Taken simply on its own merits, “Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese” is certain to go down as one of the finest documentaries of the year. Following in the footsteps of Dylan and Scorsese’s previous collaboration, “No Direction Home: Bob Dylan,” the film is an eye-opening look at a brief but important chapter in Dylan’s personal and professional legacy—his wildly ambitious 1975 concert tour that found him performing shows in smaller venues, as the center of a ramshackle cast of performers and hangers-on that at times included the likes of Joan Baez, Ronee Blakely, Alan Ginsberg, Sam Shepard, Ronnie Hawkins, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, T-Bone Burnett and Patti Smith. Virtually from the moment the whole thing was conceived in the wake of Dylan’s massive 1974 comeback tour with The Band, the tour was shrouded in myth and mystery. But with its stunning archival material of thrilling concert performances and sometimes startling behind-the-scenes material, as coupled with new interviews that include Dylan himself in his first extended on-camera talk in more than a decade, “Rolling Thunder Revue” offers a revelatory glimpse of the subject that both hardcore Dylanologists and complete neophytes will find absolutely compelling.

“Rolling Thunder Revue” proves to be even more valuable as the latest addition to a small but fascinating canon of films that have served to complement Dylan’s groundbreaking work as a singer/songwriter. Factoring in how his songs are filled with dense imagery and allusions to classic films, along with his willingness to create and shed personas in the way an actor takes on different roles, Dylan’s musical life has long been informed by the world of cinema and throughout his career, he has used the tools of that particular medium to further pursue his artistic muse. At the same time, other filmmakers have sought to explore the singer’s ongoing legacy, and have sometimes even given him on-screen roles designed to make use of his undeniable presence, while others have based stories around the mythos that is conjured by the simple mentioning of his name.

Perhaps Dylan’s best-known cinematic endeavor—and certainly the one that’s had the biggest cultural impact—was his first, D.A. Pennebaker’s groundbreaking 1967 documentary “Don’t Look Back.” Shot over the course of three weeks in England in the spring of 1965, the film captures Dylan as he is preparing to shift from his acoustic, folk-based sound to full-blown rock ’n’ roll, a move that, as odd as it might seem today, would confound and outrage many of his fans. Instead of the hagiography that one might expect, Pennebaker offers an eye-opening look at Dylan as he goes through the motions of his tour, dealing with fans, the media, assorted hangers-on and even a couple of would-be Dylans with a combination of charm, cutting wit and outright arrogance that is fascinating to behold. At the same time, he cheerfully pokes holes in the persona that has been constructed for him as a noble, truth-telling protest poet while at the same time beginning to construct the one that he would fully adopt for the public in a few short months.

If nothing else, “Don’t Look Back” is jam-packed with a number of great scenes that would become celebrated moments in Dylan’s legacy. The opening sequence in which “Subterranean Homesick Blues” plays on the soundtrack while a bemused Dylan holds and discards a collection of cue cards featuring some of the lyrics—not only has this scene been endlessly parodied and homaged over the years by everyone from ESPN to “Weird Al” Yankovic to the 1992 political satire “Bob Roberts,” it essentially served as a basic prototype for what would become known as the music video. The scene in which Dylan patiently listens to folk singer Donovan croon one of his songs and then responds with a devastating rendition of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” is almost too cruel to watch. Although one’s attitude towards the version of Dylan seen here may vary depending on one’s age—what comes across as mere truth-telling at a younger age may come across as mere obnoxiousness a few years down the line—the impact of “Don’t Look Back” on both the documentary format in general and the Dylan myth in particular cannot be denied.

Dylan’s transition from acoustic to electric could be witnessed more fully in another 1967 film, “Festival,” an Oscar-nominated documentary on the Newport Film Festival that incorporated performances from the biggest names in folk shot during the 1963-1965 editions. Included is Dylan’s infamous 1965 set in which, after a couple of acoustic numbers, he played a few songs with an electric backup band that inspired a number of boos from the crowd, either because of the heresy of playing electric or because the sound system was so crummy that no one could hear anything.

From there, Dylan set to work on a film commissioned by ABC television that would document his 1966 U.K. tour backed by the Hawks, later to be known as The Band, that had been delayed in the wake of his motorcycle accident later that year. Once again, Pennebaker was hired to direct the film but after looking at Pennebaker’s cut, Dylan reportedly decided it was too similar to “Don’t Look Back” and elected to re-cut the film himself (with Kartemquin Films co-founder Gordon Quinn serving as one of the editors). When he finally showed his version, now known as “Eat the Document,” ABC swiftly rejected it for being too incomprehensible to broadcast. Although never officially released, it finally hit the bootleg circuit around 1972.

