In “The Annihilation of Fish,” age is the accumulation of scars. Aching memories, unhealed bruises and pent-up desires remain alive even when many of the sights and sounds that once decorated one’s existence are dormant. For James Earl Jones and Lynn Redgrave, two actors who were already in the autumn of their lives when the film was initially released a quarter century ago, age appears to have been an especially potent subject.

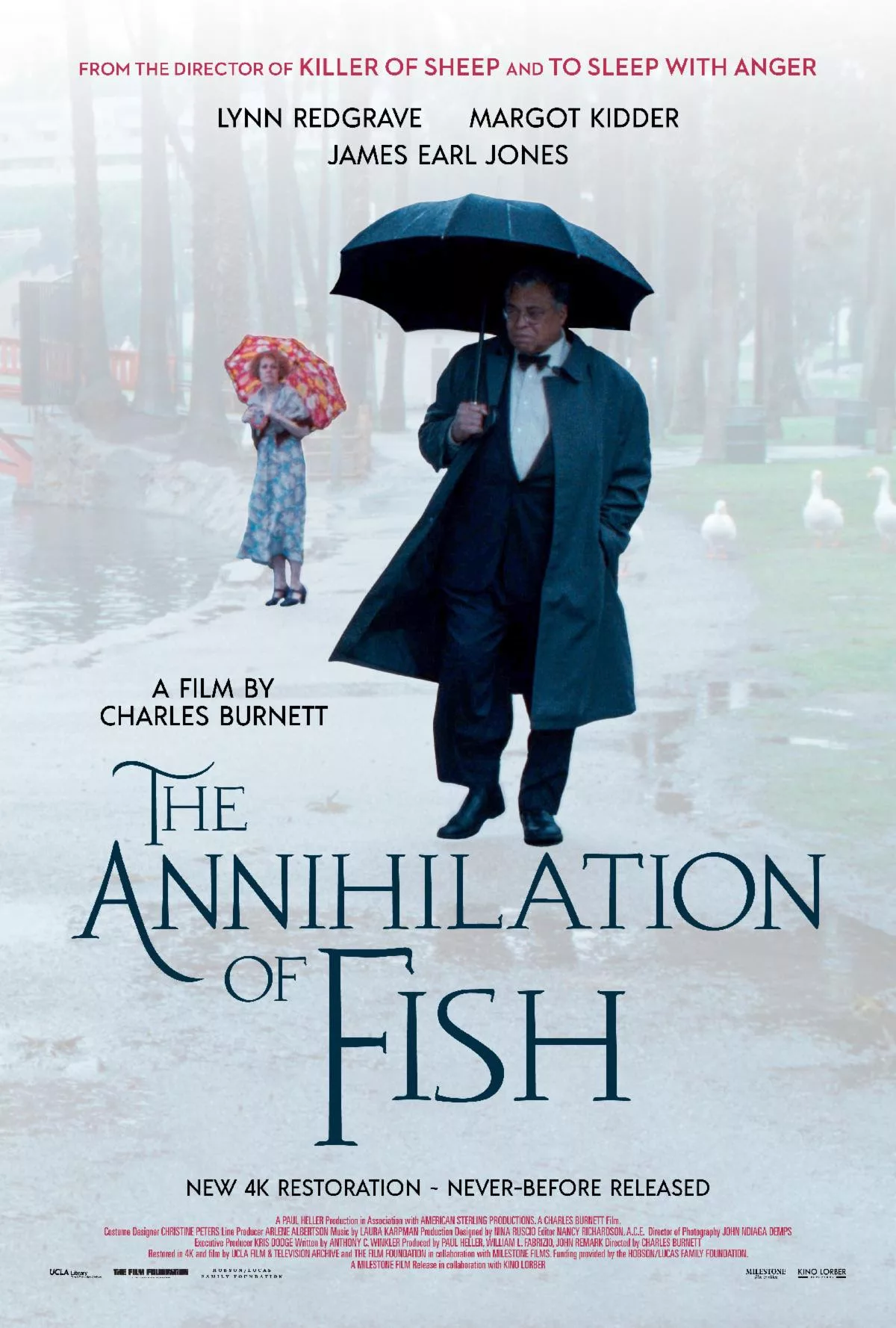

Jones and Redgrave portray Fish and Poinsettia, two lonely elderly individuals thrown together by chance, who are eventually rendered inseparable by their respective mental illnesses. The Jamaican-American Fish, recently released from a mental health hospital, literally wrestles with the demon inside his head. Poinsettia thinks she is in a relationship with the deceased Italian composer Giacomo Puccini. Fish and Poinsettia are put under one roof, in separate rooms, in a boarding house owned by the eccentric widow Mrs. Muldroone (Margot Kidder). With a script composed of odd apparitions and off-kilter characters—novelist Anthony C. Winkler wrote the screenplay—in a lesser director’s hands, these three characters would devolve into glib elderly stereotypes and othered humor. In Charles Burnett’s direction, they possess a humanizing gentleness that invites big laughs but never smug derision.

When “The Annihilation of Fish” premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2001, it struggled to gain footing—ultimately being shelved by distributors after a lone negative review. Only recently, through the efforts of Milestone Films and Kino Lorber, whose 4K restoration was carried out by UCLA Film & Television Archive and The Film Foundation and funded by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation, has the film become widely available again—screening as the closing night film at the Black Harvest Film Festival in late 2024 and now being re-released in theaters for an overdue reappraisal.

Within the first five minutes of “The Annihilation of Fish,” it’s not only clear that a great wrong has been righted. It’s also obvious this film is the essence of what makes Burnett’s hold on the American mythos peerless and exceptional.

