On a quiet morning in Yorkshire, England, a policeman chuckles over a voicemail he receives from his son, asking if he can skip school for the day. “I’m the soft touch,” the smiling copper explains to his colleague in their squad car. A minute later, the pair, along with a heavily armed S.W.A.T. team, break down the door of the Miller family home, arrest their 13-year-old son Jamie for the murder of a classmate, and change the lives of all concerned forever.

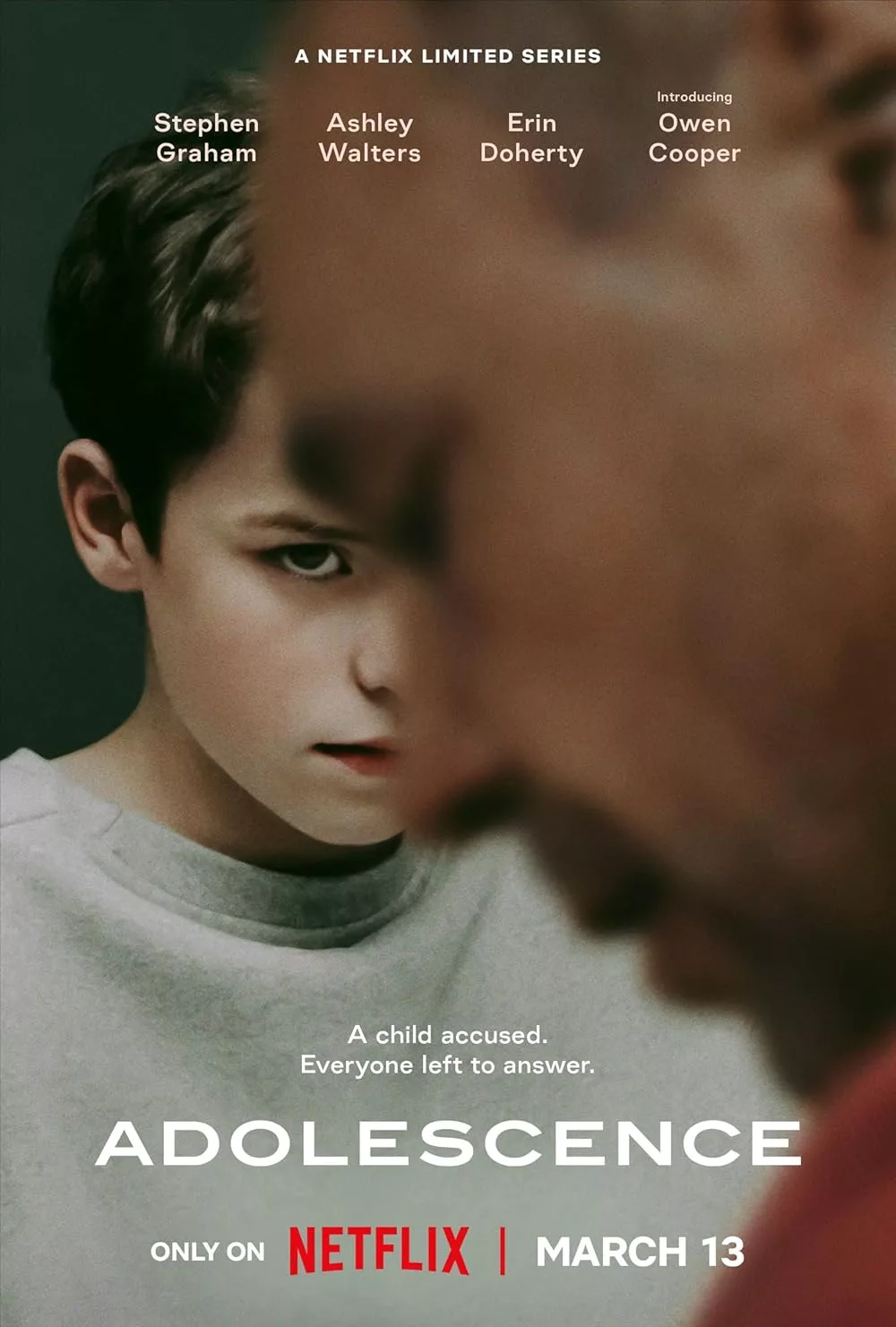

So begins the agonizing new limited series “Adolescence.” Written and created by Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham (the latter also provides a blistering performance as Jamie’s dad Eddie) and deftly directed by Philip Barantini, each episode is shot in a single take. Unlike “Birdman” or “1917,” the camera rarely swoops to white or black to steal an edit. This is a second-by-second examination of human psychology, the anguish of parenthood, and the failures of all the systems that, ostensibly, should help and protect teenagers. Every episode unfolds like a play (every event happens in real time), but this pulls the narrative string so taut that, at times, the story is unbearable. This is not a criticism. Like “Broadchurch,” “Adolescence” was written in a manner so the audience cannot look away, nor should it.

