Scanners

Happy Listmas! Year is Over (If You Want It)

“‘Pan’s Labyrinth” is the best movie of 2006. Right? Of course I’m right!”

I don’t disagree at all with Andy Horbal’s list of reservations about annual critics’ “Ten Best Lists.” Andy (host of the recent, too-marvelous-for-words Film Criticism Blog-a-Thon), sizes up the obvious shortcomings of such vain hierarchical endeavors:

The interest and the function of a list depends entirely on what the author decides to do with it and how well he or she explains that decision. This requires perspective: an awareness of what such a project can reasonably accomplish and what its significance in the larger film world is. It requires, for instance, a discussion of the films from the previous year that the critic saw in relation to the films that he or she missed. It definitely requires a discussion, as opposed to merely descriptions.Couldn’t agree more. When I was a full-time daily newspaper film critic, first in Seattle and then in LA, I saw virtually everything that was released (even stuff I didn’t review), which sometimes amounted to 200+ movies a year. These days, when I’m asked to do a Ten Best list, I always feel like I haven’t done my homework, because there’s just no way I can see even the stuff I think might be ten-best-worthy — which means I’m not likely to belatedly discover any surprises I haven’t already come across earlier in the year because I’m so busy cramming during the overloaded November-December movie season, including watching DVD releases and screeners from previous months’ releases. (How the hell did I ever do this in the years before home video, I wonder?) And I always try to provide a list of movies I haven’t seen — particularly when I’ve noticed they’ve been prized by critics and friends.

But we should acknowledge that there’s inevitably an element of serendipity at work in anybody’s movie year — above and beyond the choices made by international distribution and local exhibition companies. Would I have seen Ramin Bahrani’s “Man Push Cart” if I hadn’t been introduced to it at Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival in May? Would I have come to value Doug Block’s “51 Birch Street” so highly if I hadn’t seen it at the Toronto Film Festival in 2005, presented it at the 2006 Floating Film Festival, and then reviewed it for the Chicago Sun-Times more than a year after I’d first encountered it? Would I have chanced upon Neil Marshall’s “The Descent” if Roger hadn’t suffered complications from his surgery this summer and a friend (who’d watched the British DVD release) hadn’t suggested it was worth seeing when the Sun-Times was looking for reviews? Would I have overcome my resistance to seeing “Flags of Our Fathers” (those artsy monochromatic images in the trailer and TV spots really turned me off) if I hadn’t felt I needed to see it before making a ten best list? I have no way of knowing.

To me, a ten best list is like a personality inventory — a rough sketch of who I was (and what mattered to me most) during a particular year. (I used to participate in critics’ polls for music, too, but that’s even more overwhelming.) Reviews of new releases (written on deadline) have their limitations as film criticism, and so do lists, as Andy smartly details, but at their best they can be creative and illuminating and thoughtful — almost like critical haiku. This year, I’ll be doing at least three such lists, with different sets of criteria set by the editors: for MSN Movies, for the LA Weekly critics’ poll, and for myself, here at Scanners. Most of the lists will overlap, but I hope readers will find intriguing discoveries within them.

Never have I whined as much about making a ten best list as I did in 2006 — mainly because I felt like I had so much stuff to watch — and so little time. But before I present mine, let me offer a complementary list to Andy’s (and he mentions some of these things, too):

What Can Be Good About Ten Best Lists:

1) They force a critic to try (usually in vain) to summarize what he/she values in each movie on the list. That can make for a worthy — if almost impossibly difficult — writing challenge, for those who attempt to rise to it.

2) They pique readers’ interest in films they haven’t seen, didn’t want to see (boy, was I wrong about “Flags of Our Fathers” — more on that later), or didn’t like. Of course, that depends on how open a reader is to being persuaded, but my hope is that putting a title on my list will help some people make some exciting discoveries they might otherwise have missed.