There are some fascinating moments to be had here and there—performances from the famous Manchester Free Trade Hall concert where an attendee yelled out “Judas,” a duet with Johnny Cash, and an alternately intriguing and depressing sequence in which a zoned-out Dylan and a seemingly equally addled John Lennon ride around in the back of a limousine—but the interesting stuff is padded out with a lot of what could politely be described as filler and even at a relatively brief 52 minutes, it feels much longer. Dylan fans in 1972 were better served with the release of “The Concert for Bangladesh,” a film commemorating a 1971 benefit concert that marked one of Dylan’s first public appearances after spending years out of the limelight and off the concert trail.

Although Dylan’s name had come up in casting discussions for a number of films over the years—there was a point when he was being thought of to co-star in “Bonnie & Clyde”—Dylan’s first acting role did not occur until 1973, when he was brought in by friend Kris Kristofferson to write the title song for the new film that he was working on, Sam Peckinpah’s “Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid.” The story goes that Peckinpah had never heard of Dylan or his music, but was taken enough by him to not only have him compose the entire score but play an actual on-screen role as Alias, a loner who ends up joining with Billy the Kid (Kristofferson) as he is being pursued by former friend and current lawman Pat Garrett (James Coburn) and, it is implied, will promote his legend after their fatal confrontation. The film had a legendarily troubled production that continued on even after filming stopped, and culminated with Peckinpah being pushed out after completing his cut and the studio reediting it into a bewildering mishmash that was disowned by practically everyone who worked on it. In 1988, however, Peckinpah’s version was discovered and released to great acclaim with many considering it one of the greatest Westerns ever made. (A couple of decades later, a third version would be cobbled together from the two previous iterations and a few heretofore unseen scenes.)

As for Dylan, his impact on the film is somewhat mixed. His character largely comes across like an afterthought, especially in the truncated version, and there are times when he seems just as bewildered by his presence as everyone else. That said, the raw charisma he demonstrated in “Don’t Look Back” is on full display here to the degree that whenever he’s on-screen, he winds up grabbing the focus of viewers, even though he is oftentimes just standing there doing nothing. Dylan’s musical contributions, on the other hand, were more duly celebrated—his score has a nice sonic match elegiac feel of the film and the lead song, a little ditty entitled “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” would go on to be one of his most enduring hits.

After going off on his mammoth 1974 comeback tour with The Band, Dylan began making plans for what would become the Rolling Thunder Revue and in addition to trying to arrange and stage such a complicated endeavor, Dylan chose to make things even more complicated by using it as a way of fully indulging in his dreams of working in film. The first project to emerge was simple enough—a concert film shot during one of the final shows from the tour that would be broadcast on television under the title of “Hard Rain.” Unlike “Don’t Look Back,” which was more interested in portraying the world that Dylan was living in at the time, “Hard Rain” is a straightforward performance film with nothing else to suggest the carnival-like atmosphere of the tour. As cinema, it isn’t much but as a concert recording, it gets the job done—although one can sense a certain amount of burnout among the players, the renditions of such then-current tunes as “Shelter from the Storm” and “Idiot Wind” are put forth with such ferocious energy that they come close to suggesting the then-developing punk rock sound.

Before long, however, it would become clear why “Hard Rain” was so slight in regards to everything other than performance—Dylan was putting together his own film, in which he would direct a loose narrative that would combine performance footage, behind-the-scenes interviews with the various participants and a number of dramatic scenes in which the various participants would pretty much improvise situations in front of the camera. (Although Dylan brought in Sam Shepard to help prepare a screenplay, Shepard is not credited in the finished film.) Using the classic film “Children of Paradise” as a clear thematic and structural inspiration, the film found Dylan himself dealing with the mythology that had grown around him, while at the same time grappling with the age-old question of male-female relationships. And like “Children of Paradise,” Dylan would recount his story of love and loss and thinly veiled autobiography (Dylan himself stars in the film, but the role of “Bob Dylan” is actually played by Ronnie Hawkins.) on a massive canvas, clocking in at just under four hours in length. Perhaps inevitably, when the film, “Renaldo and Clara,” finally emerged in early 1978, it received absolutely scathing reviews, even from the rock press, and had its release cut short after playing in only a couple of cities for a few weeks. So total was its failure, in fact, that to this day, the film has never been officially released in any home video format, though recordings made from a rare broadcast on British TV in the early 1980s can be found if you know where to look for them.

