I turned 50 today. Here’s an account of my life, by way of movies and moviegoing. The titles of movies have been arranged chronologically by release dates, but the memories themselves are not sorted that way.

This is not a list of what I think are the best films of any given year. It’s a kaleidoscopic, fragmented biography of sorts.

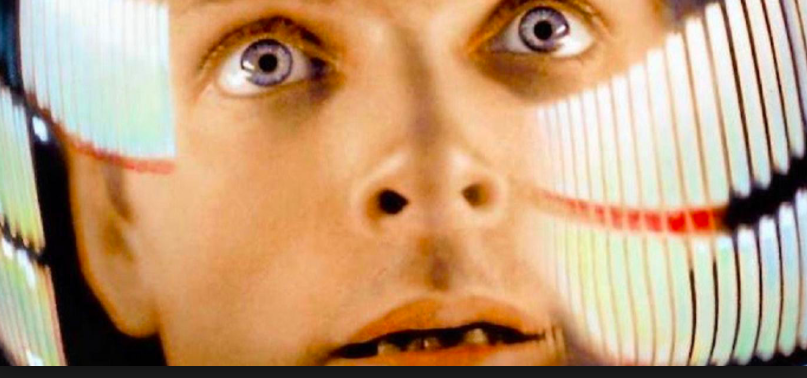

1968. “2001: A Space Odyssey”

I couldn’t possibly have any memory of seeing this movie, because it came out 10 months before my birth. I include it because it’s the greatest science fiction film I’ve seen (and the science fiction film I’ve seen more often than any other) and also because I’ve been told I was conceived after my parents saw it. I recently asked my dad for confirmation on this and he said that he couldn’t be 100% sure, but they definitely saw the film around that time, and they were high as kites. It was the sixties, and they were musicians.

1969. “Midnight Cowboy”

Whenever I think of this film, I think of the classic Harry Nilsson theme song, the poster of Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman walking together, and how my first wife Jennifer, who worshipped New York City many years before we actually moved there, used to re-watch it periodically, because she loved the gritty footage of Times Square and appreciated the compassion and hard irony of the film’s portrait of characters living in the margins. Her favorite moment was where Voight walks along the street on a cold winter day and spots Hoffman sitting in a coffee shop. They make eye contact and instinctively smile at each other, then remember that they’re supposed to be feuding over something.

1970. “Patton”

My late stepfather, Bill Seitz, made the family watch this movie every time it was on TV, which was quite often in the ’80s. He was a right-wing Republican who had once been part of Ayn Rand’s original Objectivist study group in New York in the 1960s. The last time we watched it together was on the eve of Operation Desert Storm, and there, too, he was convinced that the film’s version of Patton “had the right idea” about war and violence. Bill had been in the army during peacetime in the 1950s, but he was a gun fetishist who had a firearm in every room of the house in case of a home invasion. I later learned that Richard Nixon watched “Patton” in the White House and then decided to widen the Vietnam War into Cambodia.

1971. “Harold and Maude”

This is actually three memories. The first was seeing it on cable in high school, probably around 1985, and being fascinated by the gap in age between the suicidal teenage hero and a woman old enough to be his grandmother, as well as by the way the film moved so easily between wistfulness, slapstick, and depressive fogginess (all unified by Hal Ashby’s direction and editing, and Cat Stevens’ songs).

The second memory is of editing a video essay comparing Wes Anderson‘s films and Hal Ashby’s in 2009, shortly after breaking up with the first serious girlfriend I had after Jennifer died suddenly in 2006 of undiagnosed heart problems. The video was part of a series, and I spent several days on the Ashby chapter. Jen and I had been together since college, and I’d never really broken up with anybody that I’d been with for a period of years, so this was a new and crushing experience for me—so devastating that for a long time, I didn’t want to hear the sound of Cat Stevens’ voice.

The third memory is of going out for a date with a different girlfriend a few years after that, and leaving my daughter Hannah at home to babysit my son James. She had just turned 13 and was a precocious, film-loving kid. I told her she could watch any DVDs from my collection that she wanted, regardless of rating, as long as the movie was one that she hadn’t seen before. When I got home, she was asleep in bed, and my “Harold and Maude” DVD was still in the player. I wrote an essay about the film for the 2012 Criterion release, which you can read about here.