3) They’re a handy way to evaluate the critic (even more than the year — which is an arbitrary consideration, anyway). Looking at somebody’s list can tell you something about a person’s taste and values — not unlike looking at somebody’s recent book, DVD, or music purchases. I don’t know about you, but those are the first things I check out when I go to somebody’s home for the first time. I dare say it’s at least as revealing (to me) as rummaging through their medicine cabinet or underwear drawer — and far more socially acceptable.

Yes, these lists are doomed, limited enterprises. And the number ten is almost arbitrary, although there are probably solid reasons we tend to think in groups of ten — reasons that have as much to do with Darwinian development (ten fingers — handy for counting!) as they do with our Arabic numeral system (where would we be without the introduction of the symbol for zero?). As enthusiasms wax and wane, you catch up with older movies from previous years, or you revisit movies you’ve listed and found them better, worse or different than you thought they were when you made your list, you may be tempted to revise your rankings. But that’s just part of the game (and it is just a game). A ten best list is simply a snapshot of what you’ve seen out of what was released in your area during a calendar year, and what you’ve found worthwhile at the time you make the list. That’s about it.

TIFF: Monsters

Take me to the river, drop me in the water…

“The Host” (or “Gue-mool,” which sounds better) is a South Korean monster movie in which a mutant amphibious creature swims beneath the Han River, scampers among the girders beneath its bridges, prowls its sewers, and occasionally leaps onto its banks to grab some human souvenirs. The creature is just doing whatever it’s bred — or mutated — to do, but the monsters who created it, and who mischaracterize the nature of the threat, thereby making the thing practically impossible to catch or contain, are Americans — portrayed as the world’s most aggressive exporter of bureaucratic incompetence and misinformation.

In the first scene, set in 2000, a U.S. military official in scrubs (Scott Wilson — setting the funny/horrific tone for the entire movie) directs a reticent Korean subordinate to empty potently toxic chemicals into the Han. After all, it’s a big river. By the end of the film, a Senate investigating committee finds that the U.S. bungled the whole thing, and then compounded the damage by covering it up. Imagine.

Of course, the lives affected by this particular adventure in imperialistic hysteria aren’t Americans, but Koreans — in particular, the comically fractured Park family whose patriarch runs a riverside refreshment stand. On the political as well as the horror/science-fiction level, this time it’s personal. The marvelous creature (part squid, part gecko, part salamander, part sandworm, part vagina dentata, created by San Francisco’s The Orphanage), snatches the youngest Park (a uniformed schoolgirl of 13), and the rest of the clan reunites to avenge her.

Director Bong Joon-ho shifts tones with quicksilver dexterity, cannily keeping the audience (and the film) just on the edge of losing its balance and splashing into the Han. Humor turns to horror and back again in a flash, while generic requirements are both fulfilled and cleverly overturned. Even the pathos works, because it’s a little bit cock-eyed. How does the movie do all this? Must be something in the water…

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang: Deeper into Kael

“Film criticism is exciting just because there is no formula to apply, just because you must use everything you are and everything you know.”

— Pauline Kael, “Circles and Squares: Joys and Sarris” (1963)

“She has everything that a great critic needs except judgment. And I don’t mean that facetiously. She has great passion, terrific wit, wonderful writing style, huge knowledge of film history, but too often what she chooses to extol or fails to see is very surprising.”

— Woody Allen, to Peter Bogdanovich, quoted in the introduction to the book This is Orson Welles (1998)

The imminent publication of two books devoted to Pauline Kael — “A Life in the Dark,” a biography by Brian Kellow, and a collection of reviews and essays called “The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael,” both due Oct. 27 — has provided an excuse to recycle all the old arguments about her. And that’s not something I can imagine being said for many of her American contemporaries, mostly because nobody argues about them. Is there another American film critic who has inspired such a biography, published 20 years after her retirement? Does anyone still read, say, Vincent Canby, the powerful, impressively independent but rather lackluster successor to Kael’s much-ridiculed Bosley Crowther at the New York Times? (Canby covered the film beat at the Times during the height of that institution’s “make-or-break” authority from 1969 to 1993, when he switched to theater, succeeding Frank Rich.)

