Bob Dylan idolatry is one of the enduring secular religions of our day. Those who worship him are inexhaustible in their fervor, and every enigmatic syllable of the great poet is cherished and analyzed as if somehow he conceals profound truths in his lyrics, and if we could only decrypt them, they would be the solution to–I dunno, maybe everything.

In “Masked and Anonymous,” where he plays a legendary troubadour named (I fear) Jack Fate, a religious fanatic played by Penelope Cruz says: “I love his songs because they are not precise–they are completely open to interpretation.” She makes this statement to characters dressed as Gandhi and the pope, but lacks the courtesy to add, “But, hey, guys, what do you think?” I have always felt it ungenerous to have the answer but wrap it in enigmas. When Woody Guthrie, the great man’s inspiration, sings a song, you know what it is about. Perhaps Dylan’s genius is to take simple ideas and make them impenetrable. Since he cannot really sing, there is the assumption that he cannot be performing to entertain us, and that therefore there must be a deeper purpose. The instructive documentary “The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack” suggests that it was Ramblin’ Jack Elliott who was the true follower of Woody, and that after he introduced Dylan to Guthrie, he was dropped from the picture as Dylan studiously repackaged the Guthrie genius in 1960s trappings.

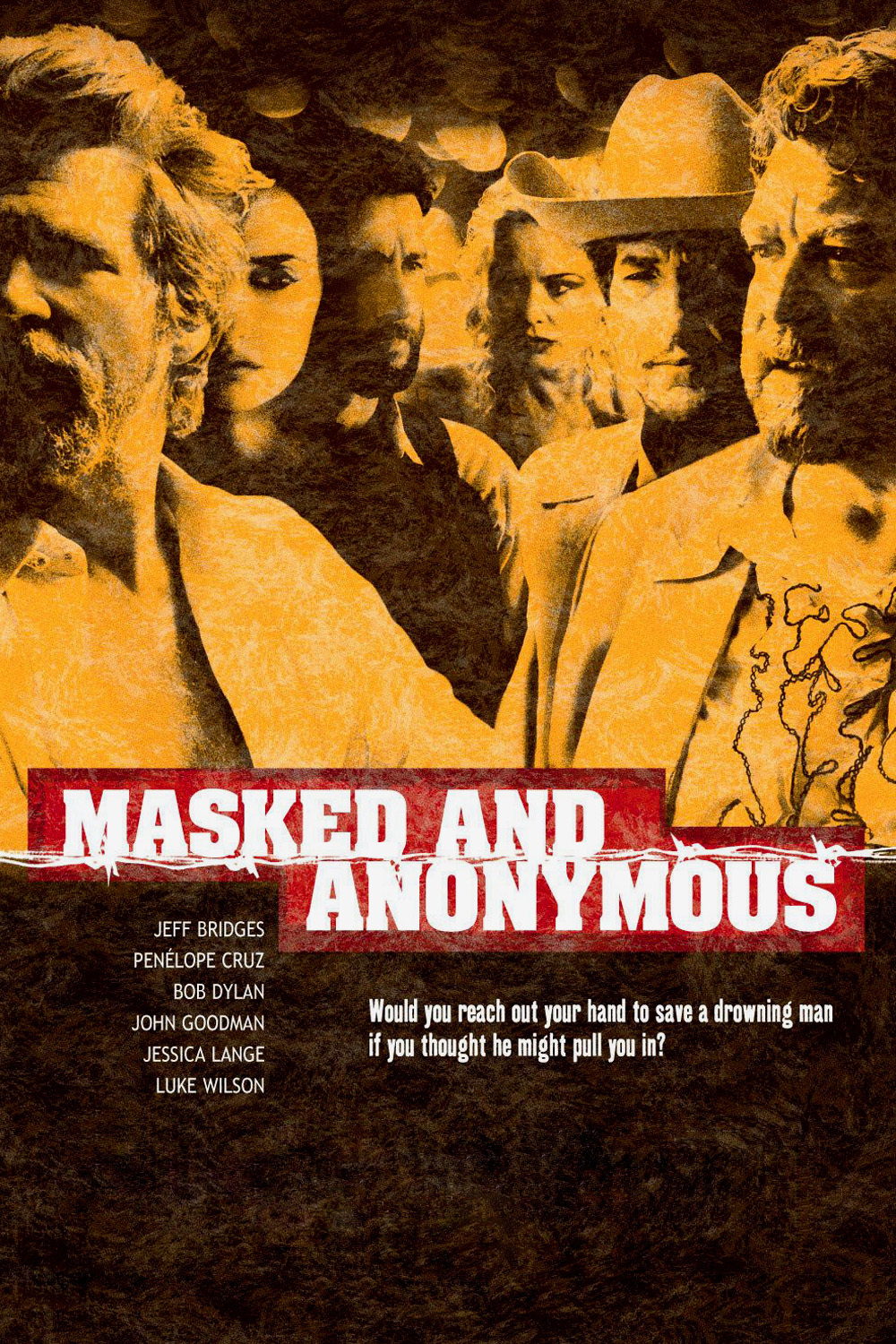

That Dylan still exerts a mystical appeal, there can be no doubt. When “Masked and Anonymous” premiered at Sundance 2003, there was a standing ovation when the poet entered the room. People continued to stand during the film, in order to leave, and the auditorium was half empty when the closing credits played to thoughtful silence. One of the more poignant moments in Sundance history then followed, as director Larry Charles stood on the stage with various cast members, asking for questions and then asking, “Aren’t there any questions?” The movie’s cast is a tribute to Dylan’s charisma. Here are the credits after Dylan: Jeff Bridges, Penelope Cruz, John Goodman, Jessica Lange, Luke Wilson, Angela Bassett, Steven Bauer, Michael Paul Chan, Bruce Dern, Laura Elena Harring, Ed Harris, Val Kilmer, Cheech Marin, Chris Penn, Giovanni Ribisi, Mickey Rourke, Richard Sarafian, Christian Slater, Fred Ward, Robert Wisdom. In a film where salaries must have been laughable, these people must have thought it would be cool to be in a Dylan movie. Some of them exude the aw-shucks gratitude of a visiting singer beckoned onstage at the Grand Ole Opry. Ironically, the credits do not name the one performer in the movie whose performance actually was applauded; that was a young black girl named Tinashe Kachingwe, who sings “The Times They Are A-Changin’ ” with such sweetness and conviction that she is like a master class.

