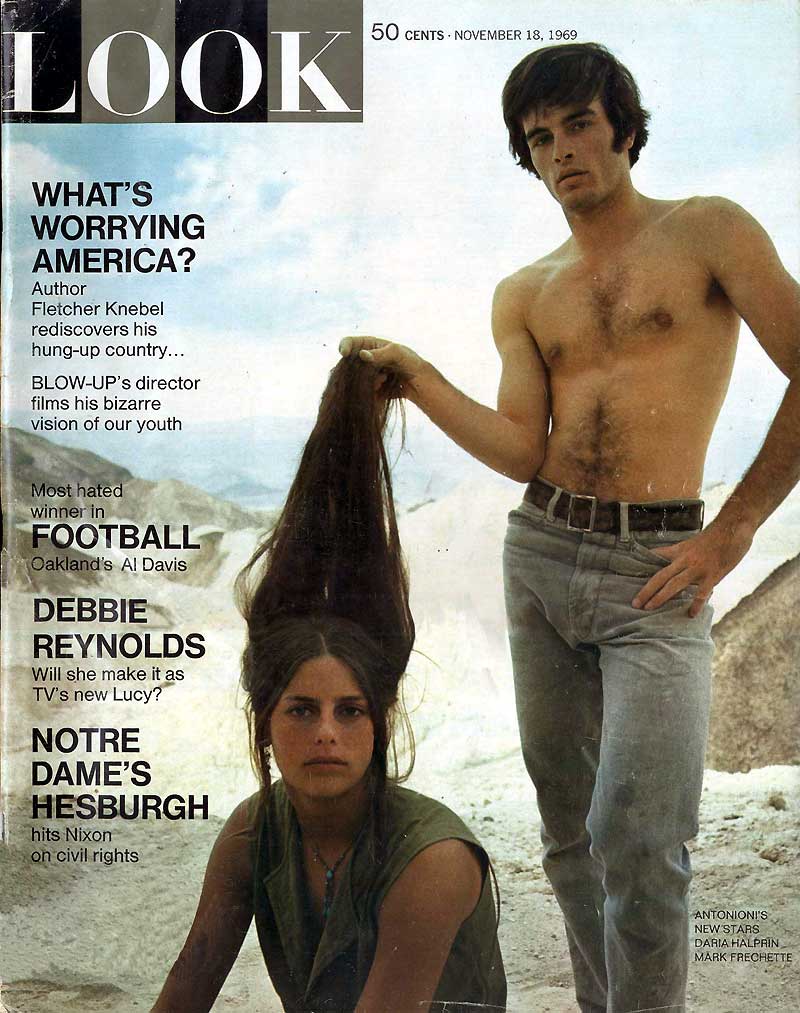

“Zabriskie Point” — an Antonioni movie on the cover of LOOK magazine in 1969: “Had he violated the Mann Act when he staged a nude love-in in a national park? Does the film show an “anti-American” bias? As a member of the movie Establishment, is he distorting the aims of the young people’s ‘revolution’?”

Watching Ingmar Bergman‘s “Shame” over the weekend (which I was pleased to find that I had not seen before — after 20 or 30 years, I sometimes forget), I recalled something that happened around 1982. Through the University of Washington Cinema Studies program, we brought the now-famous (then not-so-) story structure guru Robert McKee to campus to conduct a weekend screenwriting seminar. McKee, played by Brian Cox in Spike Jonze’s and Charlie Kaufman’s “Adapation.” as the ultimate authority on how to write a salable screenplay, has probably been the single-most dominant influence in American screenwriting — “Hollywood” and “independent” — over the last two decades. Many would say “pernicious influence.” (Syd Field is another.)

It’s not necessarily McKee’s fault that so many aspiring screenwriters and studio development executives have chosen to emphasize a cogent, three-act structure over all other aspects of the script, including things like character, ideas, and even coherent narrative. Structure, after all, is supposed to be merely the backbone of storytelling, not the be-all, end-all of screenwriting. But people focus on the things that are easiest to fix, that make something feel like a movie, moving from beat to beat, even if the finished product is just a waste of time.

The film McKee chose to illustrate the principles of a well-structured story that time was Ingmar Bergman’s “The Virgin Spring.”

