“The Emigrants” isn’t the kind of movie we used to be shown in grade school, a movie all about the tired and huddled masses and Samuel Gompers and melting pots.

No, it tells a simple story (and one closer to the truth, most likely) about European peasants caught in an impossible situation. Their land is poor and their crops scarce, their greatest efforts only force them more deeply into debt, and the social system will not allow them to better themselves. Eventually they arrive at a reasonable course of action: They will go to America and see if things are not better there. Their dream is naive, desperate and brave – all at the same time. Nobody has told them the streets are paved with gold (and they are too filled with Swedish common sense to believe that, anyway.) But they have heard stories about the prosperity to be found in America, and it seems as if every mother has a son in Minnesota who owns 100 acres of land. That must have sounded impressive to anyone who had not seen the Minnesota of 150 years ago.

Two boys, bound under contract for a year to a stern and sadistic farmer, read a booklet about the Promised Land: “Even the slaves have a higher standard of living than most European peasants. They are allowed to own their own chickens and market the produce themselves.” “I’m going to sign on as a slave,” one of the young boys exclaims, his eyes alight with the wonder of his opportunity.

And later, on board a paddle-wheel steamer that is taking them through the Great Lakes to Minnesota, the emigrants in steerage look up in admiration to the rich first-class passengers on the upper deck. “I thought you said there were no commoners and gentry in America,” one says.

“I said there isn’t a CLASS system,” the other explains. “The way it works is, those people who have been here long enough are already rich. We’re still poor because we just got here. It takes a little time.” The reasoning seems sound as a bell, and Jan Troell’s film masterpiece is made up of dozens of moments like this, moments when hope and reality clash, and the new Americans take measure of the actual situation they find themselves in. There’s not a one of us – not even the Indians, who came first – whose ancestors didn’t come to this continent from another, and yet we so easily forget this most historic of all movements of people. We think we were here always.

Troell’s epic film, more than 2 1/2 hours long and infinitely absorbing and moving, is based upon “Upon a Good Land,” the best-selling series of Swedish novels by Vilhelm Moberg. At nearly $2 million, this is the most expensive and ambitious Swedish film ever made and one of the handful of foreign films ever to be shot partly on location in America. (Troell used the Great Lakes, Minnesota, northern Wisconsin – and Galena.) It tells the story of Swedish immigrants but it might as well be about any group of people. The voyage would have been just as long, the illnesses and deaths just as heartbreaking, the spirit as indomitable. Troell is considered perhaps the best of the post Bergman generation of Swedish filmmakers; like his contemporary Bo Widerberg (“Elvira Madigan,” “Adalen 31”) he has a feeling for the historical past, and for the meaning and beauty of ordinary lives. Troell’s first film, “Here’s Your Life,” won our 1967 Chicago Film Festival, and his “Ole Dole Duff” won again in 1969 (he shares with Peru’s Armando Robles Godoy the distinction of having won twice). Both films dealt with common life in Sweden, and “Here’s Your Life” was an extraordinarily beautiful story of a young man’s coming of age in the years before World War I. It is said that Moberg – who had refused to have his novels filmed – saw this work by Troell and decided he had found, at last, the right director.

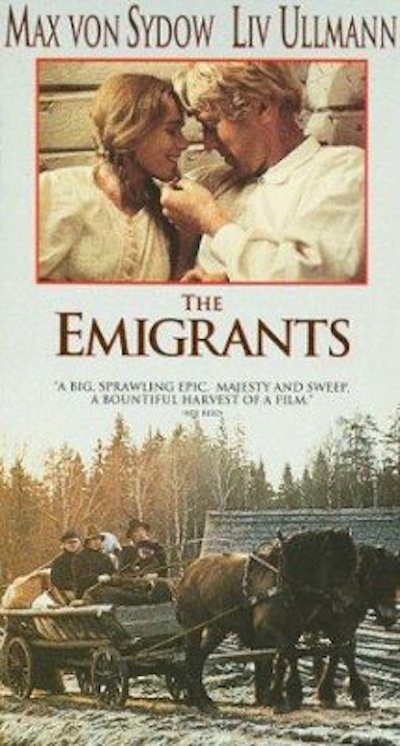

Troell, in turn, has found the perfect casting for his emigrant couple in those two splendid Swedish actors, Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann. With the rest of the excellent cast, they bring a purity, a grit and a depth of purpose to their roles that, we feel, the original settlers must have had.

“The Emigrants” is a special film in that it’s Swedish and yet somehow American – in the sense that it tells the story of what America meant for so many millions. When it was over the other evening, the audience applauded; that’s a rare thing for a Chicago audience to do, but then “The Emigrants” is a very rare film.