Some have pointed out that Kael was often wrong. Well, I should bloody well hope so. What critic isn’t? By “wrong” these critics evidently mean that she did not agree with them about which movies were good and which weren’t, or that her verdicts did not align themselves with the Judgments of History, lo these many years later. Were “Bonnie and Clyde,” “Fiddler on the Roof,” “Last Tango in Paris,” “Shampoo,” “Nashville” and “Casualties of War” really as great as she claimed? How could she be so dismissive — even contemptuous — of “La Dolce Vita,” “Hiroshima, Mon Amour,” “Shoah,” “L’Eclisse” (and all Antonioni after “L’Avventura”), “2001: A Space Odyssey” (and all Kubrick thereafter) and Cassavetes pretty much across the board? (If you don’t find at least a couple things in those lists that raise your hackles, you should be worried about the integrity and independence of your own critical values.)

Flawed

One of my favorite movie lines ever, impeccably written and delivered so that it has stayed fresh and funny for me every single day since I first heard it 30 years ago:

“We saw the new Lina Wertmuller film…. I loved it. Phil thought it was flawed.”

— Patti (Lisa Lucas), the 15-year-old daughter of Jill Clayburgh’s title character in “An Unmarried Woman” (1978) by Paul Mazursky

BTW, I’m struck that studios hardly ever make mainstream movies like this anymore, naturalistic, humanistic comedy-dramas about adults who look, talk and behave like adults — or like15-year-olds, depending on the circumstances. “An Unmarried Woman” is flawed, and I love it. (Clayburgh’s shrink still drives me up the wall, but I never doubted that she was a dead-accurate caricature. Now I think she’s hilarious; I used to just feel outrage that she was so full of shit and granola: “Guilt is a man-made emotion…. Turn off the guilt.”)

Even if the movie plays like a ’70s period picture in some ways (and it did then, too — because it was made and set in a recognizable ’70s New York movie-milieu), it’s as smart and honest and observant as ever. Almost shockingly so, given what’s passing for adult drama on big screens right this minute….

Semites and anti-Semites agree… on certain myths

Michael Chabon, probably best-known as the author of the novels “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay” and “Wonder Boys,” has an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times called “Chosen, but Not Special” — about the myths of Jewish exceptionalism that Semites, anti-Semites and Judeophiles all share: the fanciful notion that Jews possess “an inborn, half-legendary agility of intellect, amounting almost to a magical power.” Chabon argues we should acknowledge the dangers of this dumb stereotype right now.

The “widespread shock at Israel’s blockheadedness in the aftermath of the raid” on the Mavi Marmara should, perhaps, not have been so shocking, Chabon writes:

An honest assessment of Jewish history must conclude that even the collective act that might seem most tellingly to argue in favor of Jewish intelligence — our survival across millenniums in spite of constant hatred, war, persecution, intolerance and genocide — is ultimately just the same trick performed by our species as a whole (at least so far).

Heath Ledger, 1979-2008

View image Ennis Del Mar, “Brokeback Mountain.”

Rare is the performance that can honestly be called a “revelation,” but that’s what it felt like to watch Heath Ledger in “Brokeback Mountain.” Not only did he bring iconic life and nuance to the existential loneliness of Ennis Del Mar, a taciturn but complex (and conflicted) character, but for such mature work to spring from the teen-idol star of “10 Things I Hate About You” and “A Knight’s Tale” was… well, revelatory itself — the astonishing revelation of a suddenly, fully developed actor whose juvenile efforts scarcely hinted he’d be capable of such moving depth and clarity. Ledger emerged as if from a cocoon, gleaming with promise and flexing his wings.

Only two years after he received his first Oscar nomination for this iconic, star-making performance, it seems unthinkable that we should be mourning his death, at the age of 28….