Episode one follows the Miller family—dad Eddie (Graham), mom Manda (Christine Tremarco) and older sister Lisa (Amelie Pease) as they sit, shell-shocked, in the police station’s family room, while Jamie (newcomer Owen Cooper) is held in a cell. A solicitor is summoned, blood samples are taken, a strip-search (not shown on camera) is performed. You can practically hear Eddie’s silenced tears—this is a career-best performance for Graham—and his suppressed indignation; you can feel the stomach-churning knots riling up Manda and Lisa’s insides. Meanwhile, Detective Inspector Bascombe (Ashley Walters) and Detective Sergeant Misha Frank (Faye Marsay) go through the motions of processing a suspect, almost, but not fully inured to the cruelty and detachment of both the crime and the manner of its investigation.

Were this an American series, the crime would’ve entailed a shooting, not a stabbing. The suspect would’ve been tossed, handcuffed, into a squad car while everyone screamed. The interrogation would engage in “Law & Order”-style tactics of obfuscation, yelling, and moral posturing. Just last week, I praised “Toxic Town,” also written by Thorne, for its emotional economy, and the same holds true for “Adolescence.” Here, every episode features a different setting and timeframe, allowing for layer upon layer of context to build within the story. Not a second of it feels excessive, though it does feel like an intrusion into the worst moments of the lives of each character. And yes, the narrative, aside from a few dialogues by DS Frank during the investigation, doesn’t spend too much time on the victim, nor do we meet her family. But there’s no end to films/TV about what happens to the loved ones of the deceased. If rehabilitative justice is the goal—if you believe in forgiveness, or at least transformative change for youthful offenders—there is no reason to not tell this story from a vantage point that includes the shame and horror of the suspect’s family, the struggles of the teenagers’ hapless educators, and the intractable anger and fear of the teenagers impacted by the violence.

“Adolescence” benefits from not being Graham and Barantini’s first one-take venture. The excellent 2021 film “Boiling Point,” based on the pair’s short film of the same name, was also shot in a single take. (It bears some resemblance to the “Review” episode of first season of “The Bear,” in terms of subject matter and emotional intensity.) Graham, therefore, is the perfect ballast for the ensemble. He is a father doing his damnedest to grasp what his son is accused of, what that means for his family, and, most painfully of all, what that says about him as a parent. This is a performance so acute, so wrenching, that I repeatedly broke down. Tremarco, too, is a revelation as a mother fighting back screaming sobs, bookending Graham’s more physical performance with grace, and Ashley Walters conducts a masterclass in body language, holding tall and firm on the job, but wilting as his own inability to understand the lives of teenagers, including and especially his son, rises to the fore.

Though the entire cast deserves credit for their extraordinary performances, no one holds a candle to Cooper. As Jamie Miller, he captures with perfection the quicksilver nature of those fraught years between childhood and adulthood. Nowhere is his skill more significantly displayed than in episode three, in which Jamie goes toe-to-toe with Briony (Erin Doherty, near-flawless), a psychologist visiting him in jail to write a pre-sentencing report. From minute to minute, Cooper powers through the tidal waves of emotion we associate with teenagers: he is friendly, he is self-deprecating, he is charming, he is irate, he is funny, he is cruel, he is lost. Actors playing teenagers in film/television are often in their 20s and simply look younger. Cooper is 15; according to an interview with him and Barantini, this seems to have made it easier for Cooper to tackle the challenges of “Adolescence” and enjoy swing ball between takes, while the adults at the monitors wept. To watch this young man is to have your heart torn asunder. It is almost impossible to believe that this is his first acting credit, and there is no doubt he has a long career ahead of him.

In Lydia Millet’s short story collection Fight No More, a retired professor, upon realizing her new caregiver, a former cam girl, has escaped a sexually abusive stepfather, thinks to herself, “The children. What we do to our children.” “Adolescence” shares this circumspection. No one will want to watch this series, but that is precisely why everyone should. If you’re a counselor, parent, and/or a teacher, it will likely take you to a very dark place; as a former teacher, it resurrected more than a few somber memories of my few years in the profession. However, “Adolescence” is not without hope, not without compassion. And if we care enough to understand them, neither are teenagers.

Entire series screened for review.