Duke Johnson is a visionary filmmaker who understands the pliability of the cinematic image, as evidenced primarily in his work with Charlie Kaufman on the Oscar-nominated “Anomalisa.” (He also worked on 2020’s breathtaking “I’m Thinking of Ending Things”). Johnson brings his vision to his first solo full-length live-action project, an unexpected adaptation of Donald Westlake’s novel Memory, which was written in the ‘60s but published in 2010.

Turning that story of an amnesiac actor into a surreal study of identity proves something of a challenge for Johnson. However, the always-stellar André Holland once again adds so much to a production, imbuing every scene with a deep vein of melancholy. Imagine being sad and not being sure why because your sense of place in the world has been shattered. “The Actor” sometimes falls victim to the truth that no one is as interested in the dream you had last night as you are—it struggles to keep engaged with its ideas through a draggy midsection. But it’s an undeniably haunting piece of work, a story that’s out of place and time in a world that’s like our own but not quite. Rod Serling would have dug it.

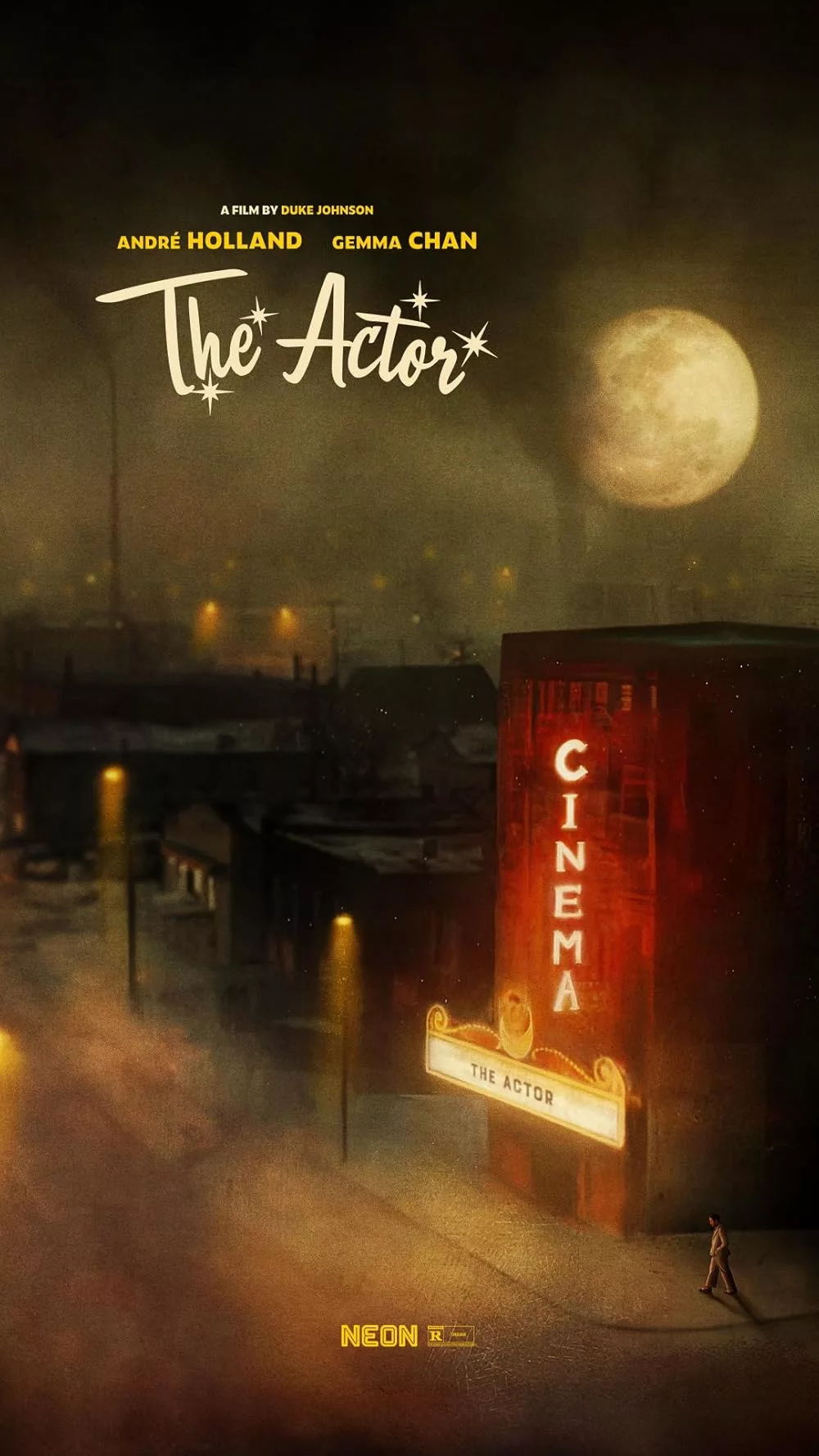

Holland plays Paul Cole, who is seen in the opening moments being assaulted by a man who has found Paul with his wife, although even this encounter is shot like it’s happening on a stage instead of in reality. Paul was in a traveling production, which means when he wakes, he’s stranded far from home with little sense of who he was before the attack. Stuck in the Midwest without the money even for a train ticket, he gets a job at a tannery to afford food and lodging before he can even consider transportation home. From the beginning, Johnson is playing Lynchian tricks, having different characters played by the same performers, including Toby Jones and Tracey Ullman, but Gemma Chan is the one who catches Paul’s eye in a movie theater. She seems to be the only one who truly sees him.

These early scenes of palpable confusion being pierced by instant attraction give way to an over-long mid-section when Paul gets back to New York City to discover he may not honestly want to discover who he used to be. A scene in which his friends recount a moment of alleged humor involving an unhoused person that Paul identifies as cruelty is a crucial one. It’s not just a question of who Paul was, but what kind of person Paul was before he wiped his personality clean. Could this incident be a chance to start over, remaking Paul into a better person than the one before? Could it give Paul a new role to play in life?

“The Actor” was reportedly filmed on a sound stage in Budapest, and that enhances the film’s very intentionally dreamlike quality, both in Joe Pasarelli’s gauzy cinematography and the theatrical production design, one that seems to take to heart the idea that all the world’s a stage. Holland vividly captures a man trying to get a grip on reality, but Johnson, as he did in “Anomalisa,” seems to be asking what that even means, especially for someone who has made a living shifting his identity to fit a new part. What if this is just an opportunity to become the character in real life that he was always meant to play anyway?

Clearly, “The Actor” is a film rich with ideas, and I sometimes wished for a firmer directorial hand in wrangling those ideas into something more fluid. Scenes have a habit of ending abruptly, and themes feel discarded before they can be fully explored. Again, it’s almost like a dream, which makes for a lack of consistent momentum.

Thank God for Holland, who carries this film on his expressive shoulders. There’s a scene near the end in which he’s just conveying different emotions into the mirror, trying to find the one that fits, and even here, Holland makes subtle choices. He always does. Because of that subtlety, “The Actor” lingers like smoke in the air long after it’s over.