The hero of “White” tries to make money by performing in the Paris Metro. But he is not a musician, and his instrument – a pocket comb with a sheet of paper folded over it – doesn’t inspire many donations. He’s reached the bottom of the barrel, this sad sack migrant from Poland whose beautiful wife has divorced him. And he is homesick. At last inspiration strikes. A friend is flying to Poland.

Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowski) will ship himself home curled up inside the man’s suitcase.

Is this possible? Better not to ask. The movie creates a great droll comic moment when the friend lingers at the baggage claim carousel in the Warsaw Airport until it becomes unmistakable that the luggage . . . has been lost. And then there is a scene showing that the missing suitcase, with Karol still inside, has been stolen.

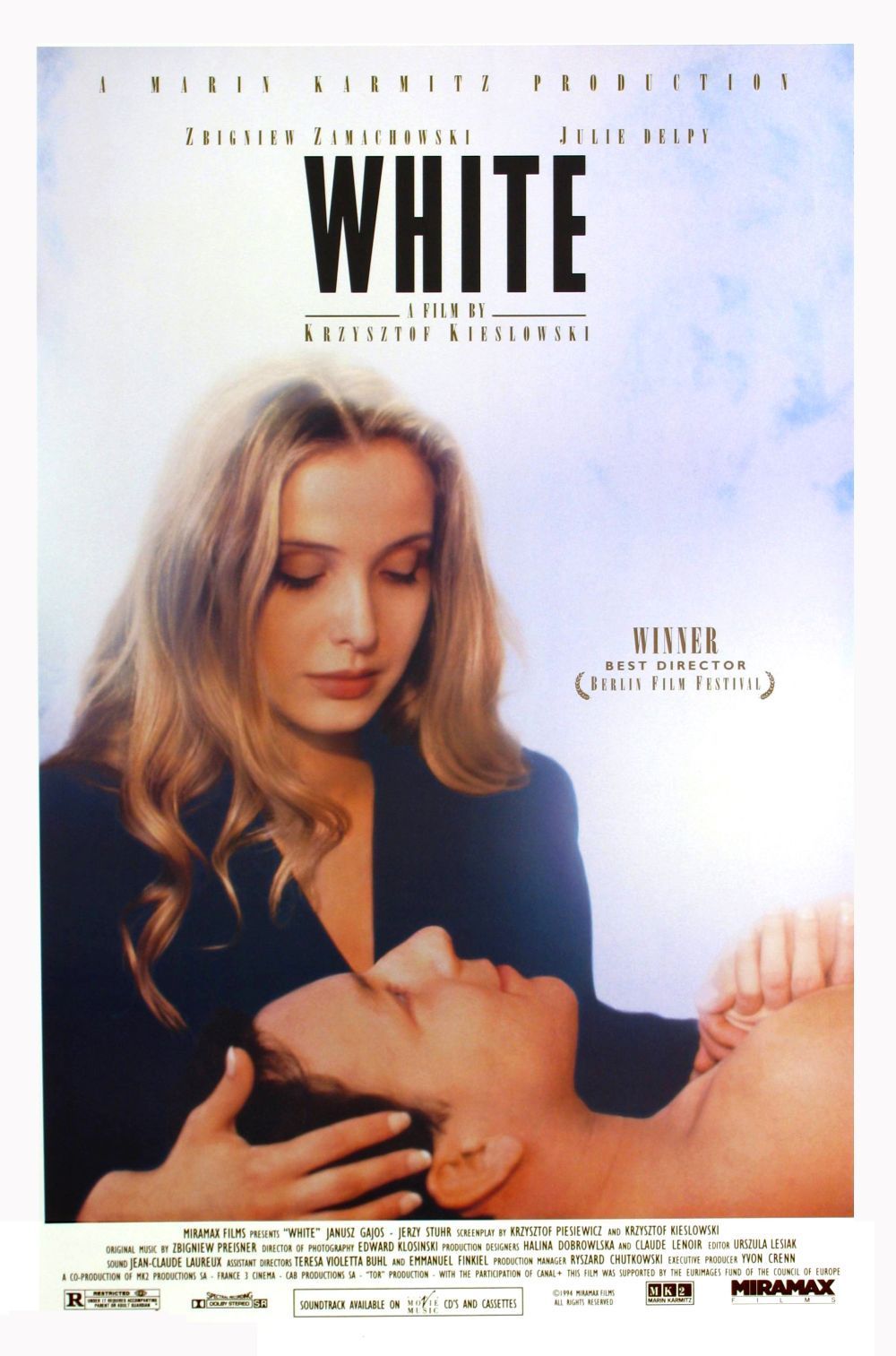

Thieves open it, are bitterly disappointed to find only a man inside, and beat him. Then they cast him aside onto a rubbish heap. It is bitterly cold. Bloody but optimistic, he surveys the grim landscape and says, “Home at last.” Depending on your state of mind, these events may sound funnier, or more painful, than they really are. Krzysztof Kieslowski directs “White” in a deadpan, matter-of-fact style that treats his strange subject matter as if it were merely factual. “White” is the middle film in his trilogy based on the colors of the French flag, coming between “Blue,” which was about a woman coming to grips with the death of her husband, and the forthcoming “Red,” about a woman whose accidental friendship with a judge leads to profound changes in her life. All of these films approach their subjects with such irony that we cannot take them at face value; “White” is the anti-comedy, in between the anti-tragedy and the anti-romance.

Kieslowski is Polish, now working in France, and in “White” he considers the new, post-communist Poland. His hero (whose name, Karol, is Polish for “Charlie,” not a coincidence), was a hairdresser before leaving for Paris, and he discovers that his brother is still operating the family salon. He agrees to do a few heads every day, and meanwhile looks around for opportunities. One quickly comes: The friend who shipped him to Poland now knows a man who wants to pay someone to kill him. A job’s a job, although this one eventually provides the most poignant moment in the movie.

A capitalist Poland provides opportunities for someone like Karol, who has soon schemed and maneuvered himself into a position of relative wealth, and begins a complicated plan to lure his former wife (Julie Delpy) back to Poland. His relationship to her is complicated; he has not been able to make love with her since their wedding day, but exactly how he feels about this, and what his plans are after her return, remain mysteries that the movie only gradually unveils.

Kieslowski allows a great deal of apparent chance in his stories. They do not move from A to B, but wander dazedly through the lives of their characters. That lends a certain suspense; since we do not know the plot, there is no way for us to anticipate what will happen next. He takes a quiet delight in producing one rabbit after another from his hat, hinting much, but revealing facts about his characters only when they must be known.

In all of his films, there are sequences that are interesting simply for their documentary content: We’re not sure what they have to do with the story, if anything, but we are interested to see them unfolding for their own sake. In “Blue,” the heroine’s pragmatic reaction to her husband’s death gave hints of greater secrets still to come. In “Red,” there are two lives that never quite seem to interlock, but always seem about to. In “White,” there is the marvelous indirection of Karol’s comeback in Poland, the way in which he becomes successful almost by intuition.

The colors blue, white and red in the French flag stand for liberty, equality and fraternity. One of the small puzzles Kieslowski sets up is how these concepts apply to his plot. As Karol deviously sets a snare for the wife he loves and hates – as he gains control of the relationship, in a way – it is hard to see how “equality” could be involved in such a struggle for supremacy. Afterwards, thinking about the film, beginning to see what Kieslowski might have been thinking, we see even richer ironies in his story.