Schoolkids who are facing midnight on Sunday and still haven’t written their school papers on P.T. Barnum had better not turn to the musical extravaganza “The Greatest Showman” for notes. This majestically asinine film elides or ignores much of the circus founder’s life, and turns what’s left to such hash that calling the film a biography seems generous—but then, I doubt that director Michael Gracey and his collaborators would expect anybody to call it that, so maybe it’s bad faith to criticize the movie on those grounds. “Showman” is more like a set of fanciful, often nonsensical variations on the life of Phineas T. Barnum (Hugh Jackman). It treats him as a standard-issue poor boy who made good, yet still let pride get the better of him, by over-expanding his business, and by becoming so infatuated with Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind (Rebecca Ferguson of “Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation”) that he jeopardized his otherwise sublime marriage to Charity (Michelle Williams), mom of his two adorable daughters (Austyn Johnson and Cameron Seely).

The film also weaves in lots of scenes that are meant to make us think that Barnum was the first 21st century-style “woke” white straight man in America—a goodhearted fellow who gave circus jobs to outcasts of one kind or another (talk about a big tent: the repertory company includes African-Americans, little people, giants, conjoined twins and a bearded lady), not just because they happened to possess certain talents or physical characteristics that Barnum could exploit (often by appealing to the majority’s prurient interests or bigotries) but because the onetime poor boy Barnum sees himself in their striving, and wants to build a theatrical-carnival arts utopia in America’s largest city with help from his new partner, rich kid turned playwright Philip Carlyle (Zac Efron).

A lot of “Showman” is less concerned with the specifics of Barnum’s life and times than with sentimentalizing aspects of show business, in particular the way it can provide a makeshift family for people whose biological families rejected them. The film began production in New York in November, 2016, right after the presidential election, and the screenplay (by “Sex and the City” writer Jenny Bicks and “Dreamgirls” director Bill Condon) contains many images and situations that feel like direct challenges to Trump-style politics of resentment. The most affecting early scenes show Barnum putting together his troupe by auditioning people who’d been marked as outcasts, including Keala Settle as the Bearded Lady Lettie Lutz and Sam Humphrey as the dwarf Charles Stratton, re-christened General Tom Thumb and placed on horseback in a Napoleon outfit. A secondary plotline focuses on the white Carlyle’s love for acrobat Anne Wheeler (Zendaya), a light-skinned black woman, and Carlyle’s parents’ resentment of their relationship. In key sequences, the film pits a mob of howling white reactionaries who think the circus is disgusting and immoral against Barnum’s multicultural, gender-bending, and body-type-diverse band of “Others.”

All this stuff will be easier for viewers to embrace if they don’t know that the real Barnum was a very American fusion of exploitative hucksterism and noble sentiments, building part of his fortune on minstrel performance and appeals to racist fascination, but also becoming a sincere abolitionist and agitating for the 13th Amendment later in life. A more compromised or confused Barnum would’ve put audiences off, though. So this version is Charles Foster Kane, only sweet and self-made, and without the domineering dark streak. And he’s played by twinkly-eyed Hugh Jackman.

From the stylized, trailer-like opening images of Barnum semi-silhouetted in the arena (intercut with opening titles), through the hip-hop influenced choreography and corny R&B-inflected singing style and instrumentation, to the musical montages that work physical actions (such as hammering and sweeping) into the fabric of the score, “The Greatest Showman” is a compendium of every storytelling and pop music cliche of recent times. The movie’s release year might as well have been stamped in the corner of every frame like a watermark. This is not a good or a bad thing, of course; it’s just a thing—all films are products of the time in which they were made, and usually tell you more about that time than whatever era they’re set in. Consider Alan Parker’s “Bugsy Malone,” which takes place in the 1920s and ’30s, or Ken Russell’s “Lisztomania,” which is set in the 1880s. Both movies feature then-current 1970s musical styles in their soundtracks (by Paul Williams and Yes, respectively). As you watch “The Greatest Showman,” you don’t have to squint very hard to discern the influence of Lin Manuel-Miranda’s “Hamilton,” Beyonce’s “Lemonade,” and Ryan Murphy’s “Glee.” Going back further on the pop culture timeline, Bob Fosse’s influence also looms large—in particular his film version of “Cabaret,” which juxtaposed the comforting secret society of cabaret performance, with its tolerance for misfits, against the rise of ruddy-faced German race-hatred.