Akzidenz Grotesk

“Question: how many manufactured objects did you touch this morning, between waking up and leaving your house?”

— from the “Objectified” web site

Might be easier to estimate how many non-manufactured (organic and otherwise) you made contact with. From Gary Hustwit, the director of “Helvetica,” one of my favorite films of 2007, comes the most anticipated movie of the year. For me, anyway. Spring, 2009: “Objectified.” From the official site:

About the trailer: the voices belong to Jonathan Ive, Andrew Blauvelt, Marc Newson, and Karim Rashid. The song is “I Like Van Halen Because My Sister Says They Are Cool” by our friends El Ten Eleven, from their new record “These Promises Are Being Videotaped.” And the font used in the trailer is… Akzidenz Grotesk!

That would be the lead designer of the iPod and other Apple machines, the head of the Design Studio at the Walker Art Museum, the designer of Ikepod watches, and the industrial designer Time called “the poet of plastic.” It’s a movie about… design — “our complex relationship with manufactured objects and, by extension, the people who design them.” El Ten Eleven did the music for “Helvetica,” too. And Akzidenz Grotesk is, of course, a close progenitor of Neue Haas Grotesk.

Great poster, too. As you would demand from a film about design. Click below… and find the title.

(tip: MCN)

Cave paintings: The art of ‘The Descent’

View image “The Flaming Spirits of the Evil Counsellors” (illustration for Dante’s “Divine Comedy”) Gustave Doré (1865)

“The Descent” quotes from a whole bunch of movies (and I’ll be illustrating some of those soon), but while watching it I was also reminded of some other works of art — not necessarily because the movie actually borrowed the images, but because it evokes some of the same (cold, hollow, damp, creepy) feelings I get from some of these paintings. Like this Doré engraving for Dante’s “Inferno” — a vision of a subterranean hell in which dark creatures of the imagination (and, perhaps, of the flesh as well) are let loose. As the women in the movie are warned before taking the plunge, the mind plays tricks on you down there.

In a previous post, I compared the fantastic poster with the Surrealist photograph that inspired it. After the jump are a couple more images (from Goya, Fusili, Doré) that popped into my mind during “The Descent.” (You just can’t keep this stuff down…)

WARNING: I don’t want to plant these images in your head before you see the movie, so that’s why I’m keeping them off the main page. After you see “The Descent,” though, please post comments with your thoughts. Were you reminded of these, too? Were there other non-movie associations you made? (Please remember that comments don’t go “live” immediately.)

A Fan’s Notes

I don’t usually do this (and have no intention of making a habit of it), but I wanted to share a couple of appreciations of Roger Ebert, on the occasion of his first public appearance (at his Overlooked Film Festival, aka Ebertfest) since complications from surgery last July. I know Roger doesn’t want me to turn this or RogerEbert.com into a big bouquet of flowers for him — but let’s just take a moment to celebrate his return to public life (and more reviewing!). Over the last ten months or so, many have written, in public and private, about what Roger and his writing have meant to them, and two recent notes struck me as especially eloquent.

The first is from Ted Pigeon, whose blog The Cinematic Art is a favorite of mine. (Check out his piece about critics and blockbusters, too.) Ted begins by observing:

Like so many young film lovers, I first discovered my love of film criticism through Roger’s engaging and intelligent movie reviews. His work showed me that film criticism is important, that it can be the source of great feeling and knowledge of cinema, and that criticism is essential to the advancement of cinema as an art form. It is a necesary companion to the experience of watching films for those who care deeply about films.The other piece was e-mailed to me by Peter Noble-Kuchera of Bloomington, Indiana, who recently attended Ebertfest. With Peter’s permission, I’m publishing his entire article after the jump. This paragraph really resonated with me:To know Ebert by his TV show is not to know him at all. You have to read him. He was the first film critic to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize, and one of only three ever to have been so acknowledged. He is the only American critic to review virtually every film in major release. His essays, while without the crabby flashiness of Pauline Kael’s, are marked by the groundedness of a Midwesterner, exacting writing, deep insights, and more than that, deep compassion. More than any critic, Ebert seems to understand that the movies are made by people who, with all their flaws, were trying to make a good film. He is a tireless champion of small movies of worth, and no critic has done more to leverage his influence in order to bring those films to the attention of America.As I’ve said many times before, it wasn’t until I started reading (hundreds, thousands) of Roger’s reviews when I was the editor of the Microsoft Cinemania CD-ROM movie encyclopedia in the mid-1990s that I came to appreciate what terrific critic and writer the man really is. I feel more strongly than ever about that after three and a half years as the founding editor of RogerEbert.com. He’s so very much more than the sum of this thumbs.

The rest of Peter’s report (lightly edited) below…

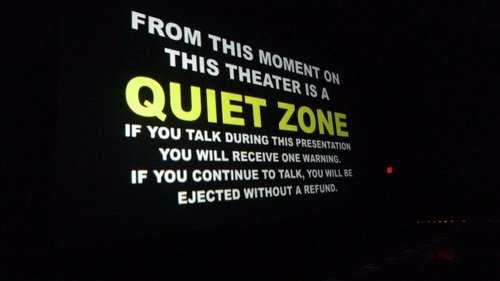

Shut up, already

The magnificent Alamo Drafthouse Cinema in Austin, TX, has the right approach. Exhibitors: take it from here. Hire bouncers. Big ones. (Photos by Mark G. Power, who is working on a movie called “Sacred Cinema,” about great places to watch movies all over the world. It sounds fantastic.)

The March of ‘The Sopranos’

Best. Line. Ever. Christopher Maltisante (Michael Imperioli), discouraging his newly pregnant wife from counting their chicken:

Remember the penguin movie, how you cried? You sit on an egg for months, one little thing goes wrong, you’re left with nothin’.

TIFF: Suicide isn’t painless

“2:37”

Born out of a suicide (a friend of the filmmaker’s) and an attempted suicide (the filmmaker’s own), “2:37” is a movie 20-year-old Australian Murali K. Thalluri never intended to write or direct. It just came out that way.

“2:37” is a suicide whodunnit. In the course of one day at school, multiple character perspectives, and a maze of Steadicam shots that virtually trace those in Gus Van Sant’s “Elephant,” we catch glimpses from the lives of several kids, any one of whom could turn out to the one in a puddle of blood on a restroom floor at 2:37 in the afternoon. (I wonder if the title isn’t also a reference to Kubrick’s Room 237 in “The Shining,” another film drawn with a Steadicam.)

Though they appear to attend a big school, each of these kids feels utterly — at times disconsolately — alone. Even when they’re surrounded by friends, the bonhomie is forced, superficial. Hey, it’s high school. (As a friend said after the screening: “I guess it just shows that Australian high school is as f—ed up as American high school.”) Emotions — big emotions — pass through like storms on any spring day. And that’s part of what Thalluri is getting at: There’s a whole catalog of After School Special subjects here (sex, drugs, other physiological and psychological problems) but any one of them, even the most trivial, could be the trigger for a suicide attempt.

The film flows naturally around its central contrivance, employing unforced performances by unprofessional actors and a visual style that uses available light to pull you into the worlds these students inhabit. The black-and-white reality-show style interviews with the kids are unnecessary, and the movie will no doubt be be met with charges of “derivative!” when compared unfavorably to Van Sant’s masterpiece. But, even if I hadn’t read the press notes (after the screening), I’d still admire the authenticity and unerring behavioral observations of “2:37.”

(Side note: “2:37” was a 2006 Cannes Film Festival selection; “Elephant” won the Palme d’Or and the Prix de la mise en scène in 2003.)

The Monument Valley: Music as film criticism

View image: “What makes a man leave bed and board and turn his back on home?”

