In Korean, there’s a custom called 삼년상 (phonetic spelling/pronunciation: sam-nyun-sang). Back in the days of the Joseon dynasty, when a household’s father passed away, it was customary for adult children, even after the funeral, to build a shack near the burial site and live there for at least three years. It represents a way for a child to repay their parents for the first three years, when they were helpless without their parents’ help. One could certainly still grieve after three years if they wished, but there was a minimum expectancy of how long someone should mourn.

I find it fascinating that in Korean culture, there’s a built-in “bare minimum” for sadness; there’s a linearity to anguish and grief that’s embedded in the language itself. I thought about this concept while watching director Park Chan-wook’s latest, “No Other Choice,” an acerbic and farcical black comedy made for this era of mass layoffs, quiet quitting, and a crumbling job market.

Lee Byung-hun, in a welcome change from the action-hero roles he’s best known for to Western audiences, plays the well-meaning and loyal Man-su, a longtime employee of the paper company Solar Paper. When he is unceremoniously fired from his job (“You Americans say that to be fired is to be ‘axed?’ [In Korea we say] off with your head!” he says, highlighting cultural differences in how one’s vocation is intimately tied to one’s self-worth), his sense of identity crumbles. When he sees the burden of being unable to financially provide for his wife, Lee Mi-ri (Son Ye-jin), and his children, Si-one (Woo Seung Kim) and Ri-one (So Yul Choi), he hatches a brutal plan to regain his pride: eliminate the other job applicants for the position that he’s gunning for.

Of course, the irony of the film’s title is that Man-su has many other choices than murder. Rather than turn his frustrations towards the systems preying upon people like him, he harms those he could instead be in community with, and his stubbornness to work in one specific area corrupts his imagination, preventing him from considering other ways of provision.

“The great tragedy of this film is that his rage is not aimed at the right target; he points his gun at people who are his double, those just like him, those he should empathize with the most, instead of the company that fired him in one stroke, even after he toiled there for 25 years,” Director Park shared.

