A great film is one that can take even the most jaded of moviegoers and fill them with a sense of anticipation, wonder and sheer exhilaration. Cynicism falls away as they witness all the different creative aspects that go into making a film come together to show them sights they have never seen and tell them stories that are able to surprise while still resonating on the deepest of emotional levels. A truly great film—the kind that one can call a classic without the slightest hesitation—is one that still has the power to do that to viewers decades after it was originally released, no matter how many times they may have seen it over the years. Steven Spielberg’s 1977 masterpiece “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” which is returning to theaters for a one-week engagement to mark its 40th anniversary, is the epitome of a truly great film. Having seen it countless times over the past four decades, I went into the screening planning to devote most of my attention to how the new 4K restoration looked and found myself getting sucked as deeply into the story, the performances and the stunning visual effects as I was when I first saw it as a wee lad during its original release.

You will notice that I have not referred to it as a science-fiction film and that is because, despite that it is roundly considered to be one of the pinnacles of the genre, it is not really one in the traditional sense, as Spielberg himself states in a brief featurette preceding screenings of the film. Oh sure, it does deal with the concept of mankind’s first encounter with visiting beings from another world but it isn’t really about them per se. Until the very end, the creatures themselves are kept off-screen and their presence is only represented sporadically via mysterious lights and fleeting glimpses of their spacecraft. In fact, the film is more of a drama with conspiracy thriller overtones that looks at how those of us on Earth might react to the possibility that there really is something out there by following two parallel narratives that eventually come together in the final act.