1972. “The Godfather.” My only long-term girlfriend in college, Jennifer—later my aforementioned first wife—was obsessed with this film and its sequel. A new entry in the series, “The Godfather, Part III,” came out in December, 1990, when we were still working on our degrees Southern Methodist University in Dallas and living together in a tiny efficiency apartment. We decided to hold “Godfather” parties where we’d invite friends over to watch the first two on VHS cassette while eating Italian food, then go out and see the third installment in a theater.

The problem with this plan was that after eating Italian food all day, you tend to fall asleep when you’re sitting in a cool, dark theater in the evening, no matter how amped you are. So it took us a third attempted viewing by ourselves before we could actually get through the third “Godfather.” (For the record, I don’t think it’s a bad movie, just problematic, and probably fatefully compromised before the cameras even started rolling—I also think that, all things considered, there are worse crimes against cinema than having made the third best “Godfather” movie.)

My fondest memory of this screening experiment was our mutual friend Jill Bettinger, who hadn’t seen any of the films, gradually picking up on the rules of the Corleone universe. By the time we got near the end of “The Godfather, Part II,” Michael told Fredo not to run away from the New Year’s Eve celebration in Havana because he had a car waiting to take him to the airport. Jill yelled at the TV, “Don’t get in the car, Fredo!”

1973. “The Exorcist”

I was much too young to have seen this in a theater when it was first released, but I saw it on TV years later, on ABC, when I was in the fifth grade, and it still scared the crap out of me, even though it had been severely edited for television to remove most of the violence and perversity as well as all of the profanity. (“Your mother sews socks that smell!” the devil-possessed Regan croaked.) For a period of about a year, I worried that each time I went to sleep, I might get possessed by Satan. I wasn’t particularly religious as a child, and I’m still not. Any movie that can put the fear of god in an agnostic is one that’s fully in command of every aspect of cinematic craft, for better or worse.

1974. “Blazing Saddles“

Another one I was too young to see on first release. Saw it on network TV later with the cuss words bleeped out, along with the flatulence in the bean-eating scene; the racial slurs were left in, for some inexplicable reason. Still one of my most-quoted movies, although only in the company of people who know me very well. I’ve been known to exclaim, “Mongo! Santa Maria!” for no apparent reason. One of the reasons this film has held up so well, and other edgy ’70s and ’80s films haven’t, is that the ultimate target of every gag is ignorance and bigotry.

1975. “Logan's Run.” My parents divorced when I was seven and packed me off to live with my maternal grandparents in Kansas City, Kansas. This was the first movie I remember seeing in a theater with my grandparents. I asked them to take me because I thought the poster made it look cool. I don’t remember much about watching it the first time, except that there was a lot of nudity in it, which made an impression on me because little kids weren’t supposed to see that.

1976. “King Kong.” My childhood obsession with monsters was amply rewarded by this remake of the 1933 classic, which starred Jeff Bridges, Jessica Lange, Charles Grodin, and an ape that was, variously, a miniature, makeup artist Rick Baker in a suit, and a full-sized, audio-animatronic head, shoulders, and hand. In a 2008 interview with Keith Uhlich, I talked about the biographical significance of this movie, and even more so, a making-of book that I ordered through the Scholastic Book Club, which explained the entire production in language a kid could understand. “All things considered, if you look at it now, it’s not a very good movie,” I told Keith. “I mean that’s putting it mildly. But it was fascinating to me and it sparked something in me. And I found myself looking at movies, not just watching movies, but looking at movies and thinking, ‘How did they do that?’”

1977. “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” My dad came to Kansas City to visit over Thanksgiving in 1977 and took me to see this film. I already knew everything that happened in it because I’d collected all of the trading cards. Of course if you were a kid of any age who was alive at that time, “Star Wars” was the biggest deal of the movie year, and the biggest thing ever, maybe. But this one made a more powerful and immediate impression on me, maybe because it deals with abandonment and people who are missing and then return, and because it was about a family that splits up over what amounts to an artistic vision (though in the film, the questing heroes make visual art, whereas my parents made music—and in their own ways, they were both the Richard Dreyfuss character).