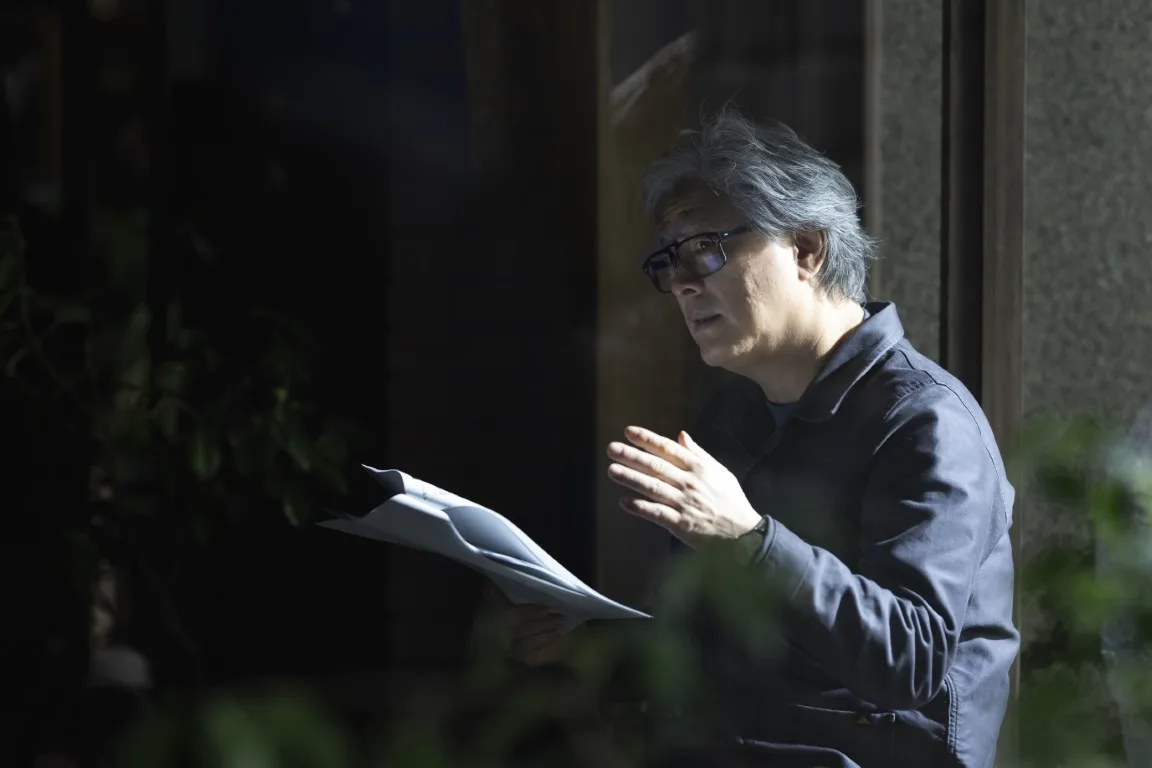

Over Zoom, Park and Lee, whose words were graciously translated by Ji-won Lee and Isue Shin, spoke to RogerEbert.com separately; this piece combines their interviews into one, fluid conversation. They unpacked the fatal foolishness of Man-su’s crusade, how the film’s interplay of light helps us understand the characters’ interiority in a given scene, and how working on the project has reshaped their relationship to disappointment and failure.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Director Park, there’s a palpable anger that courses through your projects, from your aptly titled Vengeance trilogy to the romantic disquietude of “Decision to Leave.” I’m curious if you view filmmaking as a vessel for holding the rage you feel about the world, and how that’s evolved for you as a filmmaker?

PC: Certainly, the movies I’ve made in the past–as you mentioned–portrayed that feeling of rage in great detail, but for this film, I wanted to take the opposite approach from my past work. Man-su’s rage is captured in a single line in the film, where he says [paraphrased] “You bossed me around for 25 years.” He may have his frustrations towards the company or the capitalist system, but because he is thinking realistically about his life, he accepts his inability to change them in some respects. He accepts the reality that he’s living in and instead tries to be pragmatic about his goals and benefits, which leads him to think that if he wants to get his job back, he has to kill other people.

What’s sad is that the targets that he tries to eliminate are not the targets of his rage or the progenitors of his pain. These are people in a situation similar to his. He should be able to understand them and be friends with them. The great tragedy of this film is that his rage is not aimed at the right target; he points his gun at people who are his double, those just like him, those he should empathize with the most, instead of the company that fired him in one stroke, even after he toiled there for 25 years. That’s where foolishness comes in as well: he sees the people who are just like him as his targets. He can’t think of any other methods and has failed to find an alternative to regain the confidence and respect he has as a father and husband.

All of the applicants should have instead teamed up to take down the system. Your response reminds me of a scene where Man-su’s first target, Goo Beom-mo (Lee Sung-min), is so frustrated that he rolls around outside, screaming silently. The expression of our agony always has to be palatable, but really, sometimes all we want to do is scream unceremoniously.

PC: Even in that scene, Beom-mo wants to cry out loud, but is worried his wife might hear him, so he has to hold it in as much as possible. He has to ration out his moans; I think that makes him more sympathetic. You feel bad for him because he looks so pathetic. After all, he has to do that.

Lee Byung-hun, across projects like “The Good, the Bad, the Weird,”” Emergency Declaration,” “Concrete Utopia,”… you’ve had the opportunity to play a very particular brand of Korean masculinity. Your role as Man-su in “No Other Choice” complicates that. Can you speak to how your approach to playing patriarchal figures has evolved throughout your career or how you view these roles in conversation?

LB: Man-su is just an ordinary man. His main goal is to protect his family, and that’s something I relate to; I might not have the same life as him, but initially, the entry point to empathy wasn’t difficult. What was difficult was the extremity of these situations Man-su finds himself in; my mind is not like his, so in trying to get a hold of who he is, I had to first understand that these are not “ordinary decisions.” Comprehending that, understanding that someone who isn’t similar to me can then be pushed in such a way to make these severe choices, to own that was the truly difficult part.

As opposed to Man-su’s particular brand of masculinity, because I was born and grew up in Korea, I do understand his embodiment of patriarchy. I think that, because of this era of globalization and the more consistent exchange of cultures, we move together more easily regarding cultural changes. A lot of the macho spirit and male chauvinism that defines Korean men, I think, has largely disappeared. There are still traces of it, though; it’s not always overt, and so playing a character who is “modernly masculine,” for whom those footprints of toxicity remain, was an interesting challenge.

Yeong-tak, your character from “Concrete Utopia,” has shades of Man-su, since both view their sense of provision as deeply tied to homeownership.

LB: I think both are very Korean stories in that respect. In “Concrete Utopia,” even in the aftermath of devastation, people’s sense of security is so deeply tied to home ownership, and the protection of family comes from nurturing within that home. It’s interesting to tackle these ideas, but with different filmmakers.

Director Park, I’m struck by the spectre of Man-su’s father; he occupies the film as a sort of phantasm, who leaves behind not just a gun, but particular narratives around what it means to be a provider and a man to his son. Through the process of adapting Donald Westlake’s novel, did it offer you an opportunity to reflect on the familiar narratives you were raised with (and which ones you wanted to either accept or reject)

PC: (Laughs) I wasn’t quite the rebel to my parents, but I also wasn’t someone who obeyed everything they said or told me to do.

