The hardest part to stomach about “28 Years: The Bone Temple” is its meaninglessness. The second part of a planned trilogy, or I guess the fourth film of a quintet, usually comes with the whiff of being a transitory act, where the question of how this part relates to the whole overwhelms the integrity of the part.

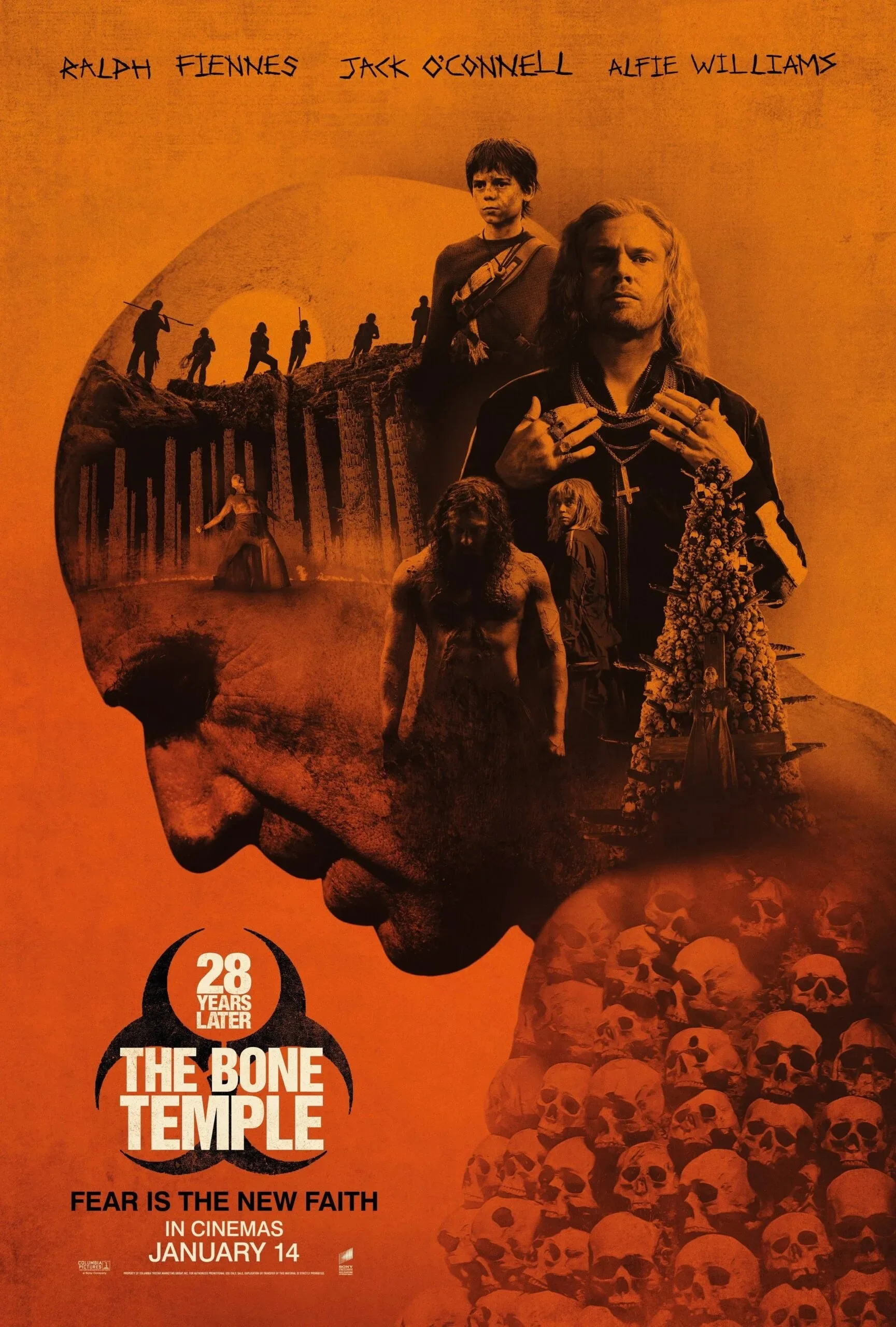

The previous Danny Boyle-directed film, “28 Years Later,” was a startling total shift. It pushed viewers from the post-apocalyptic angst of the previous trilogy into a grim childlike fairytale, as seen through the impressionable eyes of Spike (Alfie Williams), that wound viewers past a killer Apex named Samson (Chi Lewis-Parry) and a slender memorial composed of bones built by the aloof Dr. Ian Kelson (Ralph Fiennes). That film concluded with Spike in the grasp of a murderous Jimmy Savile-inspired cult led by Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal (Jack O’Connell). On its face, however, Nia DaCosta’s turn in the franchise doesn’t promise anything radically different; unlike the previous titles in this franchise, which are differentiated by their passage of time, this one is temporally bound by the colon in its title. Rather the film, to borrow Ian’s “Spinal Tap” reference here, turns the bleakness, bloodiness, and brutality up to 11—making “28 Years Later: The Bone Temple” a gnarly, mind-bending trek through inhumanity.