1978. “Watership Down.” I wrote about this film in context of the recent Netflix miniseries version. I read it in elementary school shortly before the movie came out, and the film was shown in the school auditorium the following spring, when my English teacher was having his kids read Richard Adams’ novel. The teacher arranged for a trans-Atlantic phone call with Adams during which a small group of particularly precocious kids each got to ask him one question. Mine was about whether the story of the novel was really about World War II, with the rabbits standing in for Jews fleeing genocide (the subject was on my mind because I’d watched the miniseries “Holocaust” on TV a few months earlier).

Adams laughed and said it wasn’t consciously a Holocaust analogy, but said that he understood why I would’ve seen that in the book, and added that he did take aspects of the tale from his own World War II experience. He did not go into details at the time, but as Lisa Rodriguez McRobbie wrote in a 2012 piece about the book for Mental Floss, “Lieutenant Richard Adams commanded C Platoon in 250 Company’s Seaborn Echelon, and, as he wrote in his autobiography, he based Watership Down and the stories in it around the men of the 250 Airborne Light Company RASC—specifically, on their role in the battle of Arnhem.”

1979. “The Muppet Movie.” Still probably the best of the Muppet films, and the one with the best music, from Kermit’s curtain-raising “The Rainbow Connection” through Gonzo’s “I’m Going to Go Back There Someday.” I will always associate that second song with leaving Kansas City to go back to live with my mother in Dallas in May, 1980, because it was the last song that my class sung during the year’s final choral recital, and even at the time, at age 11, I remember thinking that if this were a movie, that would be the song they’d play at the moment when the hero left town.

I did a video essay with fellow Muppet enthusiast Ken Cancelosi about the collaboration between Jim Henson and Frank Oz, titled “Henson & Oz,” for the Museum of the Moving Image website. It was made almost eight years ago, though, so you’ll need to allow a Flash plugin to watch it. At some point I’ll upload the original to Vimeo.

1980 “The Empire Strikes Back“

Still the greatest of all “Star Wars” movies, and personally resonant for me because it was the last movie I saw in Kansas City before moving back to Dallas to live with my mother and stepfather. The second-to-last image, it seemed, told my story, in a way: Luke and Leia on the bridge of a rebel star cruiser, watching the Millennium Falcon fly off in search of the kidnapped Han Solo, and contemplating their uncertain future.

1981. “Raiders of the Lost Ark“

Probably the first movie that made me realize that films were directed—that they were the product of individual sensibilities just like music and painting, and that Steven Spielberg was an absolute master at manipulating the audience. I wrote about this epiphany here.

1982. “The Thing”

Saw it with several middle-school friends. We were all into horror movies. We were completely unprepared for what John Carpenter had in store for us. This was also the first time I can remember being angry at a film’s critical reception. Most reviews at the time were mixed to negative. History has been very kind to it—a lot of people now consider it to be Carpenter’s best—but at the time, it was widely considered to be too bloody, too grim, too much. That same summer, I remember being irritated by negative reviews of other films I adored, including “Blade Runner,” “Rocky III” and “Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid.” I guess this was the year when I started reading a lot of film criticism in different outlets, otherwise how would I have known what the consensus was? (For a fuller consideration of “The Thing,” click here.)

1983. “Return of the Jedi“

The first “Star Wars” film that disappointed me. I watched it again recently and liked the throne room scenes, the big space battle, Lando’s final run, and the Rancor’s trainer weeping after Luke kills the monster. But I found the rest listless, particularly at the level of performance (Ford in particular was often terrible in it, though the script didn’t give him much to work with). And I found the brother-sister reveal contrived—seemingly an attempt to top “I am your father” in “Empire,” and more nonsensical, because we’d seen Luke pining after Leia for two movies, without any narrative architecture preparing us for it (except maybe the telepathic conversation at the end of “Empire”—though it was never established if Leia was uniquely suited to receiving Luke’s messages or if she was just the person he happened to send it to).