I like the insight about how Man-su’s father is like a ghost in the film, that he’s lingering and flickering in the background; he’s a part of the movie, but he’s unseen. There was never a plan to depict Man-su’s father in the film, but if it weren’t for Man-su’s father’s gun, which Man-su saw repeatedly day in and day out, Man-su might not have ever planned these murders in the first place. Murdering your competition is a foolish idea in the first place, but the presence of a firearm enabled Man-su to act.

I think Man-su was trying to be different from his father. Whereas his father raised and killed pigs, I think that motivated Man-su to become a lover of plants. On top of that, Man-su dismantled the garage his father had used to hang himself in and instead built a greenhouse. He wanted to live his life differently from the way his father did.

Yet in the scene where his son, Si-one, is taken by the place, Man-su quotes his own father’s words to his son. He’s basically telling his son to make a false statement to the police, and in doing so, is passing down trauma and history that he didn’t want to inherit from his father in the first place. What Man-su didn’t want to inherit from his dad, he inherited anyway, and he also passed the same vice down to his own son.

I’ll keep an eye out for “No Other Choice 2” that follows Si-one’s violent escapades. Lee Byung-hun, I was struck by a line A-ra says to Beom-mo: “It’s not the fact that you lost your job; it’s how you handled it.” Disappointment and rejection seem par for the course when working in the film industry; has working on the project offered you a chance to reflect on how you process moments of loss?

LB: (Laughs) Are you saying that now if I experience hardship, I should just get rid of my competitors?

I mean, I’m not not saying that …

LB: I think actors learn a lot through the characters that they play, and it also causes them to sometimes change their own opinions. With any character I’ve embodied, my ego and my complete selfhood have been affected to a certain extent, and my worldview is constantly challenged. I think that, for many actors and even directors and creatives who make art, when one project ends, the next job prospect is very tentative, so many are always in a pseudo-state of joblessness. I think I’ve been really lucky to be in a position to choose my next project, but I know many creatives are always in a limbo-like state.

To that point, though, even within your career, a role like “No Other Choice” is special because you get to flex more of your comedic muscles.

LBH: I actually love the genre of black comedy quite a lot. Even “Concrete Utopia,” I would say, belongs to this genre. The story is very dark and depressing, as it is a disaster project, but there are many ironic and humorous situations. A lot of people have seen me in action films and also very serious dramas, and so, especially to a Western audience, it might be new to see me in a more comedic role.

Director Park, what you articulated about inherited trauma between Si-one and Man-su reminds me of another line spoken by Lee Mi-ri: “If you do anything bad, it means we’re in it together.” There’s a loyalty to the family you explore that’s both toxic and protective; I feel like deconstructing the safety of the family unit is a provocation that’s been a theme in your work.

Yes, that is great insight because Mi-ri is someone who doesn’t blame other people, and even if she has done nothing wrong herself, she still takes responsibility. Even though she had no part in the murders her husband committed, she’s someone who’s asking, “Did I play a part?” I really did want to show this character’s maturity.

Yet if you look into it, the irony is that, perhaps unknowingly, she had a more direct role in what happens than you’d think. She was the one who inspired the first murder because she said something akin to “I hope that person gets hit by lightning.” There’s also a time when she reminded Man-su that he was an alcoholic and almost choked to death on his own puke, and that inspired the method for the second murder.

Even though she wasn’t intentionally doing so, she inspired the murder twice. Through this, I wanted to show how closely interrelated this couple is and that one person’s wrongdoing is not just the individual’s. Even if an individual commits an act, it’s not solely that person’s responsibility. Everyone is implicated.

Lee Byung-hun, I’m struck by Director Park’s use of light in the film. There are, of course, the blue light of phone screens, but I also think of the natural light; how it bathes the family in the opening scenes, how it blinds Man-su in one of his interviews.

LB: Lighting is definitely such a huge component of this project and something that has deep meaning with the story that Man-su goes through, because the light can be representative of the difficulties, the hardships, or even the discomforts that the character may experience. I wanted to note that for Director Park’s films, even the smallest prop or branch that’s far away holds meaning. There are people on the crew who are putting immense attention to detail into every element. So whether it’s color or lighting, these aspects were all thought of very meticulously.

The interview scene you mentioned is one I love a lot because it’s a moment when Man-su is being harassed by all these elements of his environment. The lighting further reinforces the sense that the world is out to get him, and it feeds into the frustration and desperation that later curdle into something worse.

I also want to mention the moment where Man-su is burying his last victim, and his wife is holding the flashlight. The screen splits in two; it’s a moment of genius on Director Park’s end to showcase the different light sources guiding the characters, the artificial sources they use to illuminate their various misdeeds, while they’re under the natural light of the moon.

“No Other Choice” is now in theaters via NEON.