The Drive-By Truckers’ “Brighter Than Creation’s Dark,” features a song about John Ford — and “The Searchers,” in particular. (Listen to a sample or download here.) In some notes about the songs, Patterson Hood writes: “The album closes with ‘The Monument Valley’ and the classic imagery from John Ford’s immortal masterpiece ‘The Searchers’ as the door closes on John Wayne’s walk off into the desolate beauty of a disappearing America. Ford may have been America’s greatest ever filmmaker and repeated viewings of his work reveals insights into our psyche that have never been expressed better. For me it’s an extremely personal song and it was a magical take that night in the studio. I knew that it would be the last song on the album the moment I wrote it.”

“The Monument Valley”

It’s all about where you put the horizon

Said the Great John Ford to the young man rising

You got to frame it just right and have some luck of course

And it helps to have a tall man sitting on the horse

Tell them just enough to still leave them some mystery

A grasp of the ironic nature of history

A man turns his back on the comforts of home

The Monument Valley to ride off alone

The 100 Most Acclaimed Movies of the 20th Century

View image Antonioni’s “L’Avventura” ranked in the top ten.

OK, as long as the simultaneous deaths of Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni have shaken the foundations of the pantheon and got us debating canons — again: Near the end of the last millennium, I decided to do something difficult and convoluted and thoroughly silly. On this particular occasion I determined to figure out which 100 movies were the most highly regarded at the close of the century. I think this was in late 1998 or early 1999. But more recent films wouldn’t have registered very high anyway, because I was using a larger historical sampling to compile the results.

I came up with some complex point scale for rating the movies by the awards and honors they had received, using a mixture of domestic and international, popular and critical sources. I no longer have any recollection of the formula I used, but I’m sure it was at least as complicated as the one for Coca-Cola. I know (given my personal bent) that I weighted, for example, the “Sight & Sound” international critics’ poll more highly than, say, the Oscars. And I tried to find a mathematical way to properly consider and weigh American with non-English-language films (given the restrictions and biases of some sources), and older films with newer ones. The sources I used were (in no particular order): Academy Awards, “Sight & Sound” polls (1952, ’62, ’72, ’82, ’92), the first AFI 100 list, the National Film Registry (American films selected for preservation in the Library of Congress — which had to be at least 10 years old), the Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards (1975 – ), the New York Film Critics Circle (1935 – ), and the National Society of Film Critics (1966 – ).

Although it seems inconceivable to me now, I actually put together several charts (spreadsheets!), so you could view the lists and the movies’ individual honors, not only by rank, but by director, title (alphabetically), year/decade, — and a comprehensive list of the 400+ titles that came under consideration, given my sources.

I doubt — and I hope — I will never be that anal again. But what I liked about the results was that they reflected a mix of “art films” (“The Passion of Joan of Arc,” “Bicycle Thieves”), silents (“Greed,” “Intolerance,” “The Gold Rush”) and popular titles (“West Side Story,” “Annie Hall,” “Schindler’s List”). I was also pleased with the distribution over the decades, a little more balanced than you usually see in polls: two films from the 1910s; six from the ’20s; 19 from the ’30s; 16 from the ’40s; 29 from the ’50s; 19 from the ’60s; 21 from the ’70s; 13 from the ’80s; and 14 from the ’90s (which weren’t quite over yet).

Point of interest: Bergman had three films on the list: “Persona” (22), “Wild Strawberries” (66), and “Fanny and Alexander” (84). Antonioni had one: “L’Avventura” (8).

Welles and Chaplin each had two films in the top 25. Other directors represented in the upper quarter include: Jean Renoir, Alfred Hitchcock, Federico Fellini, Sergei Eisenstein, Stanley Donen, Steven Spielberg, John Ford, Stanley Kubrick, Vittorio de Sica, Woody Allen, Erich von Stroheim, Elia Kazan, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Robert Wise, D.W. Griffith, Jean Vigo, and Michael Curtiz.