This was pretty much the same reaction I had the first time I saw it, at age 14. Back in 1983, I was depressed that I didn’t love the movie, because I’d spent the preceding six years thinking about George Lucas’ world and consuming various adjacent products, including novels and comics. But I also felt that it would be dishonest to convince myself that I liked the film when I knew I mostly didn’t. I’ve re-evaluated a lot of movies over the years, liking things I used to hate and hating things I used to like, but this is a rare case where my basic verdict remained unchanged. Not counting seeing bits and pieces of it on cable, this is the film from the original trilogy that I’ve seen the fewest times all the way through — three, total, versus probably 20 for the first one and 10 for “Empire.” In retrospect, seeing “Jedi” for the first time was another moment that set me down the road towards being a critic.

1984. “Amadeus.”

The first costume drama that I remember being completely enthralled by. Directed by Milos Forman from Peter Schaffer’s screenplay (and based on his play) it was rude, goofy, suspenseful and ultimately sad, and the combination of raunchiness and what you might call “office politics” was new to me (even though it had been done in earlier films that I hadn’t yet seen). I’ve never written a full length piece just about “Amadeus,” but I did mention it in a Rolling Stone piece about other biopics of geniuses, which you can read here.

1985 “Lost in America“

As I wrote in a recent piece for Rolling Stone, this is the great America economic horror movie, although I didn’t necessarily understand it that way at the time: “The Desert Inn does not have heart. There is no Santa Claus. We have to be kind to each other. In the end, that’s all we’ve got.”

1986 “A Room with a View“

This Merchant-Ivory adaptation of E.M. Forster’s novel is the movie I’ve watched the most times during an initial release. I saw it at least 15 times the year it played at the Inwood Theater in Dallas. It got to the point where I was making friends with other people who were also obsessed with it. Some were church ladies who would come to see the 2 p.m. matinee of the film immediately after attending Sunday services.

1987 “Moonstruck“

“Snap out of it!” Another obsessively re-watched film. There were a lot that year, including “Raising Arizona,” “Wings of Desire” (a 1986 film that didn’t come to Dallas for a few months), “Broadcast News,” “The Untouchables,” “RoboCop,” “The Last Emperor” and “Prince of Darkness.”

1988 “Die Hard“

I wrote about this film at some length here, on the occasion of its 25th anniversary. This was the first action movie I evangelized about, to the point of nearly forcing people to go see it with me, particularly people who either said they didn’t like violent movies or had watched the first trailer and written it off as “Rambo in a Building” (which is how “Die Hard” was sold to the studio originally, and not an entirely inaccurate summation). The last person I saw it with during its original theatrical run was my college friend Barry, who kept insisting that he had no interest in seeing the star of “Moonlighting” run around with a machine-gun. We borrowed a friend’s car and drove to Valley View Mall to catch the final showing in Dallas on a Thursday night around 9 p.m. By the time the final credits rolled and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony kicked in again, Barry turned around and yelled to the projectionist, “Crank it!” The projectionist cranked the volume, then gave us a ride to the car afterward.

1989 “Do the Right Thing”

Spike Lee‘s third film was aesthetic and intellectual dynamite, although much of the media at the time only saw it as dynamite. This was the first film whose reception I followed simultaneously on the editorial and arts pages of newspapers and magazines. A lot of people seemed concerned that “Do the Right Thing” was going to incite riots, but none of them seemed disturbed by the institutionalized racism and state-sponsored violence (police brutality) that sparked the onscreen unrest in the first place. I saw the film several times at a mostly white theater and then, after it disappeared from their marquee, at a predominantly Black theater. In the second theater, nobody looked at anybody else apprehensively or for approval, and I never overheard a single discussion about why Mookie threw the trash can through the window. Everybody knew.

This was also coincidentally the film that sparked my very first conversation with Jen, at the SMU college bookstore. The details of that conversation are here.

1990 “Goodfellas”

Now home and get your shinebox.