As perhaps the biggest white whale in Dylan’s entire artistic canon, “Renaldo and Clara” is a work that looms large in the mind of any Dylan fan. Though there are enough points of interest to make it worth considering even though most people, even Dylan fans, are likely to consider it unwatchable. The dramatic scenes are almost entirely a wash that are not even saved by the vaguely hinted and potentially intriguing notion that all the actors are playing variations of the same character—it does contain enough moments of intrigue to make it of interest to viewers who possess both a lot of patience and a willingness to sort through a lot of nonsense in order to get to the good stuff. The concert footage is uniformly excellent and not even Dylan’s odd decision to appear on stage wearing white face paint and even the occasional mask can entirely distract from thrilling renditions of tunes like “Tangled Up in Blue,” “Isis” and “Hurricane.”

The key problem seems to be that no one had any real idea of what the film was supposed to actually be in the first and when Dylan sat down to transform the reported 100 hours of footage that had been shot, his only hope at salvaging it was to adopt an aggressively non-linear format that might evoke memories of some of his more audacious musical moments. At a conventional running time, this approach might have actually worked but at four hours, it cannot help but come across as a largely formless mess. (Perhaps belatedly recognizing this, Dylan eventually put together a two-hour version of the film that was reportedly almost entirely comprised of musical performances, though this edition soon disappeared from view as well.)

Dylan would regain a little face, cinematically speaking, a little later in 1978 with the release of “The Last Waltz,” Martin Scorsese’s celebrated document of the final concert performance of The Band in which he turned up as one of a number of special guest performers. But that would be the last time that he would turn up on the big screen for the next decade or so. During this time, he did find himself occasionally working with name filmmakers on projects of wildly varying quality. To promote the release of his 1985 album Empire Burlesque, he brought in Paul Schrader, who was just coming off of “Mishima,” to direct a Tokyo-based video for the song “Tight Connection to My Heart,” which somehow got transformed into a borderline incomprehensible tale in which Dylan dresses like a refugee from a “Miami Vice” ripoff, simultaneously romances two women, is accused of murdering a yakuza member and occasionally remembering to lip-sync to the lyrics that have only a tenuous connection to the onscreen action.

The following year, Dylan worked with Gillian Armstrong on “Hard to Handle,” a straightforward concert video chronicling an early show from the much-anticipated tour he undertook with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. In 1990, he made a cameo appearance in a film directed by Dennis Hopper and alternately known as “Catchfire,” “Backtrack” or “That movie where Dylan turns up as a chainsaw sculptor and that isn’t the weirdest thing about it.”

And yet, even the Schrader video seems like a staid choice when compared to his first straightforward acting job since “Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid,” “Hearts of Fire.” Released in 1987, the drama told of an ambitious would-be singer (played by would-be pop star Fiona) finds herself torn romantically between the reclusive rock legend who becomes her mentor (guess who) and a current-day musical star (Rupert Everett). Despite the number of talented people involved with the project—the screenplay was co-written by Joe Eszterhas and it was directed by Richard Marquand, whose previous films had included the hits “Return of the Jedi” and “Jagged Edge” (and who passed away shortly its release)—the entire thing is so silly that it makes the later vehicles of Elvis Presley seem artistically sound by comparison. And yet, despite the absurdity of the whole thing (it is perhaps the one entry in the Dylan canon that comes closest to being outright camp) and perhaps in no small part to having no real competition from his co-stars, it’s Dylan who gives the proceedings the closest thing that it has to some kind of weight and focus.

Needless to say, it would be a long time before anyone dared to put Bob Dylan before a movie camera again. When it did happen, after a period in which he managed to reestablish himself both critically and commercially, and even won an Oscar for composing the song “Things Have Changed” for “Wonder Boys,” it not only found Dylan taking a significant creative position for the first time in a film since “Renaldo and Clara” but also directly engaging with his own considerable cultural legacy in ways that he had never attempted before. Collaborating with Larry Charles on a screenplay reportedly inspired heavily by notes scribbled by Dylan on scraps of paper over the years (and which they would credited pseudonymously), “Masked and Anonymous” (2003) was set in an unnamed land suggesting a banana republic version of the United States. Dylan plays Jack Fate, a once iconic and now nearly forgotten rock legend who, as the story opens, is bailed out of jail by an old friend (John Goodman) to play a televised benefit concert, though who exactly is benefitting from it is never entirely clear. While making his way to the show, Jack encounters a world gone increasingly wrong—one where chaos and conspiracy rule the day—while trying to come to grips with his own past and dealing with the litany of people who want to use and exploit him for his own ends. Appearing alongside Dylan was a startlingly deep all-star cast that included the likes of Jessica Lange, Jeff Bridges, Penelope Cruz, Mickey Rourke, Angela Bassett, Ed Harris and Luke Wilson, just to name a few.

