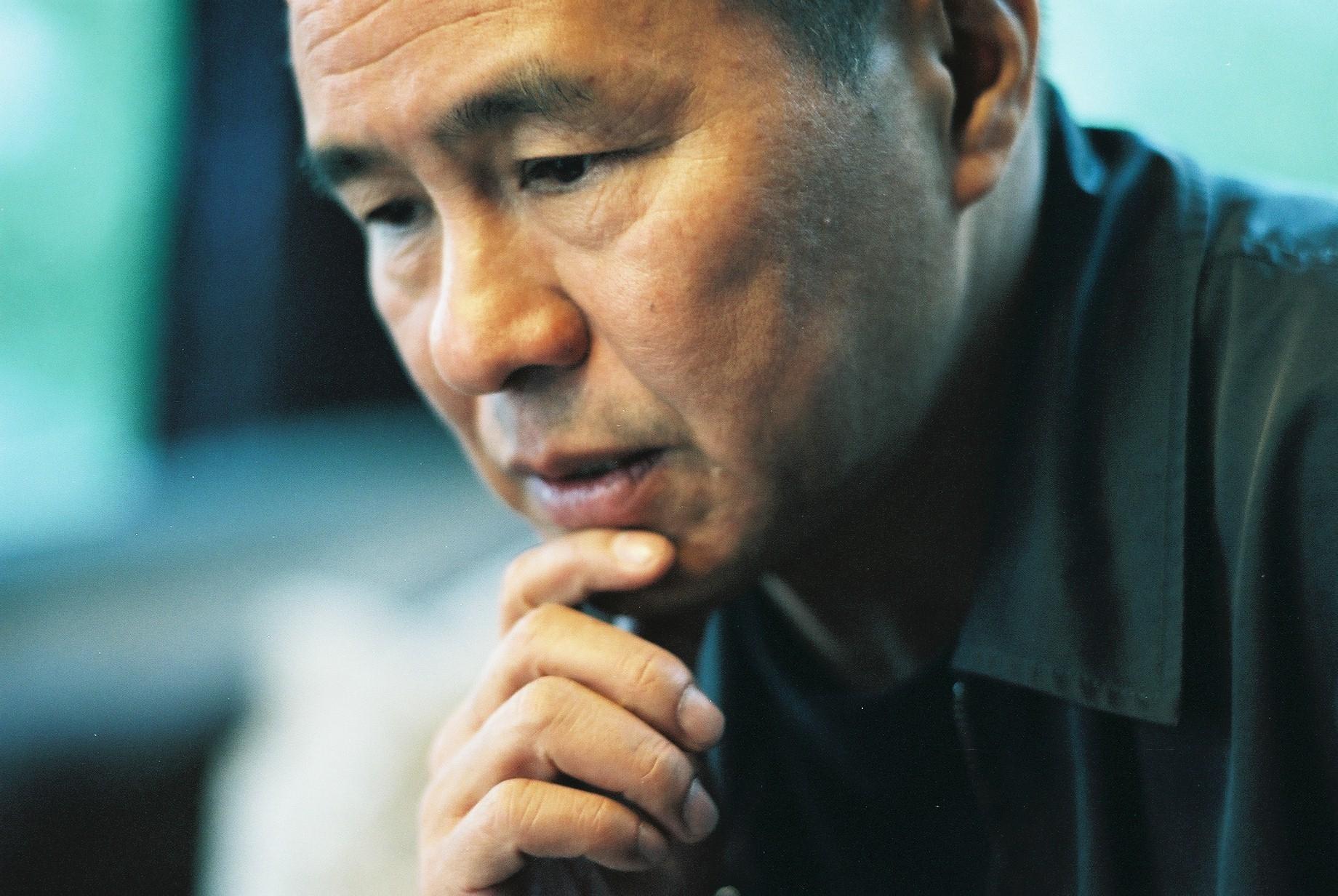

Hou Hsiao-hsien Movie Reviews

Blog Posts That Mention Hou Hsiao-hsien

Justifiable Revenge: Hou Hsiao-hsien on “The Assassin”

Glenn Heath, Jr.