1991 “Barton Fink“

I’d seen and loved the Coen brothers’ previous three features, but this fourth one is the film that made me appreciate what major talents they were. That “Barton Fink” was impossible to get a handle on, and ultimately had to be accepted as it own thing, reminded me of films by directors like Luis Bunuel, Lina Wertmuller, Stanley Kubrick, and Federico Fellini that I was studying in film classes and watching in repertory screenings at the USA Film Festival and in museums. Masters were in our midst, and we were only beginning to appreciate them.

1992 “Malcolm X“

Jen and I saw this for the first time at the NorthPark III-IV theater in Dallas, now defunct. It was opening day, the first evening showing, a gathering of the city’s biggest Spike Lee fans, people who were starting to understand him the way they understood their friends. When Spike’s patented people-mover shot appeared onscreen during the climax, after three hours of the director not using it, the audience burst into applause that was simultaneously mocking and sincerely appreciative.

1993 “Short Cuts“

Of all the great films that I saw that year, this is the one I think about the most: Robert Altman’s mosaic of stories about Los Angeles, based on short fiction by Raymond Carver. My Dallas Observer review at the time was mixed, though now I really can’t justify that verdict; any flaws the film has (such as the Annie Ross-Lori Singer storyline, the only one not based on a Carver story) seem negligible compared to the vastness of its vision and the intimacy of its characterizations. (It’s not online, but you can read it if you own a laserdisc player and held onto the original Criterion DVD of “Short Cuts,” which included a supplement of print reviews, some positive, others negative, others mixed. It takes a lot of confidence to do that on a disc of your own film.)

1994 “Three Colors: Red”

Part of Krzysztof Kiselowski’s “Three Colors” trilogy, and my favorite of the three, this was an emotionally overwhelming experience, with a sense of the interconnectedness of life and human consciousness that reminded me of “Short Cuts” and another of my favorite films, “Wings of Desire.” I watched this immediately after re-watching the other two films in the trilogy, “Blue” and “White,” and realized that certain films are parts of a total statement and can only be fully appreciated in relation to each other.

1995 “The Usual Suspects”

I saw this one at the now-defunct Astor Plaza theater in New York City opening night, when I was in the city searching for an apartment that Jennifer and I could move into. We were leaving Dallas for New York because I’d just gotten a job with the Newark Star-Ledger and she’d just been hired as a secretary in the New York office of Fox’s syndication sales division (she previously worked in print trafficking for 20th Century Fox’s film division in Dallas, a job description that barely exists now). It was one of the more memorable moviegoing experiences of my life because, as luck would have it, I was sitting directly behind two dudes who will forever be known as “The ‘Daaaaamn‘ Guys.” I told their story on Twitter here.

1996 “Big Night“

Jen and I saw this several times in New York theaters. Every time they brought out the timpani, the crowd gasped. “Big Night” is a centerpiece in a video essay I did in 2009 about cooking and eating on film. (Same caveats apply here as for the “Henson & Oz,” linked in the “Muppet Movie” entry above. I hate how technology keeps disabling things. Watch it on a laptop or desktop and it should play fine.)

1997 “Titanic“

The first movie Jen and I saw together after the birth of our first child, Hannah. I think we saw it at Astor Plaza, the same place where I saw “The Usual Suspects” in 1995, but I might be remembering wrong. We were so excited to go to the movies again as a couple that we both might’ve overrated the actual film—but in the end, who cares? It was a big, loud, glitzy, romantic movie with a tragic and somewhat nonsensical ending (she throws the necklace in the ocean, seriously?) and it hit the spot. When Leo came down the stairs in his tuxedo, a couple hundred women and quite a few men gasped.

1998 “Saving Private Ryan“

I saw Spielberg’s World War II combat epic for the first time at a press screening in Los Angeles with my friend Robert Abele, a former SMU classmate who became a stringer for the Los Angeles Times. We were emotionally as well as viscerally overwhelmed by the movie, which rightly sparked controversy for its graphic violence as well as its sentimental valorization of America’s World War II generation. Afterward, we made small talk with a guy that Robert knew who was writing a piece about “Ryan” for some military magazine. He seemed completely unaffected by anything having to do with the characters and themes, and only wanted to talk about technical errors involving ammunition and explosives. I walked away from him without a word. Later, Robert said, “Why did you walk away?” I said, “Because I felt pretty sure that I was about to punch that guy if he said one more word about the technical errors, and he was much larger than me and could have thrown me over the balcony.”