At every turn, “The Annihilation of Fish” is wonderfully surprising. Consider how we first meet Fish. He is attending church. Common features surround him: The passionate preacher, the coordinated choir and the humming parishioners. But then Fish suddenly and violently falls back onto the floor, knocking over a woman in the process. Did the holy spirit touch him? Quite the opposite. For ten years, since he retired from cleaning bus terminals, a demon, as Fish believes, has wanted to fight him. That belief landed Fish in a mental health hospital. A recent change in the law is now setting him free; he travels from New York City to Los Angeles where he takes up residence with Mrs. Muldroone, who will allow any slight made against her except anyone forgetting the “e” at the end of her name.

Mrs. Muldroone never questions Fish’s behavior. He holds no vices and promises to always spell her name accurately, which is good enough for her. Mrs. Muldroone encourages Fish’s physical activity, believing his wrestling with a demon to be good exercise. She is equally accepting of Poinsettia; she left San Francisco after realizing that no one will officiate a marriage between herself and the ghost of Puccini. Other than believing a ghost to be her lover, Poinsettia’s worst attribute is “operatically” singing off-key to the deceased opera singer—a wrinkle the kindhearted Mrs. Muldroone can mostly tolerate. Poinsettia’s second worst habit is getting plastered at the bar then falling asleep in the hallway outside of Fish’s door. Fish takes pity on Poinsettia, pulling her into his apartment and tucking her in on his couch.

Fish isn’t unaware of the racial connotations behind his charitable deed. When Poinsettia first awakens on his couch, for instance, she doesn’t just understandably wonder what happened the night before. She throws barbs at Fish wrapped in clearly racist overtones, often calling Fish a “Jamaican bastard” and reporting to Mrs. Muldroone—who she hopes shares her white fragility—that a Black man may have taken advantage of her. If it weren’t for the sizable chemistry shared by Jones and Redgrave you could imagine how Burnett’s film might easily devolve into trite racial healing or flat animosity. Instead, Jones and Redgrave, through Burnett’s signature touch of off-kilter humor, make a joke out of their interracial pairing. “In Jamaica, a white woman would only be fed bread and water for a week if she kissed a Black man,” quips Fish. “I like my women chunkier,” he further chides to signal some disinterest.

Both Jones and Redgrave are exceptional. Fish requires an intense, physical performance by Jones, who by this point was 68 years old. When in conversation or walking through the world, his posture is stiff, dignified even. When he’s wrestling the demon—Burnett and his DPs switch to a woozy demon POV shot for these scenes—he’s hunched, sweaty and burly but not without grace. Redgrave, on the other hand, practices a different kind of physicality. Her lithe body seems to shimmer; she is agitated and fussy, her hands and eyes moving nervously as she readjusts her figure. Neither is quite sure what the other is about. But the whiff of a new energy, of a distinct kindness born from years of loneliness pull them, hesitantly, toward each other.

“What do we have in common,” asks Fish. “We’re old,” responds Poinsettia.

While that much is true, we can also surmise that Fish and Poinsettia share much more. The past still afflicts them. The memory of his wife still afflicts Fish; Poinsettia carries the scars of domestic abuse. Even Mrs. Muldroone, who waters a weed in her expansive garden daily, because it reminds her of her husband—and not in a good way—still holds some baggage. It’s telling that, despite the film being set in the new millennium, the interiors of this Victorian house, from the floral wallpaper to its mid-century appliances and furniture, appears to be stuck in another time. Each character, in their own way, hasn’t mentally left the temporal site of their trauma. Most of the time that fact is evident. In others, particularly the case of Mrs. Muldroone, that reality isn’t totally plain. Kidder painstakingly keeps that side hidden, expertly revealing the fractured parts of her character when necessary, providing a quiet comedic performance in the face of these two big personalities.

The other component that tightly binds this trio is the subject of mental health. While Burnett pokes some fun at these delusions, he doesn’t punch down. In fact, he doesn’t even confirm these visions as delusions. Similar to “To Sleep with Anger,” a film that features a possible demonic figure arriving from the South to visit old friends in Los Angeles, Burnett allows superstition and mysticism to take over. In “The Annihilation of Fish” there is, of course, the demon vision, which causes the camera to show some legibility of the demon’s existence. Whenever Fish drops the demon out of the window into the bushes, the shrubs also shake. And although Poinsettia doesn’t see the apparition, she too comes to believe in its reality.

That playfulness with spirits is born from Burnett’s southern roots, where folktales and oral stories are a prominent way of life. Maybe that is why Burnett’s films have always been misunderstood in their time; he is always shifting the southern gothic milieu into urban centers like Los Angeles—putting his characters in conversation with an American lore that stretches from Flannery O’Connor to O. Henry. That translation of southern tradition to northern city centers, where Southern Black people became fishes out of water—and in this case, there is also the transfer of West Indian beliefs onto the American landscape—matches the journey of the great migration that has always stood as the backbone of Burnett’s unmatched ability to sincerely tell the diverse story of the Black diaspora.

It’s also his insistence on capturing seemingly rudderless people—the people that time, social services, and the economy have left behind—that Burnett has carried with him from “Killer of Sheep” to here. Fish and Poinsettia don’t invest in juicy subplots or tasteless rivalries, but they aren’t without desires or dreams, interior or depth. They are humans who fulfill the greatest miracle a human can fulfill; they see one another fully as themselves and without reservation. “The Annihilation of Fish,” therefore, isn’t so much a reckoning, as it is radical recognition.

Opens 2/14 in NYC and 2/20 in Los Angeles.