The documentary “Holding Liat,” about an Israeli family trying to locate a son and daughter-in-law kidnapped by Hamas, is another entry in an unfortunately ever-growing body of work about the enmity between Israel and the Palestinians of the occupied West Bank, and the blood that continues to be spilled in its name.

The situation has been ongoing since the Israeli-Palestine war of 1948-49, which erupted soon after Israel’s official founding. That war ended with Israel annexing the West Bank and Eastern Jerusalem. That was more land than was originally envisioned in the 1947 United Nations Partition plan for Palestine, which was published after the British—who had seized Palestine from the occupying Ottomans, an ally of Germany, during World War I—recommended splitting the area between Arabs and Jews. Ancient, amorphous tensions now had a concrete modern focus. After multiple wars, the situation there is the worst it has ever been.

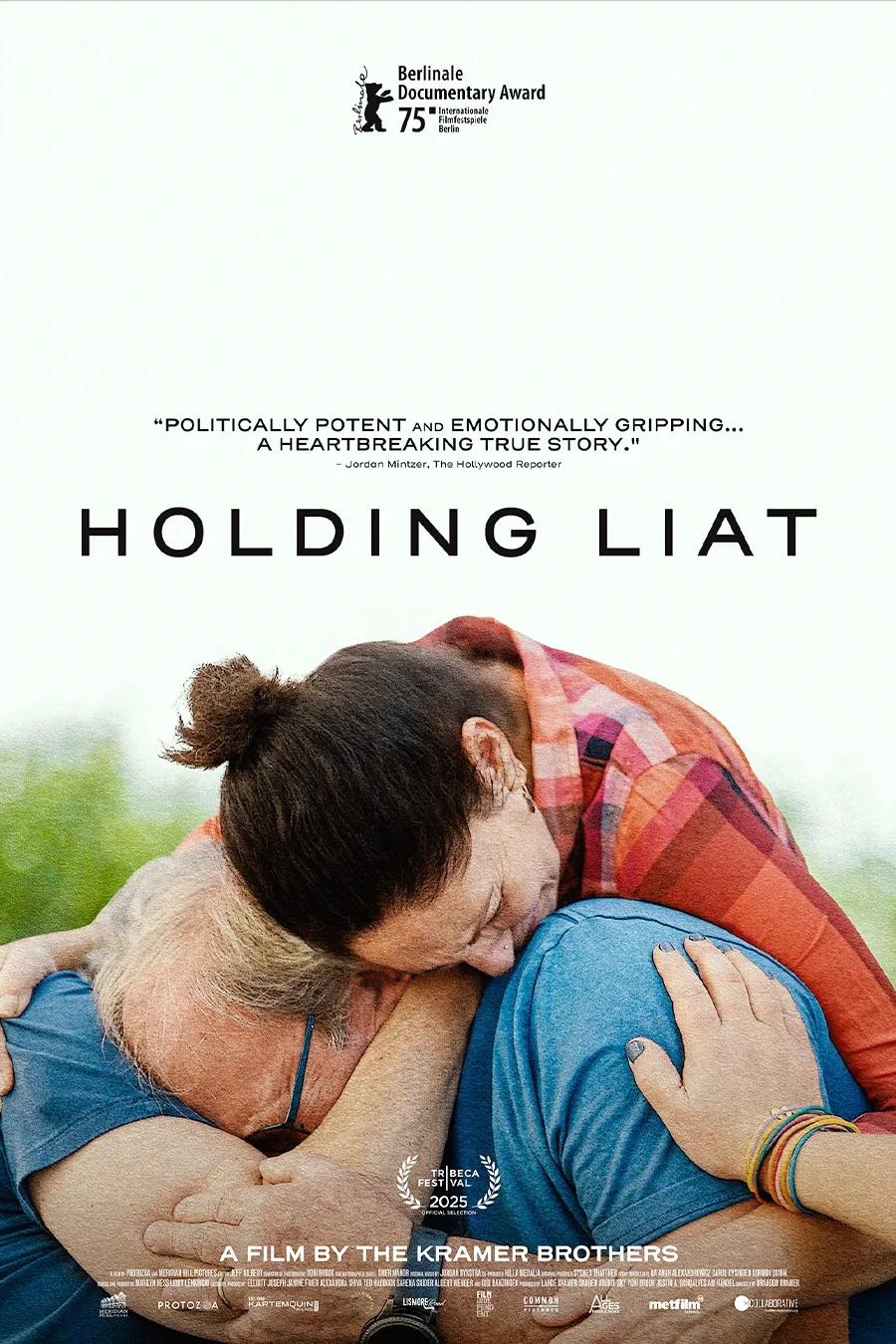

The Hamas-driven attacks of Oct. 7, 2023 sparked a drastic escalation, with the Israeli military spending the next two-plus years leveling Gaza and killing as many of its civilian inhabitants as possible. According to reports collated at Wikipedia, as of this month, the post-Oct. 7 body count stands at 73,600 Palestinians and 2,109 Israelis. The Israelis in”Holding Liat” are perfect subjects for a documentary about wartime trauma that hopes to reach beyond partisan enclaves. Its main subjects are the Atzilli and Beinin families, Israelis living on a kibbutz near the border. They had only recently been joined by the wedding of a son and daughter from each household: Aviv Atzilli, who managed the kibbutz’s agricultural garage, and his wife, Liat Beinin, a Holocaust history teacher.

Both families, but the Atzillis especially, had critical of the leadership of Israeli Prime Minster Benjamin “Bibi” Netanyahu long before the abductions and related atrocities of Oct. 7. They continue to be critical during the period covered in this movie, which is the days following the Hamas attacks. But most of the complaints pertain to the Netanyahu government’s inaction on behalf of kidnap victims and their loved ones, not the morality of the military retaliation, or the relationship between the Zionist mission and the occupation of mainly Palestinian areas (though the latter subjects do sometimes come up). “The hostages are not Bibi’s agenda,” says Liat’s father, Yehuda, aligning himself with those who believe the country’s Prime Minister viewed Oct. 7 not as a national tragedy but an opportunity.