Ultimately, though, this is an imaginatively directed musical melodrama that splits the difference between the old, pre-1960s style of filmed musical and the more jagged, post-rock-‘n’-roll style. “Showman” is choreographed and directed within an inch of its glittery life, but never in a frenetic or imprecise way. You never get the sense that they just shot everything from 12 camera angles and cut it all together later and hoped it would work somehow. Every shot feels purposeful, even when the film is rushing through a montage to set up the next big twist. Choices were quite obviously made and stuck with, and many of these are thoughtful and tasteful, even when the story itself panders. The movie is always working with the music, never adjacent to it or in spite of it. Director Gracey, choreographer Ashley Wallen, songwriters Benj Pasek and Justin Paul (of “La-La Land”) and cinematographer Seamus McGarvey (“Atonement,” “The Avengers“) think about each number as a self-contained short film, with its own “story” and little marks that the major characters have to hit in order to progress.

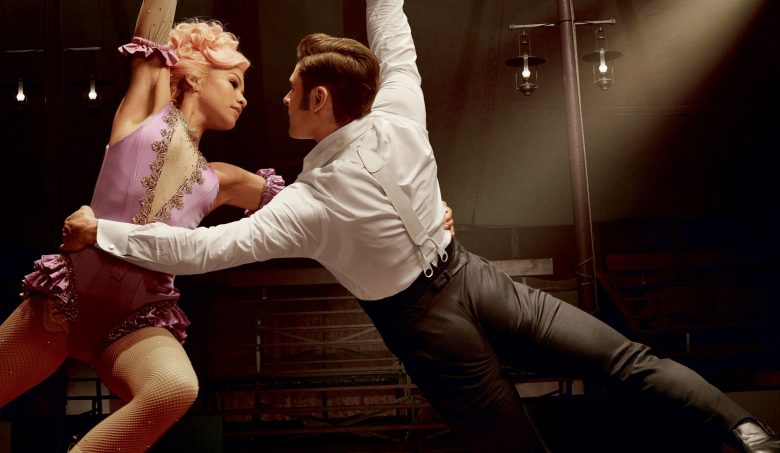

The latter are always demarcated with dance moves that involve significant objects, such as the liquor bottles and glasses and bar stools deployed in a Gene Kelly-like barroom duet between Carlyle and Barnum, and the way that a pivotal number involving Carlyle and Anne Wheeler is built around a ring suspended from a knotted rope (the year’s best action scene, probably). Another, less flashy but equally impressive number finds Charity missing Barnum while he’s off touring Europe with his new star (and respectability insurance policy) Jenny Lind. This entire scene is built around the idea of absence, and the filmmakers get it across simply, by including a prominent empty chair in shots of dinner tables or school recitals, or by working a Barnum-shaped shadow into some part of the frame.

Even when the movie’s dumber contrivances make you roll your eyes, the performers’ sincerity wins the day. Zendaya, Williams, Settle, Humphrey, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (as Anne Hooper’s loyal, righteous brother) and Paul Sparks (as a journalist who despises Barnum for his crude populism) work wonders in roles that are largely devoid of self-awareness. Efron does some heavy-duty pining here, of a kind not seen since the era of silent movies, emoting in closeup, often wet-eyed with yearning. Not many current actors who are known for self-effacing screen comedy can do this sort of thing well. Efron’s great at it.

Jackman is too old for his part—the age gap between him and Williams is especially jarring when Barnum confronts Charity’s moneybags daddy in the present about his cruelty to Barnum as a child, and the two actors are clearly about the same age—and some of the hair/hairpiece work is iffy (there’s one scene where Jackman seems to be wearing a hair yarmulke). But on the other hand, we’re at a point in film history where there’s only one star who’s good at this type of musical leading man role and has enough box office credibility from other projects (specifically his nearly 20-year run as Wolverine) to get an automatic green light for almost any new musical film merely by saying “Yes,” and his name happens to be Hugh Jackman—so I’d rather not nitpick him to death. He’s very likable as Barnum, even though the screenplay rarely characterizes the character as anything more than a nice guy who’s still battling some “respectability” issues left over from a tough childhood.

Jackman knows when not to wink. He really goes for it. This is the kind of film that includes a romantic comedy-styled, run-across-town-to-tell-the-leading-lady-something scene. Jackman, bless him, runs so hard that you’d think Barnum was rushing to defuse a bomb. Of course Barnum eventually finds his wife standing on a bluff overlooking a raging sea, staring Byronically out at the waves, back to the camera, hair and dress and indigo scarf blowing in the breeze. Barnum waits a moment before approaching her, as if reluctant to disturb such a gloriously cheesy image.