It Ain’t the Meat (It’s the Motion): Thoughtson movie technique and movie criticism

Jim Emerson

Opening Shots: ‘Flowers of Shanghai’

Jim Emerson

Moviegoers who feel too much

Jim Emerson

The Golden Age of Cinemania is Now

Jim Emerson

Cannes 2024: Grand Tour, Motel Destino, Beating Hearts

Ben Kenigsberg

The Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Cinematic Universe

Hannah Benson

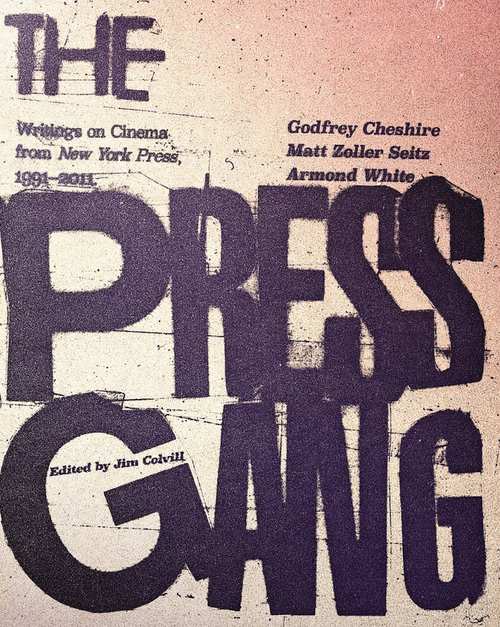

Gang of Three: A Conversation with Godfrey Cheshire, Matt Zoller Seitz, and Armond White

Craig D. Lindsey

NYFF 2020: Malmkrog, Days, I Carry You With Me

Godfrey Cheshire

Criterion’s “World Cinema Project, Vol. 2” Offers a Film Class in a Box

Brian Tallerico

Home Entertainment Consumer Guide: April 7, 2016

Brian Tallerico

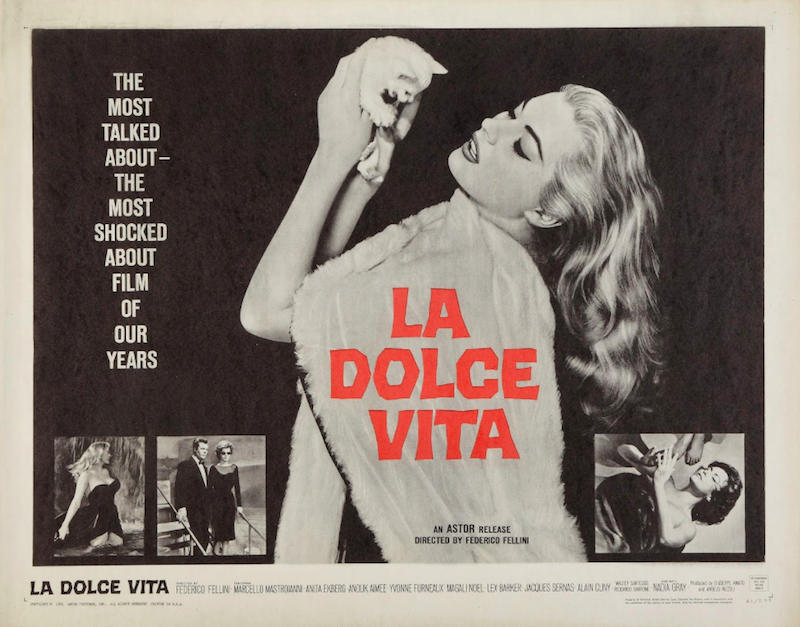

“La Dolce Vita” No More: On The Current State of Foreign-Language Film Distribution

Steve Erickson

A Living Cinematic Organism: Stephen Cone on “Henry Gamble’s Birthday Party”

Sheila O'Malley

The Best Performances of 2015

The Editors

NYFF: “Carol,” “The Assassin,” “Right Now, Wrong Then”

Scout Tafoya

CIFF 2015: Preview of the 51st Chicago International Film Festival

Nick Allen

Cannes 2015: Jacques Audiard’s “Dheepan” wins Palme d’Or

Ben Kenigsberg

Cannes 2015: Palme predictions

Ben Kenigsberg

Cannes 2015: “Youth,” “Madonna,” “The Assassin”

Barbara Scharres

Cannes 2015: “The Lobster,” “Irrational Man”

Barbara Scharres

Alterna-Cannes 2015

Ben Kenigsberg

Welcome to Cannes 2015

Barbara Scharres

Thumbnails 9/18/14

Matt Fagerholm

Ebert’s Four-Star Movies of 2006

Roger Ebert

Ebert & Scorsese: Best Films of the 1990s

Roger Ebert

“The Tree of Life” takes the Palme d’Or

Roger Ebert

WALL-E scrunches Love Guru inVillage Voice/LA Weekly crix poll

Jim Emerson

Sensitivity training: the fallacy of feelings

Jim Emerson

Into the Great Big Boring

Jim Emerson

So many films, so little time

Roger Ebert

Cannes coda: Why it’s all worth it

Roger Ebert

Telluride #4: A cleansing rain of films

Roger Ebert

Giants return to Cannes

Roger Ebert

Star Power and Small Gems Get Equal Time at Festival

Roger Ebert

Cannes all winners

Roger Ebert

Fighting over Bergman’s legacy

Roger Ebert

Popular Reviews

The best movie reviews, in your inbox