The US-born Yehuda is a progressive who was once part of Hashomer Hatzair, a secular, socialist-inclined, pro-labor Zionist movement that built the kibbutz where both families live, and that advocated for a binational state in which Jews and Arabs would have equal rights under the law. How did Yehuda end up the protagonist of “Holding Liat”? Maybe it’s as simple as his comfort level at having cameras trained on him constantly, plus the fact that he is the most politically active person (publicly, anyway) in either family.

At the very least, Yehuda is the most inclined to frame the conflict as something other than a force majeure. At one point he goes to Washington, D.C. with his other daughter, Taj, as part of a group of families who lost loved ones in the kidnappings. He reacts with disgust at MAGA demonstrators and pro-militarist Israelis using the Oct. 7 as an “I told you so” pretext for full-on mechanized warfare targeting hospitals, schools, and other institutions that were supposed to be off-limits.

Yehuda also pushes back against Taj and the rest of the group’s marching orders: to play on the world’s heartstrings rather than dig into history, and avoid discussing US or Israeli policy decisions that, for generations, have kept the temperature in the Mideast somewhere between a low stovetop simmer and a boiler room explosion.The movie itself tends more towards the force majeure approach, though it can’t help but get specific when it focuses on Yehuda, whose muttered musings and answers to filmmakers’ questions show how bitterly, often amusingly, disgusted he is by the state of things.

The latter includes his own government’s outwardly polite but callous response to Israeli citizens struggling to get meaningful information about their missing loved ones from officials in what is, in theory anyway, a representative democracy. The movie begins with a phone conversation between Yehuda and a military official that has the tedious, bland quality of a call to a local utility company. When the family finally gets a response, it’s functionally useless because it’s not actionable for them. The bearer of the message is terse and disinterested, not even allowing themselves the luxury of a condolence.

“Generally speaking,” Yehuda says, “I like to be in control of events. Here, there are events over which we have no control, and we’re being led by crazy people, whether it’s on the Israeli [or] on the Palestinian side, and the result is all this death and destruction, and the whole situation makes me angry.”