The plot involves a nation in the throes of post-revolutionary chaos. This is “a ravaged Latin American country” (Variety) or perhaps “a sideways allegory about an alternative America” (Salon). It was filmed in run-down areas of Los Angeles, nudge, nudge. A venal rock promoter named Uncle Sweetheart (Goodman) and his brassy partner, Nina Veronica (Lange), decide to spring Jack Fate from prison to give a benefit concert to raise funds for poverty relief (maybe) and Uncle and Nina (certainly). That provides the pretense for Dylan to sing several songs, although the one I liked best, “Dixie,” seemed a strange choice for a concert in a republic that, wherever it is, looks in little sympathy with the land of cotton.

The enormous cast wanders bewildered through shapeless scenes. Some seem to be improvising, and Goodman and Bridges (as a rock journalist) at least have high energy and make a game try. Others look like people who were asked to choose their clothing earlier in the day at the costume department; the Happenings of the 1960s come to mind.

Dylan occupies this scenario wearing a couple of costumes borrowed from the Tinhorn Dictator rack. Alarmingly thin, he sprawls in chairs in postures that a merciful cinematographer would have talked him out of. While all about him are acting their heads off, he never speaks more than one sentence at a time, and his remarks uncannily evoke the language and philosophy of Chinese fortune cookies.

“Masked and Anonymous” is a vanity production beyond all reason. I am not sure, however, than the vanity is Dylan’s. I don’t have any idea what to think about him. He has so long since disappeared into his persona that there is little received sense of the person there. The vanity belongs perhaps to those who flattered their own by working with him, by assuming (in the face of all they had learned during hard days of honest labor on a multitude of pictures) that his genius would somehow redeem a screenplay that could never have seemed other than what it was, incoherent raving juvenile meanderings. If I had been asked to serve as consultant on this picture, my advice would have amounted to three words: more Tinashe Kachingwe.