1999 “Eyes Wide Shut”

Jen and I had developed a system for seeing movies even though we had a toddler at home. We’d pick a movie, and one of us would go to a certain showtime, then come home and relieve the other one, who would go to the next showing; then we’d discuss the movie while eating dinner and putting Hannah to bed. Jen saw “Eyes Wide Shut” first, at a 3:00 p.m. show somewhere in the West Village.

Afterward, she called me from a pay phone in the theater lobby—this was pre-cell phones, remember—and said, “I think you’re going to have to go to a later show, because I need time to walk around the city after dark. When you see the movie, you’ll understand why I need to do this.”

She came home around 8:30 p.m., and I took the subway into Manhattan to see a 9:00 show, which let out around midnight.

Then I walked around the city for a couple of hours.

She was right, it was necessary.

2000 “Dancer in the Dark”

Not Lars von Trier’s best movie, but up there, certainly one of his most original, and influential for its imagery. It was shot on regular resolution video, cropped to super-wide CinemaScope dimensions (which removed about half of its visual information, and made the image even more obviously pixillated) and then printed to 35mm film, which changed the texture of the image into some chimerical combination of film and video and gave it a simultaneously washed-out and shimmery quality. A lot of movies were being shot this way in the late 1990s and early aughts, right around the time when the industry was plotting to ditch film altogether and both shoot and project movies on video.

The critical and commercial success of this movie inspired me to become a filmmaker again, something I hadn’t done regularly since college. I also remember a comment that cinematographer David W. Leitner, who was briefly attached to a short film I never actually got around to directing, made about the editing of the movie, and of all of von Trier’s movies, something I’ve remembered ever since, and have often quoted to other people: “He always cuts a little bit before or after you think he will. The timing of every single cut is a little bit off, and that’s what gives his movies their distinctive rhythm.”

2001. The live coverage of the destruction of the Twin Towers, the attack on the Pentagon and the crash of Flight 93 overshadowed every movie of 2001, including “The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Rings,” which seemed to be commenting on the cultural moment even though it had been in production for years. I wrote about TV coverage of the attacks and its psychological effect on the United States (and the world) in a variety of outlets, including The Newark Star-Ledger (which doesn’t archive that stuff online, unfortunately) and Salon.com, in an essay titled “Image of the Decade.” I still think the attacks were timed with a perverse showman’s verve, to intensify the terror. They were conceived by someone who understood Americans’ tendency to narrativize the news and history, and their tendency to conflate movies with reality. I called 9/11 a “dirty bomb” that left lingering psychological and cultural residue far out of proportion to the physical damage caused by the attacks themselves.

I was living in downtown Brooklyn with Jennifer at the time, and I have a lot of vivid memories of that day, even though we were spared an up-close encounter with the destruction itself. One was the sound Jennifer made as she watched the second tower collapse on TV—I’ve never before heard a scream that sounded as if it had been ripped out of a person.

The other memory is of a young man in a suit and tie named Peter Elias who had escaped the collapse of the second tower and found his way across the Brooklyn Bridge and instinctively found his way back to the block where he had once lived: our block. He knocked on our door and asked if he could use our land line to call his fiancee because the cell phone circuits were all jammed. The land lines were jammed, too, and I was filing updates on the TV coverage to The Star-Ledger on a dial-up modem (which is how things were transmitted back then), so he could only try to call her occasionally. When he wasn’t trying to reach his fiancee on his landline, he was standing outside of the apartment trying her again on his cell. I went outside to talk to him during a break, and as we were making conversation, his cell phone rang. It was his fiancee.

He answered, “I’m alive.”