If the end of “28 Years Later” promised a horrific future for Spike, then “The Bone Temple” delivers. Jimmy Crystal and his goons, known as the Fingers—each has a variation on the name Jimmy—are Satanists dressed in tracksuits and terrible blonde wigs who believe Jimmy Crystal is the son of a figure known as “Old Nick.” Jimmy Crystal, per his teachings, believes he needs seven strong fingers to hold his desolate domain—so he forces Spike to fight for his life against one of the Jimmys. The knife battle to the death takes place inside of a disused waterpark’s empty pool. A jagged, stuttering whip pan, which imitates the handheld action of “28 Days Later,” menacingly encircles Spike, whose desperate cries fills a space that once, now long ago, held children’s laughter. He wins, becoming one of the Jimmys. But his salvation is short lived.

In “The Bone Temple,” moments of kindness are akin to drips of water on an inferno. They sparsely occur in unlikely places, like Jimmy Ink (Erin Kellyman) allowing Spike not to partake in the skinning of a family or covering for him when he fumbles capturing the group’s human prey. Alex Garland’s heavy-handed script oscillates from Spike’s hellish journey to Ian’s eccentric routine. The doctor lives in a tiny bunker underneath his skeletal memorial, listening to Duran Duran on vinyl and recording his observations of Samson, who he discovers actually pines for the drug-induced sedation provided by Ian’s darts. For a time, in fact, the film becomes a stoner hangout flick between a doctor and his patient. Ian speaks to Samson, hoping to induce language from him, and even dances and naps in the warm grass with him under the calm blanket of a hallucinogenic bliss. When Jimmy Ink catches sight of Ian with Samson, however, she believes she’s found Old Nick, and beckons Jimmy Crystal to grant the gang a meeting with his dark lord.

Apart from that direct line, which carries Spike back to Ian’s presence, “The Bone Temple” lacks conventional plotting. It can also be frustratingly distant from its characters. The film, via brief flashbacks and the swirling sound of trains, cars, and children laughing, slightly opens a window into Samson’s prior life, only to quickly shut it. Similar allusions are also made to Ian’s pre-pandemic world, which, he admits, he can barely recall. Spike spends much of the 109-minute run time as a vessel for trauma as he observes sights no child should see. None of the characters feel like fleshed-out people, and the plot lacks any momentum toward an emotional catharsis.

It would be a mistake, however, to assume these are glitches. For people to retain their humanity, shouldn’t they possess hopes, beliefs, and dreams? After witnessing 28 years of death and destruction, the rampaging infected and glib survivors, these characters are mostly dead inside. What is there for Spike, who lost his mother, father and community, to look forward to? Jimmy Crystal, who similarly watched his family murdered, is a stunted adolescent who references the Teletubbies and Jimmy Saville and has transferred his desire to see his pastor father again into a Satanist mythology. Knowing the destruction that lays beyond the Scottish Highlands, the Jimmys have found faith in him too. Meanwhile, Ian, an atheist, has maintained a fealty to his medical ethics. As the film progresses, each character’s ember of belief is fiercely snuffed out.

While I’ve always found director Nia DaCosta’s best work to be in non-legacy films, like “Little Woods” and her recent Ibsen re-imagining “Hedda,” films that allow her a full creative range of motion—she pulls off the challenge of imbuing importance into an inherently meaningless film with aplomb. She does so through incredible spectacle, whose conscious hollowness is telling. In one gleeful scene, a trippy, fiery, coke-induced post-apocalyptic mosh pit that involves Ian cosplaying as a demonic entity while Iron Maiden’s “The Number of the Beast” blares from the frame, is an alluring deconstruction of religion’s theatrics. It’s also a reminder that, by virtue of his unhurried timing and dry wit, whose punchlines arrive with the assuredness of a sloth, Fiennes is among his generation’s best comedic actors. If he wasn’t here providing unconventional emotion in equal doses, I’m not wholly sure if “The Bone Temple” would hold together. With him, the film rises close to the level of its predecessors.

And while Garland’s themes might arrive with the subtly of neon in the fog, often through overt dialogue about the film’s religious themes, DaCosta works these pieces into a smooth nihilistic message that wonders aloud why any God, if they exist, would forsake this world into a hellscape. (Though one could argue it’s saying that we’re already living in an era where we’re perpetually forced to choose the lesser of two evils in the hopes of surviving to the next day).

Nevertheless, if there’s one misstep to “The Bone Temple,” it’s the ending, which features a cameo that alters the tenor of the picture’s emotional hostility. While Boyle and company certainly have a plan to turn this “cheery” ending on its head—there’s a reference to why it was beneficial for the Allies to be helpful to the Axis at the end of World War II—one does somewhat wish the film committed to leaving us cold rather offering the warm glimmer of a further sequel.

“The Bone Temple” is strong enough on its own, without the colon.