The Big List begins like this:

Opening Shots: Le Samourai

From Brandon Colvin, Out 1:

View image

View image

The opening shot of Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1967 noir masterpiece “Le Samouraï” establishes the tone of Melville’s contemplative crime film, defines its amoral protagonist Jef Costello (Alain Delon), and introduces the connections between Costello, a hired assassin, and the concept of the Japanese samurai, particularly the ronin, or masterless samurai. The nearly three-minute shot maintains a simple but wonderfully expressive composition throughout, remaining within the drab gray-blue confines of Jef’s apartment.

Jef lies stiffly on his white mattress with black polka dots in the bottom right corner of the frame. Two windows, overflowing with soft light, balance the composition by providing visual anchors in the center of the frame. Jeff’s pet bird chirps away in his birdcage, resting on a table centered between the two windows. Chairs and dressers crowd the outskirts of the frame, completing the layout of Jef’s ascetically simple, disciplined apartment. For minutes, the only sound is the constant drizzle of rain outside the windows and the intermittent whooshing of cars on the street below, punctuated by the light cries of Jef’s bird. Jef’s lights a cigarette and when he puffs, the smoke floats up softly, stagnating in the light of the windows, rolling around as if trying to escape. The completely still shot seems as if it’s attempting to emulate the frozen camera of Ozu. Jef lies with solemnity and his imprisonment in his dreary apartment is analogous to the situation of his caged bird.

View image

View image

Following the credits, text appears in the top right corner of the shot. The text reads, “There is no greater solitude than that of a samurai, unless it is that of the tiger in the jungle . . . perhaps . . .” The quote is attributed to Bushido (Book of Samurai), which Melville fabricated for the film, and illustrates the connection between Jef’s disciplined isolation and the social exile experienced by great warriors, like samurai. Particularly interesting is the connection between Jef and ronin, or masterless samurai. Ronin are noted in Japanese storytelling for their lack of morality and existential listlessness, caring for themselves above all and feeling no loyalty to exterior forces. Jef exemplifies this sort of selfish existence, which, as with the ronin, fates him to a sense of dread and, ultimately, death.

Falling: The Architecture of Gravity

or: Ways to Fall (in one or more pieces)

The first part of this little movie provides an overview of different approaches filmmakers from Buster Keaton to Alfred Hitchcock to Christopher Nolan have taken to shooting falls and/or jumps from high places. (It wouldn’t do anyone much good to fall or jump from a low place.) The second part examines, in vital but nit-picky detail, a twelve-shot sequence from “The Dark Knight” and makes suggestions for improving it, based solely on what’s already there.

TWO WARNINGS: Part I includes possible spoilers for “In Bruges” (two reminders of what makes it one of the best-directed films of the year), “The Fall,” “The Tenant” and “Infernal Affairs” — as well as not-so-spoily clips from “Vertigo,” “Superman,” “This Gun for Hire,” “Our Hospitality” and “The Dark Knight.” Some parts are a little gruesome, too. Part II delves into a brief segment of “The Dark Knight” repeatedly, shot by shot. If that places unreasonable demands on your time or patience, you’re at the wrong place on the Interwebs, so don’t subject yourself to it. There’s a little button at the lower left of the movie player that will stop it. You have been warned (and will be again).

Some notes about falling down:

Let Me In: Evil in America

“There is sin and evil in the world, and we’re enjoined by Scripture and the Lord Jesus to oppose it with all our might. Our nation, too, has a legacy of evil with which it must deal.”

