Wes Anderson‘s mind must be an exciting place for a story idea to be born. It immediately becomes more than a series of events and is transformed into a world with its own rules, in which everything is driven by emotions and desires as convincing as they are magical. “Moonrise Kingdom” creates such a world and takes place on an island that might as well be ruled by Prospero. It’s set in 1965, though it might as well be set at any time.

On this island no one seems to live except for those involved in the story. There is a lighthouse in which the heroine, Suzy, lives with her family, and a Scout camp where the hero, Sam, stirs restlessly under what seem to him childish restrictions. Sam and Suzy met the previous summer and have been pen pals ever since, plotting a sort of jailbreak from their lives during which they could have an adventure out from under the thumbs of adults, if only for a week.

Sam (Jared Gilman) is an orphan, solemn behind oversized eyeglasses, an expert in scouting. Suzy (Kara Hayward) is bookish, a dreamer. When they have their long-planned secret rendezvous in a meadow on the island, Sam is burdened with all the camping and survival gear they will possibly need, and Suzy has provided for herself some books to read, her kitten and a portable 45 rpm record player with extra batteries.

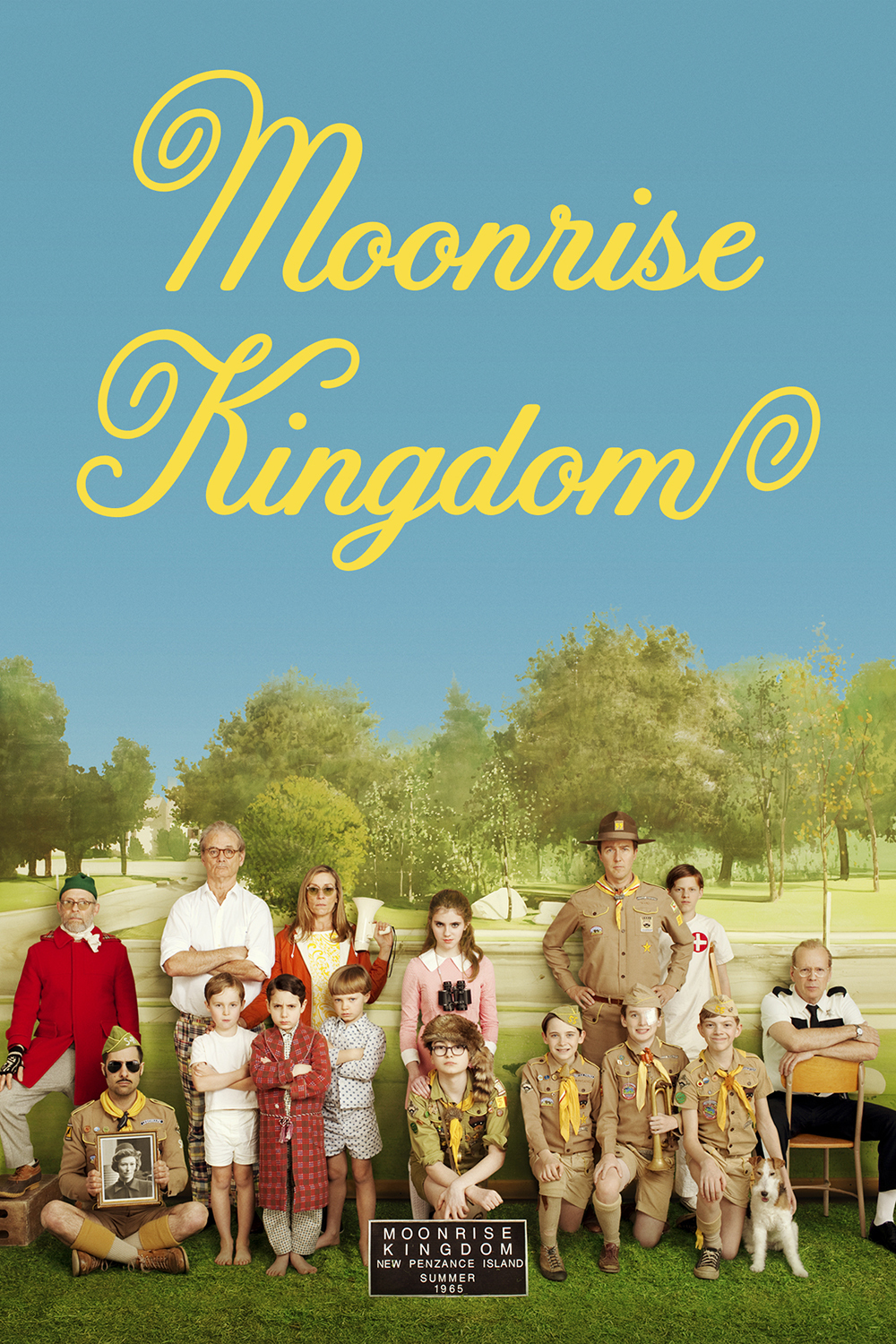

Because this is a Wes Anderson film, you know Bill Murray will appear in it. He has worked in the last five of Anderson’s six films. In “Moonrise Kingdom,” he plays Walt Bishop, Suzy’s father, and Frances McDormand is her mother. Murray is always right for a role in an Anderson film, and I wonder if it’s because they share a bemused sadness. You can’t easily imagine Murray playing a manic or a cut-up; his eyes, which have always been old eyes, look upon the world and waver between concern and disappointment. In Anderson’s films, there is a sort of resignation to the underlying melancholy of the world; he is the only American director I can think of whose work reflects the Japanese concept mono no aware, which describes a wistfulness about the transience of things. Even Sam and Suzy, sharing the experience of a lifetime, seem aware that this will be their last summer for such an adventure. Next year they will be too old for such irresponsibility.

It is not a large island, but they think it must have a place where they can hide out. Sam has come prepared with maps for their trek, and they follow an old Indian trail to a secluded cove which they name Moonrise Kingdom. Here they make their camp, which a Scout leader is later to tell Sam is “the best-pitched camp I have ever seen.” And here, as they sit side by side and look out over the water, in a sense they regard the passage of innocence and the disturbing possibility of maturity.

Meanwhile, the adult world has launched a worried search for them. Suzy’s parents call in the police, led by Capt. Sharp (Bruce Willis). Scoutmaster Ward (Edward Norton) leads Sam’s fellow Scouts, who were not terrifically fond of the way he seemed to take the troop with less than utter dedication. A character known only as Social Services (Tilda Swinton) gets involved, because as an orphan, Sam is of special interest.

Anderson always fills his films with colors, never garish but usually definite and active. In “Moonrise Kingdom,” the palette tends toward the green of new grass, and the Scout’s khaki brown. Also the right amount of red. It is a comfortable canvas to look at, so pretty that it helps establish the feeling of magical realism.

The approaching turmoil of adolescence is foretold, however, by an approaching hurricane that places the lives of the young explorers in danger. Their trek, their camp and the search for them under the mounting danger reminds me of the sort of serials I used to follow in Boy’s Life magazine, although those regrettably were not co-ed.

The success of “Moonrise Kingdom” depends on its understated gravity. None of the actors ever play for laughs or put sardonic spins on their material. We don’t feel they’re kidding. Yes, we know these events are less than likely, and the film’s entire world is fantastical. But what happens in a fantasy can be more involving than what happens in life, and thank goodness for that.