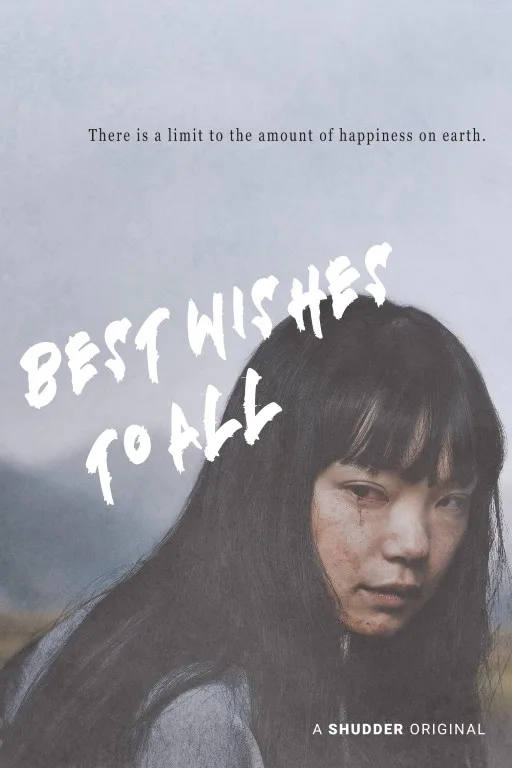

Despondent and gloomy even while it’s against a backdrop of bucolic beauty, director Yûta Shimotsu’s debut feature “Best Wishes to All” is the type of unsettling, high-concept horror film that knows exactly what it wants to be and executes it with unforgiving verve. At times, it struggles to mix its eerie imagery and indicting allegory into a satisfying whole. However, that hardly takes away from its disturbing pleasures or the prescient messages Shimotsu wants to burrow under his viewers’ skin. Weaving a story about how our happiness is literally contingent on another’s suffering, “Best Wishes to All” is a modern parable for our capitalistic society, where our only hope for achieving contentment is to exploit before we’re exploited.

Shimotsu expands his 2022 short film into a full-length project here, focusing on a nursing student played by Kotone Furukawa (all characters in the film go curiously unnamed) who leaves Tokyo to visit her grandmother (Inuyama Yoshiko) and grandfather (Arifuku Masashi) in the countryside. When we meet Furukawa’s character, she holds an effervescent–but not naive–optimism about the world. She knows society can be unforgiving, particularly for the most vulnerable. She sees her vocation as a way to help people and a small way she can contribute to the world’s healing. Her trip to her grandparents is an outpouring of her servant’s heart and a testament to her belief in the power of interdependent care.

Once she arrives at their place, she’s disarmed by both their cheery demeanor and strange behavior, and it’s during these first few nights with the trio that Shimotsu crafts some of his most unsettling sequences. Take a moment where her grandparents, mid-dinner, begin to noisily oink in unison after eating pork belly and refuse to stop or answer why they did so, or when Masashi’s grandfather character, frozen in place, stares at the ceiling with his mouth agape as if he’s silently been possessed by a ghost. Not all of the set-ups are as effective, such as a moment where Yoshiko’s grandmother character, standing in a hallway shrouded in darkness, rushes and begins hitting a door repeatedly; the whole thing comes off as comical and bumbling rather than frightening.

Their granddaughter takes these idiosyncrasies in stride because, in between their spasms, they ask the usual grandparent questions, like whether she’s happy and is enjoying her life. It’s all deceptive mise-en-scène before Furukawa’s lead discovers that her grandparents are housing and torturing an unknown man in their upper room. Her revelation coincides with the arrival of her parents and younger brother, but rather than acting surprised, they respond with nonchalance and sheepishness. “Maybe we should have told her sooner,” her father responds wryly to her daughter’s horrified face.

The particular rules of this devilish arrangement are not fleshed out in further detail, only that for their family to experience true happiness, it requires that someone be decidedly unhappy. The other information we’re given is that this practice is as ancient as it is ubiquitous. Save for a classmate (Koya Matsudai), Furukawa’s character reconnects with–who is seemingly the only unhappy person in their town–she realizes that everyone in her grandparents’ town has made a similar bargain, each with their victims-soon-to-be-skeletons in their closet.

The rest of the film follows Furukawa’s character’s grappling with this reality, where she wrestles with the fact that her bliss came at the cost of another person’s autonomy. Here’s where Shimotsu’s film shifts to its more allegorical mode, and it’s arresting to witness the ways he finds to fuse genre tropes with his critiques. Making houses feel haunted and open spaces feel like they’re rife with unseen danger should be the bread and butter of any horror director, but what makes Shimotsu’s presentations of the grandparents’ home so haunting is thanks to the revelation we witnessed prior. Like Furukawa’s lead, we know that the cost of such quiet comes with blood and that the happiness of this cheerful town is built on the foundation of weeping and gnashing of teeth.

It’s chilling to see the people in the town move with such normalcy, a note on the ways cruelty and indifference have become in many ways just like the air they breathe or the miso they stir in their soup. There’s a stomach-churning sadism we witness as not only does the protagonist’s family seem unbothered by this set-up, but they take a perverse pleasure in inflicting harm on their sacrificial lamb. Shimotsu paints a depressing picture of the family as having all but given up on change; the only way for them to live with themselves and overcome any guilt is to take pleasure in the macabre. It’s the same choice, of indifferent acceptance or hopeful rebellion, that befalls Furukawa’s character.

In her introduction to the film for the 12th edition of the Chicago Critics Film Festival, RogerEbert.com contributor Katie Rife shared how directors like Shimotsu and Ryota Kondo are young directors who were influenced by the ‘90s and ‘00s J-horror movement. This meant that for such directors, their exposure to the genre consisted of hallmarks like “creepy kids, damp atmosphere, techno-paranoia, and an oppressive sense of dread.” Many of them also have been mentored and had their projects produced by Takashi Shimizu (of “The Grudge” fame). It’s fascinating now to see how “Best Wishes to All” (which Shimizu did produce) not only deploys some of those early tropes but recapitulates that era of J-horror’s fears in a contemporary way.

For all its grotesque imagery, “Best Wishes to All” is notably elegiac. Furukawa’s character is told that kindness and caring for others, like training wheels or baby teeth, are just things that you grow out of. It’s not just foolish, but childish not to partake in this dark ritual. What’s presented to her is that there’s no “debating” that this is the way of the world; one can accept the system in community or face a painful and isolating expulsion. Shimotsu, in turn, turns that choice back on us. To deny ease of exploitation is a decision to make not just once, but every waking moment—best wishes to all who dare to dream otherwise.

Best Wishes to All is now streaming on Shudder.