2002 “Gangs of New York”

There are all sorts of problems with this movie, but the richness of the film’s conception impresses me more over time. It strikes me as the fifth panel in Scorsese’s unofficial “gangs” series, which would include “Mean Streets,” “Goodfellas,” “Casino” and “The Departed.” The final shot of the New York skyline, which dissolves to a post-millennial skyline with intact Twin Towers, is still my favorite movie image explaining how such a thing could happen. The tribal mentality persists to this day, in various disguises, some more respectable than others, and Scorsese understands that on a deep level. Seeing it in New York a year after 9/11 was a staggering experience.

2003 “American Splendor”

Eleven years after Jen’s death, I married her only sister, Nancy. As we watched this movie by Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini at EbertFest earlier in the year, I realized we were responding to it as a couple at most of the same moments, and that this was going to be one of those movies that we had in common, and that meant something to us as a unit.

I felt as if I was seeing it again for the first time.

THE WES ANDERSON COLLECTION CHAPTER 4: THE LIFE AQUATIC WITH STEVE ZISSOU from RogerEbert.com on Vimeo.

2004 “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou”

Probably Wes Anderson’s least perfect film, but the one I’ve seen the most times, because its message about the healthy and unhealthy ways to process death informed my own views on the subject. I liked it the first time around, and put it on my Top 10 list for New York Press that year. But it has grown on me steadily since then. I’ve hosted many screenings of it in various cities, and am always thrilled when I encounter somebody who loves it as much as I do. I did a video essay about it with my filmmaking partner Steven Santos, as a companion piece to my book The Wes Anderson Collection.

2005 “The New World“

Still my favorite Terrence Malick film. I’ve written a lot of pieces about it, including this one. I saw the original 150-minute cut twice in theaters, and the sleeker, 135-minute cut, which was released a few weeks later, several times more. I reviewed the 172-minute Extended Cut when it came out on DVD in 2008; it’s fascinating, particularly for how it fleshes out the story as a more novelistic experience, and proves that there are an endless array of possible films hiding in the raw footage. But all things considered, I prefer the second cut. The last four minutes are the most transcendently beautiful ending of an American film since “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

2006 “Home”

I wrote, produced, edited and directed this movie. It is officially listed with a 2005 release date on IMDB, because IMDB dates films according to when they had their first official public screening, not when they were commercially released. “Home” is a romantic comedy with several sets of couples and trios and a lot of single people all trying to hook up at a party. The entire thing takes place within the span of a few hours. I call it “The $1.98 Nashville.” It’s only available on DVD now, although for a brief period it was streaming on Fandor. I might upload a high-quality version myself someday.

It’s worth seeing if you want to know what kind of a movie I would make if left to my own devices. I think there are four or five sequences in it that are quite lovely, and most of the rest is about as good as it could’ve been, considering that I had no money and didn’t really know what I was doing. The sound and the editing are the best things about it, along with several of the performances and the music. Anything that’s bad about it is my fault, not the actors or crew. I feel affectionate towards it because it’s inadvertently a documentary of the house I used to live in with Jennifer and Hannah and, briefly, our son James. A lot of the people who worked on it, and a few who are in it, have been my friends for decades. Jen produced it. The movie was released commercially in March, 2006, and played one week at a single theater in New York City. In one scene, there’s a shot of Jen sitting in a chair (I kept throwing her into the background as an extra) and you can see that she’s visibly pregnant with James.

Then Jen died in April, 2006. I didn’t direct another movie with actors in it until 2008, when I shot a short film with some of the same cast members. It’s still unreleased because I shot it on Super 16mm, but the money I’d set aside to pay for the transfer and postproduction had to be spent on my son’s surprise diagnosis of asthma. The negative is still sitting on my shelf.

If I had it to do over again, I would have named the movie something other than “Home,” because there are dozens of films with that title, and everybody who releases one thinks it’s the perfect title when it’s actually imprecise and tells the viewer nothing useful. A couple of years after the movie came and went, a filmmaker friend who liked it said I should have called it “Glad You Got This Far,” after the name of a song that’s featured prominently in the soundtrack. That’s a good title. I wish I’d had that conversation with him while I was shooting the movie.

