie, which was such a challenge and such a learning experience. It was two years of my life, and it was so fulfilling to me as an artist. It gave me the chance to work on every aspect of my life, of myself, as a creative person. Then having a child has also been incredibly fulfilling and centering. Both of those things have changed me.”

Did people tell you that it was bad for the trajectory of your stage and recording career to take off two years and work on a film project that wasn’t your main job, so to speak?

“Not one person told me I shouldn’t do this. Everyone thought it was a great idea.”

But it’s unconventional to say for two years that you’re not going to tour, you’re not going to do anything but focus on this movie.

“This is true. But I’m no stranger to unconventional.”