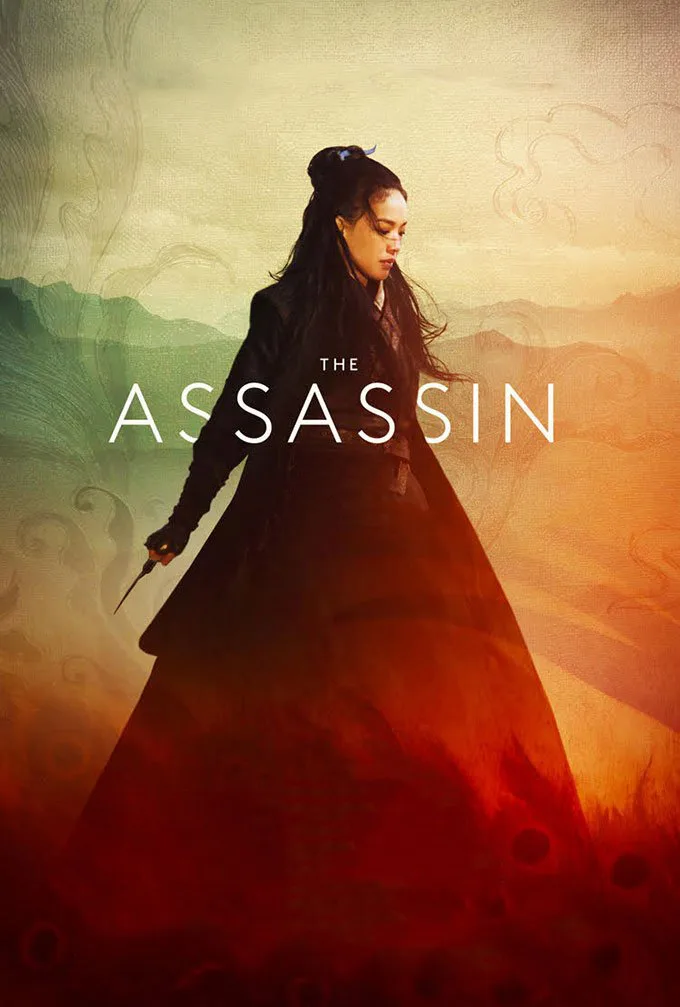

After a brief detour to pick up the Best Director award at Cannes earlier this year, “The Assassin,” the eagerly awaited historical martial arts epic from renowned Chinese filmmaker Hou Hsiao-Hsien, has finally arrived on our shores and it is indeed a curious experience. The story is told in such an enigmatic manner that even with the voluminous notes that I took during the screening, I remain somewhat confused by certain plot points. On the other hand, conventional and easy-to-follow narratives can be found anywhere, but very few of them occur in films that are as visually ravishing and formally graceful as what Hou has cooked up here.

Set in ninth-century China during a time of unrest that would eventually lead to the decline of the Tand Dynasty, “The Assassin” tells the story of Nie Yinniang (Shu Qui), who was kidnapped by her family when she was only 10 by Jiaxin (Sheu Fang-yi), a nun who trained her to become a brutally efficient assassin specializing in killing corrupt government officials. As the story begins, she demonstrates her abilities by killing her target—a man on horseback—with such lethal precision that it takes both her victim and viewers of the film a few moments to register that the deed has been done. Alas, Yinniang is not quite as ruthless as she seems to be, and when she confronts her next target and finds his young son in the room with him, she finds that she is unable to do the deed and lets him live.

This act of mercy sends Jiaxin into a rage, and she devises a plan that she believes will force Yinniang to do her duty and divest her of the sympathy that caused her to fail her previous mission. Yinniang is sent to Weibo, the largest province and one where the Imperial Court is currently of an unstable nature, to kill the governor, Lord Tian Ji’an (Chang Chen), and plunge the region into chaos. This is a bit tricky for Yinniang because not only is Lord Tian her cousin, it is revealed that before her disappearance, she was supposed to one day marry him in a union that would have helped bring lasting peace between the region and his court. Of course, Yinniang cannot bring herself to kill Lord Tian, though she does perform a series of brief ambushes designed to alert him to her presence. At the same time, Lord Tian dismisses his right-hand man, Xia Jing (Juan Ching-tian) from the court because of his outspoken nature and it is Xia’s reaction to this that turns out to be the spark that incites the battles to come.

Instead of rushing through the plot-oriented material in order to get to the action, Hou allows the story to reveal itself in a deliberately slow and occasionally digressive manner that prefers having characters recount their stories directly, rather than streamlining the plot threads with flashbacks and other tricks. For those not used to this manner of storytelling, especially in the context of what is supposed to be a martial arts narrative, “The Assassin” may prove to be bewildering. That said, it should be stressed that the story is confusing but not confused, and my guess is that it will make a lot more sense upon a second viewing.

And for many of those who see “The Assassin,” a second viewing will probably be in the cards as other aspects of the film are simple stunning to behold. Shooting in glorious 35mm, Hou and cinematographer Mark Lee Ping Bing have come up with the most stylistically fascinating and visually striking work of their numerous collaborations—there is not a single uninteresting shot that I can recall and many are so beautiful that one looks at them as they might observe a painting in a museum. The fight scenes have been devised in a way so that they are drained of all lurid excess in order to accentuate that participating in such violence is merely a job for Yinniang, and not something that she derives any pleasure from—that said, the combat staging is still so expertly done despite the lack of tricked-up editing or flashy camera moves that it stands as a silent rebuke to all the noisy and messy dust-ups in most contemporary blockbusters. Besides, a film does not need such visual fripperies when it has a presence as magnetic as Shu Qui at its center. In her third collaboration with Hou, she is never less than absolutely mesmerizing, adding immeasurably to the dramatic heft of the story.

Moviegoers attending “The Assassin” in the hopes of seeing another auteur-driven martial arts epic along the lines of “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,” “House of Flying Shadows” or “The Grandmaster” are likely to come away from it feeling a little disappointed—those who dig the genre because of the bloodshed will be appalled to discover that it is practically gore-free. However, if they are at the film because they want to be transported to another time and place by a world-class filmmaker working at the peak of his powers, they’re likely to find themselves as enraptured as I was by what Hou has come up with this time around.