Perhaps inevitably, when the film was released, it was slaughtered by critics with a ferocity that made their treatment of “Renaldo and Clara” seem nuanced by comparison, and rejected by audiences so harshly that it disappeared from theaters within a couple of weeks. But in their rush to dismiss the film as little more than a self-indulgent vanity project, critics failed to recognize that this work came closer than anything else to the qualities that made Dylan’s best songs so memorable—poetry, caustic wit, mistrust of authority in all forms, surrealistic flights of fancy and ambiguity—and translated them into cinematic terms. Like one of his classic songs, “Masked & Anonymous” takes audiences on a wild ride and is more interested in letting them come to their own conclusions as to what it all means, rather than telling them exactly what they are supposed to feel at any given point.

For students of Dylan, the film is a bounty of riches that finds him acknowledging his past while simultaneously refusing to allow himself to be defined by it, even at the risk of his own personal and professional freedom. Funny, strange, occasionally moving, sometimes shockingly prescient (the scene in which Mickey Rourke delivers a speech naming himself the new and unquestioned leader of the land certainly plays a lot differently today than it did just a few years ago) and filled with great music (with a soundtrack ranging from a collection of Dylan covers from around the world to several killer performances by Dylan and his real-life touring band), “Masked and Anonymous” is an absolute must-see for anyone with even the slightest interest in Dylan and his legacy, and a work ripe for rediscovery for anyone in the mood for something way off the beaten path.

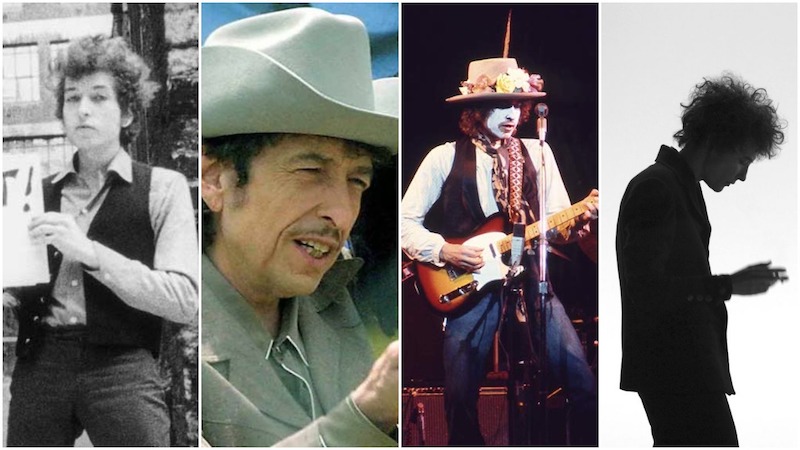

A few years later, writer/director Todd Haynes created a project that would also examine Dylan and his legacy, albeit in a format featuring no fewer than six different actors, including Christian Bale, Heath Ledger, Richard Gere, Ben Whishaw, Marcus Carl Franklin and Cate Blanchett (pictured above), representing him during key moments from his entire history, and in the service of a screenplay in which the name “Bob Dylan” would not be formally mentioned once outside of an opening caption declaring it to be “inspired by the music and many lives of Bob Dylan.” Between the casting gambit and a deliberately fractured narrative structure, “I’m Not There” (2007) may sound pretentious but the result is a startlingly beautiful and thoughtful work that is perhaps the most cogent and interesting artistic contemplation of Dylan’s life and work from an outsider to date. (Although Dylan signed off on the project, he made no other real contribution to it other than to supply an outtake of the title song to use on the soundtrack.)

