Projects that primarily center on characters’ isolation and the respite they experience from hiding themselves behind a screen land differently in the post-lockdown era. Director Albert Birney’s “OBEX,” though set in 1987 (denoted as such by TV adverts for “Nightmare on Elm Street”), feels seeped with such proximate anxieties. It is sympathetic to the ways we’ll migrate to digital worlds to escape the hell of embodied living, but it sweetly and gently reminds us about the beautiful inconvenience of community. Even though we can pick our flavor of digital numbing, Birney brings his DIY mentality and a host of collaborators who are in sync with his sensibilities to craft a project that shakes us out of the tempting lull and urges us to live life as an NPC.

The first section of “Obex” focuses on the daily rhythms of its protagonist, Conor Marsh (Birney), who lives in his Maryland house with his dog, Sandy (played by Dorothy, who gives fellow horror hound Indy from “Good Boy” a run for his money). His only communication with the outside world is with his neighbor and proto-DoorDash driver, Mary (Callie Hernandez), who kindly delivers him food but is never invited into his home. We spend much of the film watching Conor and Sandy go about their lives in an unremarkable fashion; Birney plays Conor with relatable contentment. He has his dog and three TVs … what’s there not to like?

Mileage may vary about whether or not you enjoy getting what amounts to an extended house tour, but Birney and his crew have put in the work to make Conor’s house the type of oasis that would warrant such sedentary. The production value is rendered in such hypnotic detail that I found it a joy to simply be lost in the lo-fi, analog space. It is befitting of the theme, in that Conor has created his home to be a place of such alluring safety and comfort that it becomes nauseating to consider leaving (or any form of disruption).

Pete Ohs (who most recently directed quirky nightmares of his own with last year’s “The True Beauty of Being Bitten by a Tick” and “Erupcja”) serves as the cinematographer and co-writer, and the film thrives on his and Birney’s surreal wavelength. Even though Conor is comfortable, the film’s visual language is anything but. We often see Sandy and Conor framed from an object in Conor’s room; as we peek at their lives from the perspective of a toaster or keyboard, these grainy shots, dreamy in their ambling compositions, feel as though they’re probing for dysfunction. It feels like we’re seeing Conor’s and Sandy’s lives from the perspective of a benevolent spirit, watching and curious about how someone seemingly well-adjusted can be so lonely. It feels less like a movie we stumbled upon and shouldn’t be seeing, and more like a project that’s eerily being filmed, where we’re trying (and failing) to locate the cinematographer.

The sound design is worth saluting, as Kevin Hill, the re-recording mixer, and Matthew Giordano, the post-production sound designer, work to create a hypnotic soundscape that chillingly unites disparate elements. Josh Dibb’s score, with its spectral and techno-piercing wavelengths, is unsettling in and of itself, and it’s particularly fascinating to see them work in the context of the rest of the film’s audio. The buzzing of cicadas outside Conor’s home is a common audio fixture, but it gets remixed with the hissing of the tea kettle in Conor’s kitchen, the hum of TV static, and the downpour of a running faucet, so that these sounds become indistinguishable from one another. Try as he might, Conor’s digital life is bleeding into his physical one.

