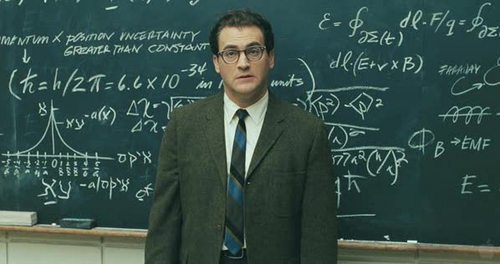

View image Jude Quinn. Bob Dylan. Mona Lisa. (Cate Blanchett.) Enlarge and see. The eyes, the mouth, the verge of a smile.

The message may not move me,

Or mean a great deal to me,

But hey! it feels so groovy to say…

— Peter, Paul & Mary, “I Did Rock & Roll Music” (1967)

The sun’s not yellow

It’s chicken

— Bob Dylan, “Tombstone Blues” (1965)

I listen to Bob Dylan for the music, not the words. I know: heresy. But it’s the truth: I listen to him for the way he sounds, and that includes the sound of the words. The literal meaning of the lyrics, or what people used to call the “message” (if one can be found or deciphered), is secondary, just one dimension of his art. In his 1960s folk-pop-culture ascendance, Dylan’s songs were scrutinized for coded messages — supposedly embedded “between the lines,” as die-hard folk-popsters PP&M put it in their satirical ditty about the superficiality and commerciality of rock ‘n’ roll music. That pop-culture illusion — that Dylan and the Beatles were sending out encrypted signals into the collective consciousness, and especially to you — is something Todd Haynes plays around with quite a bit in “I’m Not There” — a pseudo-documentary/biopic not unlike his “Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story,” but with six actors playing Dylan instead of Barbie dolls playing The Carpenters.

But before we get to that: No, I’m not at all knocking Dylan as a poet or a lyricist. (I read Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot and e.e. cummings for their music as much as anything else, too.) If Dylan’s words weren’t so satisfying to sing out loud, he wouldn’t be much of a songwriter, would he? I mean, how does it feel to sing “How does it feel?” It feels fantastic, that’s how. The black bile of those spleen-venting, “finger-pointing” songs (“Like a Rolling Stone,” “Positively 4th Street,” “Ballad of a Thin Man”) can be so cathartic. All those playfully cryptic, electric-surrealistic rhymes in “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (cue cards, anyone?) can make you dizzy with delight. A simple couplet like, “They sat together in the park / As the evening sky grew dark,” doesn’t look like all that much on the page, but you hear Dylan sing it and you feel a spark tingle to your bones.

What I mean to say is that, even if Dylan were writing in a language no one else on Earth knew (and sometimes I think that’s exactly what he means to do), his great songs would still be great songs. Take Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Do you need to know the meaning of the words in Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” to appreciate the fusion of vocal and orchestral sounds in the last movement?

O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!…

Freude, schöner Götterfunken,

Tochter aus Elysium,

Wir betreten feuer-trunken,

Himmlische, dein Heiligtum!

Deine Zauber binden wieder,

Was die Mode streng geteilt;

Alle Menschen werden Brüder,

Wo dein sanfter Flügel weilt.

Admit it! It feels so groovy to say! (Or sing.) I feel the same way about “My warehouse eyes, my Arabian drums,” and “Awop-bop-a-loo-mop alop bom bom” (by Dylan’s idol Little Richard) and “Beat on the brat with a baseball bat” (The Ramones) and “A mulatto, an albino, a mosquito, my libido” (Nirvana).

December 14, 2012