Like “Masked and Anonymous,” Haynes and co-writer Owen Moverman approximated Dylan’s approach to songwriting by utilizing a densely packed collection of words and images that do not necessarily carry any single fixed meaning, and which will resonate in different ways with different viewers. Likewise, the mixing of the various eras may seem haphazard at first but the juxtapositions end up playing beautifully throughout. (Even the Western-themed fantasy section with Richard Gere, the portion most criticized at the time of its release, ends up paying off nicely, especially upon a second viewing.) The performances are also exciting throughout as well—while Blanchett deservedly received most of the accolades (including an Oscar nomination) for her evocation of the “Don’t Look Back”-era Dylan, Bale is equally strong in his representations of Dylan during his groundbreaking folly days and later during his evangelical period. Whether taken as historical fiction, cultural analysis, or as a wild cinematic trip, “I’m Not There” is a work as audacious and challenging as the person that it celebrates.

Offering a more straightforward look at Dylan’s life are the two epic-sized documentaries directed by Martin Scorsese, the first being 2005’s “No Direction Home: Bob Dylan,” which covers the period between his first arrival on the music scene in New York up to the point where he seemed to walk away from it all following his notorious motorcycle accident. “No Direction Home” originally began as a series of interviews conducted by Dylan’s manager, Jeff Rosen, with the likes of Joan Baez, Allan Ginsberg, Pete Seeger and even Dylan himself, who reportedly spoke on camera for over 10 hours (said to be Dylan’s only specific point of direct involvement with the film) and Scorsese was brought in later on to give shape to the massive collection of interviews and rarely seen archival material (including footage taken from the “Eat the Document” shoot) and turn it into a proper film. As the American filmmaker who had done the most to fuse the worlds of rock music and cinema together, Scorsese was the ideal choice to helm the project and what he has created is a compelling and personal work that never descends into mere hagiography. In charting Dylan’s initial ascension, he allows critiques about Dylan’s ambitions, his attitude and his occasional tendency to poach musical ideas, while at the same time showing how he grew and developed as an artist, sometimes to the chagrin of a public that wanted him to stay just as he was. “No Direction Home” is a masterful work of cultural biography, both in terms of popular music in general and Dylan in particular and deserves consideration as one of the best documentaries about a singer ever made.

And as good as “No Direction Home” is, “Rolling Thunder Revue” is arguably a better and more revealing work. Similar to “No Direction Home,” the film began with a series of interviews conducted by Rosen with many of the still surviving participants, including Dylan, Baez and the late Sam Shepard, and Scorsese was brought in to give the material, which included the footage shot by the multiple camera crews utilized by Dylan for “Renaldo and Clara,” a final form. It’s fascinating how “Rolling Thunder Revue” serves as a sort of redux of “Renaldo and Clara,” accentuating the stuff that worked in the original film (such as the still-stunning performance footage) while deleting the stuff that didn’t—namely the improvised dramatic sequences involving the romantic upheavals among the various characters—and replacing it with explorations of the real-life tensions that were going on in the background, ranging from the expected romantic boondoggles to the ways in which many of the players found themselves jockeying for positions in Dylan’s favor as the tour progressed.

In addition to serving as a sort of corrective to “Renaldo and Clara,” “Rolling Thunder Revue” offers up any number of priceless moments, some of which may even come as a surprise to ardent Dylan scholars—including electrifying footage of Patti Smith performing and conversing with Dylan, Joan Baez busting out a couple of unexpected dance moves to hilarious effect and, most bizarrely, the revelation that the white makeup Dylan wore onstage for most of the tour was apparently inspired in part by a conversation that he had with a 19-year-old Sharon Stone backstage about the KISS shirt she was wearing. And unlike the accompanying box set of musical performances from the tour, the film manages to somewhat convey the audacious scope of the entire enterprise. In the end, everyone admits that from a financial perspective, the Rolling Thunder Revue was a disaster that was just too big and weird for its own good. From an artistic point of view, however, “Rolling Thunder Revue” demonstrates that it was as unusual as its creator and that at its best, it hit peaks that are still astonishing to behold today.

So where does this leave Bob Dylan in cinematic terms? At this point, it is fairly unlikely that he is ever going to take another stab at acting, and there have only been rumors of movie projects based on songs like “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” and “Brownsville Girl.” On the documentary side, however, things are certainly more promising, as there are a number of periods of his career that could be reexamined in the same manner of “Don’t Look Back,” “No Direction Home,” and “Rolling Thunder Revue.” That said, Bob Dylan will always remain one of the most mysterious artists of the 20th century and beyond, and while there are no simple explanations for the man or his work, his cinematic output—as questionable as it has been at times in terms of quality—goes a long way to showing how he dealt with the questions raised by his work. Throughout these films, he remains the rarest of creatures in an era when no one seems to have secrets anymore—a genuine enigma.