“Shame” is another reminder that Bergman’s movies weren’t solely aimed at “art” — they were made to appeal to an audience. Right up to its bleak ending, “Shame” is a rip-roaring story, with plenty of action, plot-twists, big emotional scenes for actors to play, gorgeously meticulous cinematography, explosive special effects and flat-out absurdist comedy. I don’t know how “arty” it seemed in 1968, but it plays almost like classical mainstream moviemaking today. (And remember: Downbeat, nihilistic or inconclusive finales were very fashionable and popular in mainstream cinema in the late 1960’s: “Bonnie and Clyde,” “Blow-Up,” “Easy Rider,” “Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry”…),

It’s important to remember that Bergman and his fellow Euro-titan Michelangelo Antonioni, who both died on the same day last week, were big-name commercial directors — who also helped moviegoers worldwide see the relatively young, originally low-brow, populist medium in a new light: as a (potential) art form. (The Beatles, who in 1964-’65 were the most popular youth phenomenon on the planet, even wanted Antonioni to direct their second feature, after “A Hard Day's Night“!) And if they hadn’t been so popular and famous, they would not have been so influential. These guys won plenty of high-falutin’ awards at film festivals, but they were also nominated for Oscars in glitzy Hollywood.

Bergman was nominated nine times for writing and directing, and Antonioni twice, and their films, actors, and other collaborators received many more. (Fellini, their popular peer in the ’60s, received 12 Oscar nominations.) Liv Ullmann was nominated twice for best actress, in Bergman’s “Face to Face” and Jan Troell’s “The Emigrants“; Ingrid Bergman received her sixth Oscar nom for “Autumn Sonata”; cinematographer Sven Nykvist won two Oscars for “Cries and Whispers” and “Fanny and Alexander“; and Bergman’s Best Foreign Film winners include “The Virgin Spring,” “Through a Glass Darkly,” and “Fanny and Alexander.” “Cries and Whispers” was nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Picture of 1973 (not Foreign Language Film — Best Picture, something that wouldn’t happen again until 1995’s “Il Postino”), Director, Original Screenplay, Cinematography, and Costume Design.

All of which is to underline that Bergman and Antonioni were among the most prestigious, popular, and widely-discussed European filmmakers of their day. No, they weren’t Paul Verhoeven or Ang Lee (both of whom have made many more English-language films than Bergman or Antonioni), but they weren’t Bela Tarr or Theo Angelopoulos, either — the latters’ international reputations, awards, and honors notwithstanding. Bergman and Antonioni, like Fellini, were brand-names recognized by much of the moviegoing public, even among those who had never seen their movies.

(By the 1980s and ’90s, it didn’t even matter if the audience actually knew Bergman’s work when it was parodied on “SCTV” — “Whispers of the Wolf” on Count Floyd’s “Monster Chiller Horror Theater,” or Martin Short as Jerry Lewis in “Scenes From an Idiot’s Marriage” — or, even more broadly, in “Bill and Ted's Bogus Journey,” in which Death challenges the heroes to a game of Battleship. The style and visual archetypes, like Antonioni’s, were so distinctive they practically begged for parody. )

Even with the support of AB Svensk Filmindustri, Bergman had the same kinds of problems with financing, producers, and distributors, that most directors seem to have — as did Antonioni, Jean-Luc Godard and many of the well-known, critically hailed mid-century filmmakers. (Bergman and Antonioni are on record complaining about them — in the DVD extras for “Shame” and “L’Eclisse,” for instance.) And none of them ever met with unanimous critical approval. They’ve had prominent and influential detractors all along.

Jonathan Rosenbaum shouted a loud “No!” to Bergman in the New York Times Saturday, alleging that his work “isn’t being taught in film courses or debated by film buffs with the same intensity as Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard.” I don’t know what evidence supports this assertion, because Rosenbaum doesn’t say, but the rather passionate comments here, at least, don’t support Rosenbaum’s claim. Unless his aim was really just to stir up the pot, and thus disprove his own thesis, I think he’ll be surprised at how much mail that Op-Ed piece generates. It was a great publicity stunt, anyway.

Bergman and Antonioni have never been above criticism. But it’s foolish (and pointless) to dismiss either of them — now, more than ever.

As A.O. Scott wrote in the Times the next day (“Before Them, Films Were Just Movies“), though this was probably written before he read Rosenbaum’s piece, Bergman and Antonioni were important:

… Not only because they were both great filmmakers, but more because, in their prime, Mr. Antonioni and Mr. Bergman were seen as the twin embodiments of the idea that a filmmaker could be, without qualification or compromise, a great artist.

Not that everyone agreed or saw them both in equally glowing light. There will always be those who scoff at the idea of cinema as a form of art. And those who do embrace the notion have always been notoriously prone to quarrel and dissension.

Scott cites critic Philip Lopate, an ecstatic Antonioni partisan, whose crowd dismissed the more popular Bergman as “the darling of the suburbs.”

On the other hand, Manny Farber slammed Michelangelo: “Antonioni’s aspiration is to pin the viewer to the wall and slug him with wet towels of artiness and significance.”