2007 “The Simpsons Movie”

I saw this with my kids at the Court Street Theater in downtown Brooklyn, in the largest auditorium on opening weekend. The trailer and commercials had already familiarized everyone with the scene where Homer helps the pig walk on the ceiling while singing “Spider-Pig.” There’s nothing quite like hearing a couple hundred people singing that song together.

2008 “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button”

“Benjamin, we’re meant to lose the people we love. How else would we know how important they are to us?” That’s what Taraji P. Henson’s Queenie tells Brad Pitt’s Benjamin Button, who ages backwards, trying to explain death to him. Two-and-a-half years after Jen’s death, that line hit me so hard that I began crying in the theater and was unable to stop. I was sitting next to Hannah, who was 11 at the time. I excused myself and went to the men’s room, sat in a stall and continued to cry.

The door opened and I heard a janitor come in pushing a mop bucket on wheels. He heard me and said, “Are you OK in there?”

I said, “No, but it’s all right–it’s that goddamn movie that triggered it.”

He said, “Which one, ‘Benjamin Button’?”

2009 “Avatar“

I took my daughter to see this in digital 3-D. Afterward, we went for pie. She said, “Dad, what’s wrong with your eye? It’s really red.” I went to the restroom and looked in the mirror. My left eye was so bloodshot it looked like I’d been punched. I later learned that James Cameron’s science fiction epic was hell on the eyeballs of people who had severe vision problems and wore strong corrective lenses. That was the beginning of the end of my interest in seeing 3-D movies.

2010 “Let Me In“

My favorite movie of 2010, containing my favorite shot of 2010, which I wrote about here.

2011 “Tree of Life”

A religious experience, even if you don’t consider yourself religious. Also one of the only movies besides “2001” to go cosmic and abstract without just seeming like it’s trying to do “2001.” I’ve written a lot about it, and I did a video essay with Serena Bramble that ended up on the recent Criterion Disc, but this “Guide to Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life“ is a decent starting point.

2012 “Bernie“

Richard Linklater’s seriocomic docudrama brought Texas rushing back to me in a way I hadn’t experienced since the release of “Lone Star” 17 years earlier.

2013 “12 Years a Slave“

Steve McQueen’s Oscar-winner is also his best-directed movie, and the one that comes closest (in my mind) to marrying form and function. It was prominently featured in one of my most widely cited pieces, “Please, Critics, Write about the Filmmaking,” a harsh bit of prescriptive writing that lost me a few friendships. So be it.

2014 “Godzilla”

Took me back to seeing “Close Encounters” with my dad. Of all the movies not made by Steven Spielberg that try to capture the essence of his early style, this one comes closest.

2015 “The Hateful Eight“

I came out of this Quentin Tarantino movie, which I mostly hated, thinking that something truly foul was afoot in the United States, boiling just beneath the surface and getting ready to erupt, and this movie captured it but also embodied it. Reviewed here.

2016 “Cameraperson“

Nonfiction cameraperson Kirsten Johnson’s documentary tells her life story in an oblique way, free-associating through bits of footage that she’s shot over thirty years, some on location, some at home. Very little of it deals with her and her direct experience, yet by the end, we get a reasonably full picture of who she is. Obviously, it is the inspiration for this piece, and worth seeing on its own for how it exposes the imaginative poverty of so much of cinema. I told a friend afterward that seeing it was like realizing that there are twenty-six letters in the alphabet when you’ve been struggling to make do with seven or eight. It might be my favorite nonfiction film, though a few others give it serious competition. I reviewed it here.

2017 “Get Out”

The antidote to “The Hateful Eight,” and a lot of other movies, Jordan Peele’s instant classic managed to straggle two presidential eras, Obama’s and Trump’s, and speak equally to both of them. I wrote about it at length here.

2018 “Annihilation“

Alex Garland’s evolutionary psychodrama was my “2001” for 2018. I even invited people to come see it with me in a New York theater and we nearly filled the place up. A rich film that rewards multiple viewings, and that can be analyzed through a number of different prisms, always yielding valuable insights into the human psyche, and the role of art in helping to understand it. For more, click here.

That’s it for now. Enjoy the rest of your holiday.