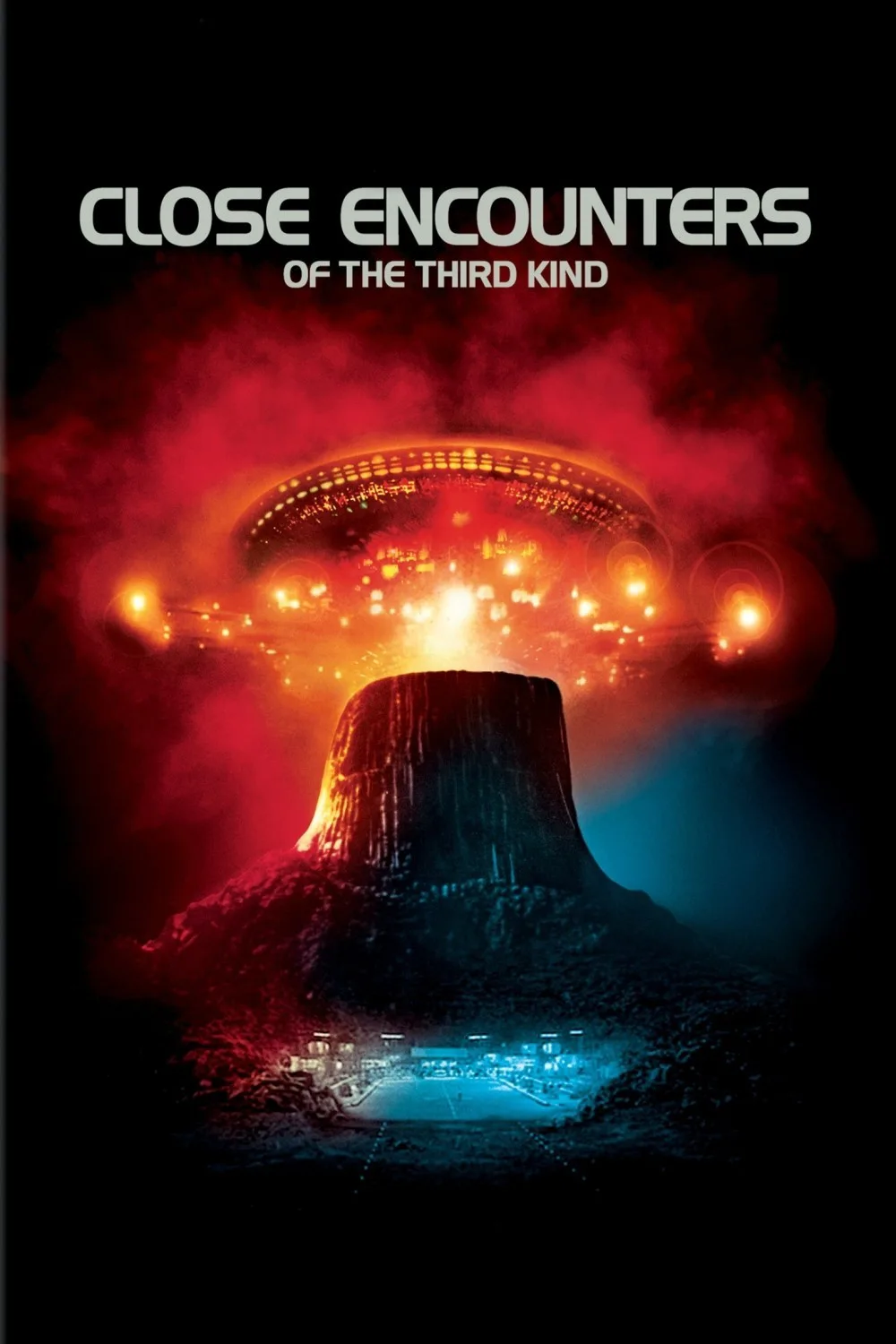

In one, a coalition of scientists led by Claude Lacombe (revered French filmmaker Francois Truffaut) dart around the world, investigating odd phenomena (such as the appearance in the Sonora desert of a squadron of planes missing since 1945) and working on a way of communicating with potential visitors based upon musical intonations. When they try it out, they do get a response that turns out to be coordinates for an apparent landing at the imposing Devil’s Tower monument in Wyoming. While Lacombe and the other scientists prepare for their arrival, the U.S. military tries to keep a lid on the story by launching a massive cover-up involving fake reports of a nerve gas spill intended to scare all civilians out of the area.

In the other, we meet two Indiana residents whose paths cross and whose lives are changed forever after apparently encountering UFO’s. The first is Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss), an ordinary family man and electrical lineman who is sent out to investigate massive power outages in the area and who has a very close encounter along the way. A dreamer by nature—the kind of guy who is far more excited by the prospect of seeing “Pinocchio” than his kids—Roy is driven to distraction by his experience and the visions in his head of things he cannot adequately explain. It gets to the point where his less-than-sympathetic wife (Teri Garr) grabs the kids and runs, while her neighbors cluck at the sight of his apparent lunacy. The other is Jillian Guiler (Melinda Dillon), a single mother whose 3-year-old son Barry (Cary Guffey) has a couple of encounters with the aliens that culminate with his abduction into the skies. Despite assurances from the government that there are no such things as flying saucers, Roy and Jillian will not be dissuaded and even after news of the alleged nerve gas spill is announced, they are still compelled to make their way to Devil’s Tower in the hopes of getting answers to the questions that are now dominating their lives.

“Close Encounters” had what could be politely described as a troubled production—many hands were employed to put the screenplay together (though Spielberg wound up with the solo credit) and the production ran over-schedule and over-budget—but it is one of the film’s considerable achievements that there is not a hint of any of that in the finished product. Even though it was only his third feature film, Spielberg directs the material with the assurance of a veteran director at the peak of his powers. The film moves like a shot yet it never feels overly rushed for a moment. It covers a wide variety of tones and emotions—ranging from silly humor and wounding drama to genuine wonder and outright terror—without ever ringing a false note. With the exception of Roy’s wife, who is perhaps drawn a little more shrill than necessary, the characters are believable and interesting, and the actors bring them all to life beautifully. (The casting of Truffaut, that most humanist of filmmakers, as the lead scientist obsessed with making contact is especially inspired—you may, as I do, prefer Jean-Luc Godard as a filmmaker but you certainly wouldn’t want him as the point man for our first encounter with beings from another world.) From a technical standpoint, the film continues to be a marvel as well—the Oscar-winning cinematography by Vilmos Zsigmond (with additional contributions from a virtual Murderer’s Row of the great cinematographers of the era) is a thing of beauty, the score by John Williams is the equal to his work on the other big genre film of 1977 and the visual effects remain among the most impressive to ever grace a movie screen.

The film is also loaded with any number of wonderful individual moments that are a pleasure to see once again on the big screen. The discovery of the aforementioned planes and a similarly long-vanished cargo ship in the Gobi Desert. The look of utter delight on Barry’s face at something that we cannot see. The sight of a vehicle pulling up behind Roy’s truck on a day street and then really pulling up. The UFO watcher on the side of the road holding up the sign reading “Stop And Be Friendly.” The old coot (Roberts Blossom) who recounts his encounter with Bigfoot. The moment when Lacombe realizes the link between Roy and the others who have come to Devil’s Tower—“They were invited.” Of course, there is also the simply spectacular finale, a sequence that should, by all rights, come off as either unbearably mawkish or kind of off-putting in regards to Roy’s attitude towards his family but somehow manages to avoid both of those traps.

If you have seen “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” before and loved it, you owe it to yourself to see it again on the big screen where it belongs and in the best of the various versions (the 1998 iteration that includes virtually everything from the 1977 original and the 1980 “Special Edition” except for the ill-advised glimpse inside the spaceship produced especially for the latter). It is as good as you remember it and serves as a reminder of a time when blockbuster entertainments were still willing to show real ambition. For those of you who have never seen it before—or have never seen it on the big screen—do not pass up this opportunity to see it the way that it was meant to be seen. Well, unless you don’t want to have a life-changing moviegoing experience this weekend, that is.