— Ronald Reagan, in the 1983 “Evil Empire” speech, quoted in Matt Reeves’ “Let Me In”

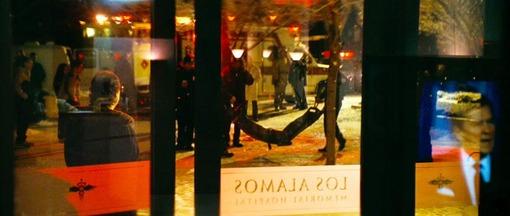

It was the pre-nuclear winter of our discontent. The Cold War was at its coldest since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Jonathan Schell’s 1981 New Yorker series about the catastrophic climatic effects of a full-scale nuclear war became a best-selling book, “The Fate of the Earth,” in 1982. By 1983, with the escalation in rhetoric between Ronald Reagan and Soviet leaders, movies like Lynne Littman’s “Testament” and Nicholas Meyer’s “The Day After” — one a bleak art-house drama; the other a network television nightmare — were dealing seriously with the prospect of American life in the wake of atomic armageddon, as if to prepare us for the inevitable.

It was one of the darkest periods in modern American history (being too young to remember the Cuban Missile Crisis, I recall only the aftermath of 9/11and the invasion of Iraq with comparable feelings of doom). And the snowy, barren landscapes of (where else?) Los Alamos, New Mexico, provide the Americanized setting for Matt Reeves’ “Let Me In,” a remake of Tomas Alfredson’s magnificent Swedish horror film, Let the Right One In” (2008).

I, Witness: A small masterpiece of voyeurism and projection

The way I see it, Jerzy Skolimowski’s “Four Nights with Anna” is small-scale masterpiece about voyeurism, movies, and the limits of perception — including what we think we can know about people from observing their behavior. The thing is, this 2008 movie never received a theatrical release in the U.S. (though it played the Cannes, Toronto and New York film festivals), and remains, incredibly, really hard to see (I ordered a Polish all-region DVD because I wanted a copy so badly). But it’s playing this weekend as part of the Museum of the Moving Image’s Skolimowski series, so if you’re in New York, here’s your window of opportunity, as it were. I wrote about “Four Nights with Anna” when I first saw it at the Toronto Film Festival, and I delve a little deeper in this piece (“I, Witness”) at Alt Screen:

“Four Nights with Anna” — such a romantic title, conjuring wistful images of a brief but passionate affair that its impetuous young lovers will cherish for a lifetime. Well, yes and no. This is a movie that very much belongs to its director, Jerzy Skolimowski, so at some point things are bound to plummet off the deep end.

As it turns out, the subversive Polish filmmaker’s 2008 return to directing (after a 15-year hiatus), is a heartbreaking romantic black-comedy in which the obsessed lover (Artur Steranko) is smitten as can be, but his beloved (Kinga Preis) isn’t conscious of their trysts. (What do you expect from the guy who got his start co-writing Knife in the Water with Roman Polanski?) Though they share precious hours together at her place, she spends them in a drugged slumber, which puts her at a disadvantage, fling-wise. OK, it’s an unconventional relationship — intense, intimate, unbalanced, mortifying — but it’s also touching and oddly sweet. You just sense from the title that it probably doesn’t have much of a future.

VIFF: Antichrist: A pew in satan’s church

Lars von Trier, maker of calculating horror comedies, is a shrewd showman — if not exactly in the classic Hollywood tradition then at least in the Barnum & Bailey one. He pleases his audiences by teasing, taunting and testing them, keeping his tongue in his cheek. I picture him as a dancing, grinning little prankster on the fringes of world cinema, alternately flaunting a streak of astringent sadism and hiding for safety behind a shield of facetiousness.

He’s also, in “Antichrist” particularly, a thudding literalist whose mock-academic ideas and images are so over-rationalized and in-your-face that (like the mysterious cry of a baby placed too far forward in the sound mix to be haunting or ambiguous) they don’t have much room to resonate. When they ought to be harrowing, they’re obvious and over-explained, which cuts them off from genuine emotion or experience. Nevertheless, “Antichrist” is a serviceable, sometimes atmospheric horror movie, until the last chapter-and-a-half when it just goes flat. By then it’s already gotten a little too much of a charge out of commenting on its own giddy morbidity, and whether the audience is laughing at it or with it doesn’t matter. Either way, the laughter is dismissive.