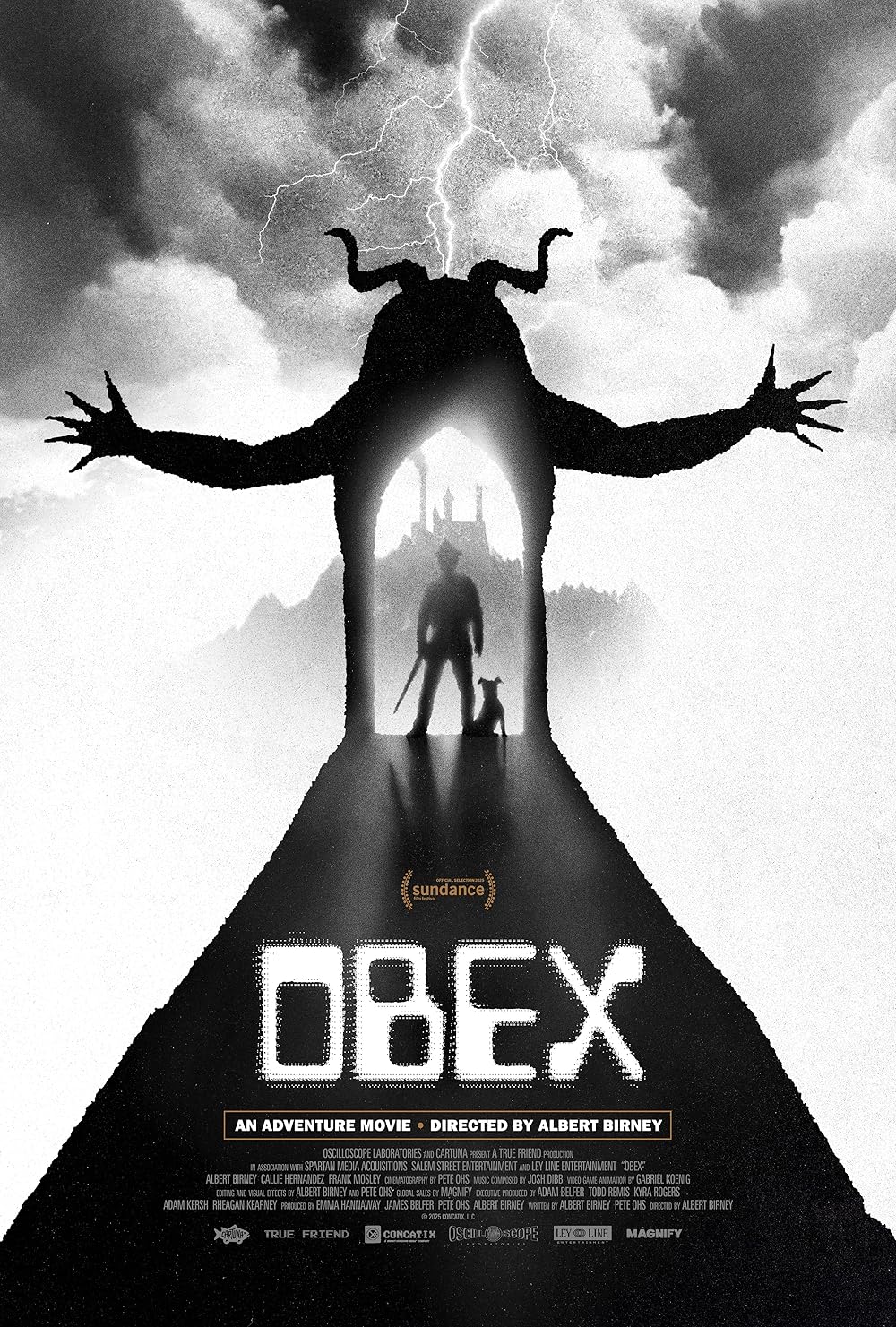

That theme comes more into the fray after the film’s inciting crisis. Conor later sees an ad for the mysterious, state-of-the-art computer game, OBEX, which allows you to scan yourself into the game, where you have to fight the demon king, Ixaroth. Conor plays the game but quickly gets bored, and later finds that Sandy has been abducted by Ixaroth. He then reenters the game to liberate Sandy from her digital captor, all the while being forced to grapple with the uncomfortable truths about his family history and how that trauma informed his tendency to self-isolate.

The world of OBEX, while free of keyboards and printers, is just as painstakingly realized as Conor’s physical world. There, he meets Mary in real life (Hernandez, riparian in her ability to oscillate between earnest and farcical, is a delight even in her small scenes) and encounters a traveling companion with a TV for a head (Frank Mosely). There’s a humor in seeing a scruffy, ’80s equivalent of a tech bro bring his white button-up and Spirit Halloween-coded sword to battle against humanoid cicada soldiers (Ixaroth’s lackeys) and Birney mines all the earned laughs from this mash-up between high fantasy and reality.

In many ways, “OBEX” works best when it embraces its roots as a fairy tale of sorts, even as it feels rooted in its contemporary tenderness about the human condition. This framework helps recontextualize earlier dialogue scenes in which characters can state the film’s central provocation out loud (“Someday we’ll all live in computers because life outside is too sad,” Conor says at one point), because characters in fairy tales often speak so overtly.

To some extent, it’s impossible to fully unplug from the ways technology and virtual worlds are enmeshed with our lives. Everything from the algorithms designed to keep us hooked on certain platforms to the addictive nature of blue light makes it far easier to ignore the world around us. Pointedly, Birney never lambasts Conor or others for whom this retreat is a reflex. But his film, like all the best art, is an invocation: not merely reflecting a despondent reality and world we know, but reminding us that there’s more to life than just the screen.