An odd thought occurred to me a few hours after I saw writer/director Wes Anderson‘s “The Grand Budapest Hotel” for the first time. It was that Anderson would be the ideal director for a film of “Lolita,” or a mini-series of “Ada.” Now I know that “Lolita” has been filmed, twice, but the fundamental problem with each version has nothing to do with ability to depict or handle risky content but with a fundamental misapprehension that Nabokov’s famous novel took place in the “real world.” For all the authentic horror and tragedy of its story, it does not. “I am thinking of aurochs and angels, the secret of durable pigments, prophetic sonnets, the refuge of art,” Humbert Humbert, the book’s monstrous protagonist/narrator, writes at the end of “Lolita.” Nabokov created Humbert so Humbert might create his own world (with a combination of detail both geographically verifiable and stealthily fanciful), a refuge from his own wrongdoing.

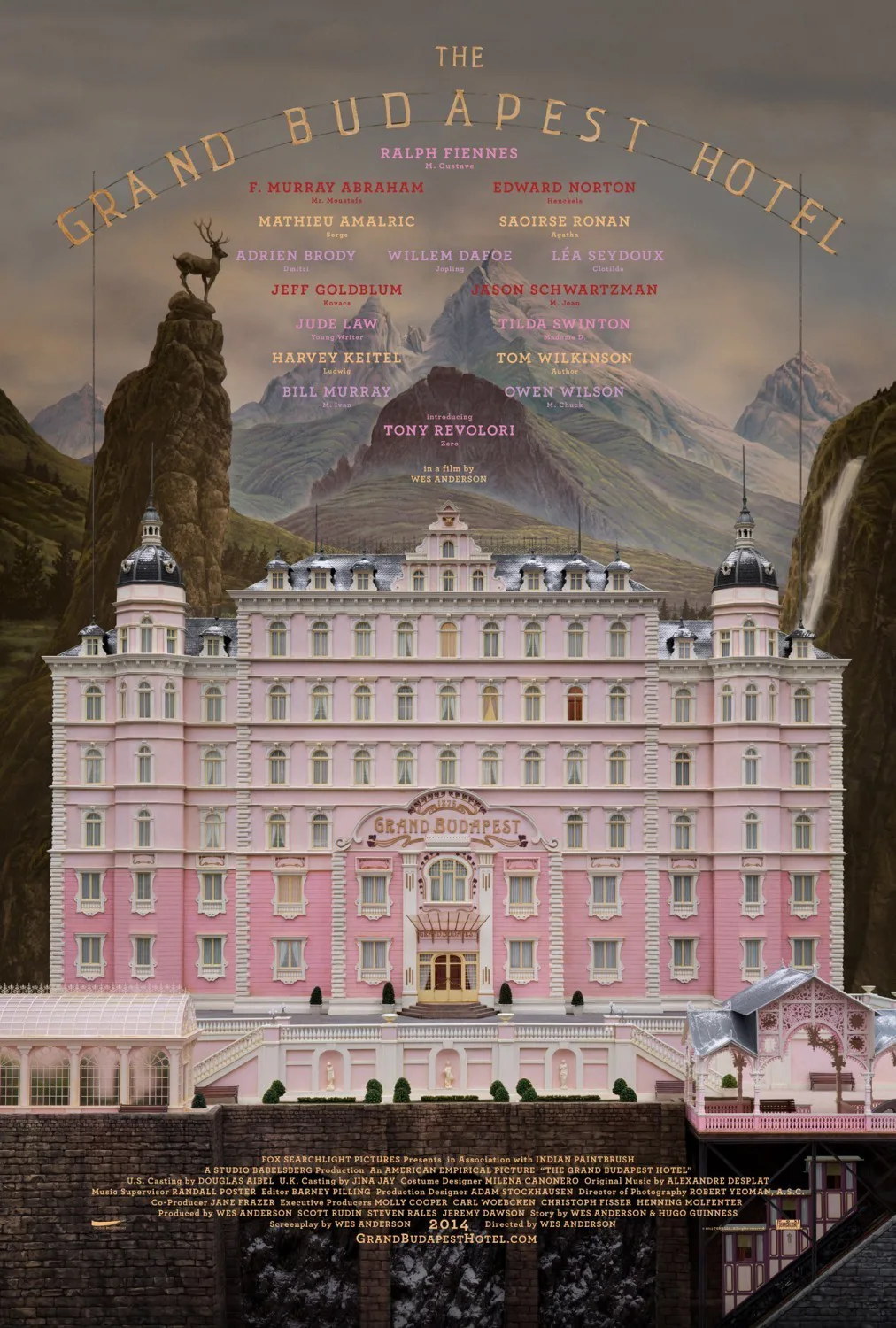

“The Grand Budapest Hotel” uses a not dissimilar narrative stratagem, a nesting-doll contrivance conveyed in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-a-crucial-part-of-it opening. A young lady visits a park and gazes at a bust of a beloved “Author,” who is then made flesh in the person of Tom Wilkinson, who then recalls his younger self in the person of Jude Law, who then recounts his meeting with Mr. Moustafa (F. Murray Abraham), the owner of the title hotel. Said hotel is a legendary edifice falling into obsolescence, and Law’s “Author” is curious as to why the immensely wealthy Moustafa chooses to bunk in a practically closet-size room on his yearly visits to the place. Over dinner. Moustafa deigns to satisfy the writer’s curiosity, telling him of his apprenticeship under the hotel’s one-time concierge, M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes).

All of this material is conveyed not just in the standard Wes Anderson style, e.g., meticulously composed and designed shots with precise and very constricted camera movements. In “Hotel” Anderson’s refinement of his particular moviemaking mode is so distinct that his debut feature, the hardly unstylized “Bottle Rocket,” looks like a Cassavetes picture by comparison. So, to answer some folks who claim to enjoy Anderson’s movies while also grousing that they wish he would apply his cinematic talents in a “different” mode: no, this isn’t the movie in which he does what you think you want, whatever that is.

What he does is his own thing, which in terms of achievement is on a similar level of difficulty to what Nabokov kept upping the ante on in his English-language novels: to conjure poignancy and tragedy in the context of realms spun off from but also fancifully, madly removed from dirt-under-your-fingernails “reality.” M. Gustave is a didact of high-level service, schooling young Zero Moustafa in the art of understanding what a guest wants, and getting it to the guest, before the guest has even thought of it. He wears a scent called “Eau de Panache.” He’s also a ludicrous horndog and gigolo, and his troubles begin when