Andrew Sarris made fun of “Antoniennui.” Pauline Kael hated “L’Eclisse” (“Some like it cold…. Even [Monica Vitti] looks like she’s given up in this one”), and complained:

Will “Blow-Up” be taken seriously in 1968 only by the same sort of cultural diehards who are still sending out five-page single-spaced letters on their interpretation of [“Last Year at Marienbad“]?… [P]eople identify with it so strongly that thy get upset if you don’t like it — as if you were rejecting not just the movie but them…. Antonioni’s new mixture of suspense with vagueness and confusion seems to have a kind of numbing fascination for them that they associate with art and intellectuality, and they are responding to it as their film — and hence a masterpiece.

Kael also wondered: “Was there ever a good movie everybody was talking about?”

After Antonioni’s death last week, Dennis Lim wrote at Slate.com (“The laugorous, achingly hip films of Michelangelo Antonioni“):

While Bergman’s status in the pantheon has diminished, his reputation somewhat dented by overexposure and caricature, Antonioni is very much back in vogue. […]

If Antonioni’s movies have proved more resistant than Bergman’s or Fellini’s to the tides of fashion, it’s partly because they were often so achingly hip to begin with, so unmistakably adorned with the trappings of their period that they now serve as vintage time capsules.

One of the most thought-provoking comments I came across last week, written before the news of Antonioni’s death, was from Michael Atkinson, who wrote, “Today, we are aswarm with Antonioni imitators, but no one seems to want to be the new Bergman.” Andrei Tarkovsky was influenced by both Bergman and Antonioni, but he died in 1986. Wong Kar-Wai certainly owes significant debt to Antonioni, and Lim also cites his impact on filmmakers from “Béla Tarr in Hungary to Abbas Kiarostami in Iran to Carlos Reygadas in Mexico to Jia Zhangke in China, Carlos Reygadas in Mexico to Jia Zhangke in China.” There’s Robert Altman (who also adored Fellini), Wim Wenders, Bernardo Bertolucci, and Steven Soderbergh, too. Dennis Cozzalio adds Brian DePalma, Gus Van Sant, and Peter Weir. The Big Guys also influenced one another: Anybody fail to see some “L'Avventura” in the wide-screen spaces and architectural compositions of Godard’s “Contempt“?

Glenn Kenney (“Thirteen Ways of Looking at Ingmar Bergman”) responds to Atkinson, saying that “nobody can be the new Bergman.”

Unlike a lot of younger filmmakers today, Bergman was a highly, richly cultured individual. He knew the Bible backward and forward, Shakespeare too; fine art, music, and so on. All of his knowledge did more than inform his work—his work is suffused with it, it gains much of its texture and heft from it. Of course, Antonioni is similarly cultured, but his depth in this area doesn’t play so much upon the surface of his work; it motivates the form, rather than thickens it. Today’s young filmmakers aren’t, for the most part, as polyglot. For a lot of them, all the culture they’ve got is film. And Antonioni’s got a signature style that’s accessible to them, and seems imitable: shoot some architecture and negative space, have characters disaffectedly utter banalities, and you think you’ve got it. To emulate Bergman, you’ve got to know what he knew, and knowing that…go on to be yourself.

Peter Nellhaus noted that in user polls at IMDb, 46 percent of (random) respondents report never having seen a Bergman movie, and 64 percent have never seen an Antonioni movie. Which prompts me to wonder: Who are these people? Maybe they’re young and just beginning their movie education/experience (I hope that’s the case). But, despite Rosenbaum’s mysterious contention, Bergman’s best-known films are all available on Region 1 DVDs (I count 22 titles on the first page of Amazon.com’s results for Bergman, alone including “Monika,” “Through a Glass Darkly,” “Winter Light,” “The Silence,” “The Seventh Seal,” “Wild Strawberries,” “The Virgin Spring,” “Persona,” “Scenes From a Marriage,” “Fanny and Alexander”); and Antonioni’s famous trilogy — “L’Avventura,” “La Notte” and “L’Eclisse” — are also available, the first and third in two-disc Criterion editions. “The Passenger,” starring Jack Nicholson, was released with much fanfare in a restored DVD version just last year.

These movies are easier to see now than they have been since they were originally released.

If you’re at all interested in the major new art form of the 20th-21st century, being unexposed to Bergman or Antonioni is like someone interested in 20th-century music being ignorant of Stravinsky or the Beatles, or someone interested in 20th century painting having never seen a Jackson Pollack or Andy Warhol. It’s not possible! To say you’ve never seen any of their movies is to say you’re not very serious about movies. You don’t have to like ’em, or even “understand” ’em, but you can’t be unexposed to them.

While you’re waiting for the discs to arrive, check out the round-ups of viewpoints on Bergman and Antonioni at David Hudson’s essential Greencine Daily blog. Then tell me we’re not going to continue passionately debating these guys for a long time.