For nearly a decade Hou Hsiao-hsien has been in-production on The Assassin, a wuxia film about the triangular relationship between identity, war, and resistance set in ninth-century China. Production delays, a ballooning budget, and limited media access gave the project a mysterious reputation even before a single frame was revealed. With great anticipation, “The Assassin” finally premiered at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival in May to near-universal praise.

Known for roving long takes, distanced set-ups and elliptical pacing, Hou’s cinema subverts conventions of time and space. Realism is paramount; textures, design, and light collide with bodies walking through the frame over long durations.”The Assassin” feels like the next step in the evolution of this aesthetic, cherishing observation but also igniting a curiosity in narrative abstraction.

The film tells a classic story of revenge in the most complex of ways, limiting information about plot and circumstance in favor of physical momentum and emotional trauma. There’s impressive fight and flight, but it’s the unspoken sparring of faces that takes center stage.

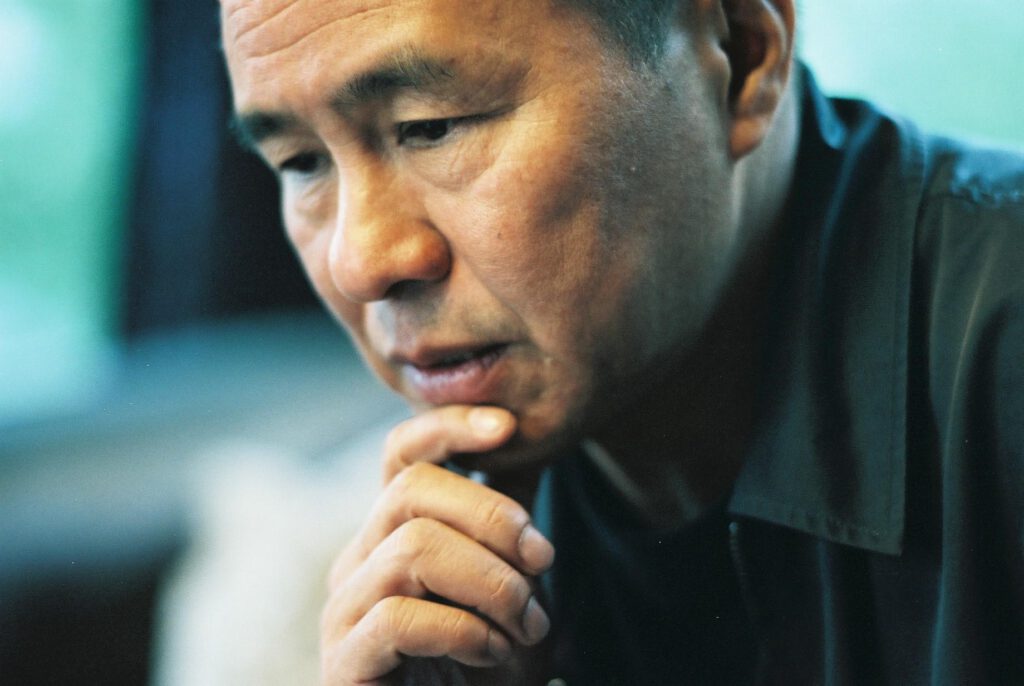

Hou spoke about his passion for wuxia, its resonant themes and his stylistic approach during an interview after “The Assassin” premiered on the Croisette for critics and industry professionals.

When did you first

experience the wuxia film?

I didn’t experience true

wuxia films until high school and college. I remember seeing the films of King

Hu and the Shaw Brothers. Even before that, though, I was struck by the power

of the wuxia novels. They left the biggest impact on me. I was reading these

books as early as elementary school, and like many of the films I viewed later

in life, it was the characters the moved me more than anything else.

In critiquing

reactionary tendencies of those in power, The

Assassin strikes me as a staunch anti-war film. Do you agree?

Yes, I agree to a point.

There are elements in the film that would suggest it’s a critique of war. But

that’s not why I necessarily made the film. I made the film to tell a

story about complex characters dealing with the idea of revenge, the idea that

revenge may be justified, not on behalf of a nation or personal interest, but

to avenge your family.

During many of the

film scenes, your camera stays at a distance, letting the action unfold from

afar without cutting in. Why did you choose this approach?

I can’t help

it. This is what I’m used to. This is how I have been making films

for so long. Whether it’s drama or action, I choose to let the scene unfold in

a realistic way. Plus, the closer the camera gets the more pressure it puts on

actors. I like to give the actors the space to feel comfortable.

Please discuss the use

of color in the film.

The film’s art director

was in charge of travelling to India and Korea in search for the silks of the

past. I wanted texture and striking color. These silks have a critical

relationship to light, especially in some of the interior scenes. We

created a visual tone through color. We understood what red, and gold, and

green could lend to a given image. The different settings developed from there.

What was it like

filming in such a variety of locations?

There’s grandeur to them

that we wanted to convey. We filmed a lot of the interiors in The Hubei Province,

but also a lot of the sequences with mountains and lakes. We looked at

each location with an attention to detail. You see it in the cracks in walls,

the bamboo in the columns and posts. This is the reality of life there

and it’s what I took from my experiences shooting the film.

The violence in “The Assassin” is very swift, quiet,

sudden and bloodless. Why choose this more muted approach?

I wanted to make a film

without blood. I am tired of seeing blood flowing on screen. It’s

excessive and has stopped having meaning for me. There are so many places you

can find such imagery, but I refuse to go down this road.

What is your fondest

memory of the production?

Every moment of filming

brought surprises. I was discovering so many new places in China. There was a

forest of white birches, the lakes with mist swirling up. Only when you’re

there do you get a sense of the scale of China. I was born there, but I

had never been to such places. I’d been to China before, but not places like

this, with their size and beauty. These places had a profound impact on me.