the wealthiest of his dowagers (Tilda Swinton) dies and leaves him a strange painting. The dowager’s impossibly evil son (Adrian Brody) wishes M. Gustave to get nothing, and will stop at nothing to see to that. His determination sets into motion a series of intimidations and assaults that’s complicated by the rise of an ostensibly Fascist power in the often-candy-colored Middle-Europe Bohemian Theme Park Anderson and his production designers conjure up here. (Since I’ve invoked Nabokov twice in this review, I really ought to emphasize that the movie itself credits the writings of Stefan Zweig, the Austrian writer whose wry, poignant autobiography was titled “The World of Yesterday,” as a primary inspiration.)

The dialogue is contemporary American, with plenty of cursing; the action is often grisly slapstick, with an upping of the imperiled-animal quotient that provided one of the more disquieting scenes of Anderson’s last feature, “Moonrise Kingdom.” The references are multitudinous, and come from everywhere (one of my favorites is a cable car sequence nodding to Carol Reed’s 1940 thriller “Night Train To Munich”). The cast is the usual top-to-bottom array of incredible talent, including, aside from the aforementioned, Matthew Amalric, Willem Dafoe, Jeff Goldblum, Harvey Keitel, Edward Norton, Saoirse Ronan, Léa Seydoux, and Anderson stalwarts Bill Murray, Jason Schwartzman, and Owen Wilson. (Newcomer Tony Revolori plays the young Moustafa.) The settings include not just the hotel but also a dank prison, a heavenly bakeshop, and all manner of horse drawn or steam-driven conveyances.

Although it’s packed with incident, there’s a stillness to the film that makes looking at it feel as if you’re staring at a zoetrope image of a snow globe, while at the same time a stray epithet here or the spectacle of some severed digits there pulls in a different direction, suggesting Anderson’s conjured world is subject to tensions that exist entirely outside of it, calling attention to that which is unseen on the screen: an anxious creator who wants everything just so, but can’t control the intrusion of vulgarity or cruelty. This tension is reflected in the character of M. Gustave himself, whose air of refinement masks a boyish exuberance and vulgarity, and who is nevertheless revealed at the movie’s end to be a human being of absolute nobility.

As much as “The Grand Budapest Hotel” takes on the aspect of a cinematic confection, it does so to grapple with the very raw and, yes, real stuff of humanity from an unusual but highly illuminating angle. “The Grand Budapest Hotel” is a movie about the masks we conjure to suit our aspirations, and the cost of keeping up appearances. “He certainly maintained the illusion with remarkable grace,” one character remarks admiringly of another near the end of the movie. “The Grand Budapest Hotel” suggests that sometimes, as a species, that’s the best we can do. Anderson the illusion-maker is more than graceful, he’s dazzling, and with this movie he’s created an art-refuge that consoles and commiserates. It’s an illusion, but it’s not a lie.