“There is sin and evil in the world, and we’re enjoined by Scripture and the Lord Jesus to oppose it with all our might. Our nation, too, has a legacy of evil with which it must deal.”

— Ronald Reagan, in the 1983 “Evil Empire” speech, quoted in Matt Reeves‘ “Let Me In“

It was the pre-nuclear winter of our discontent. The Cold War was at its coldest since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Jonathan Schell’s 1981 New Yorker series about the catastrophic climatic effects of a full-scale nuclear war became a best-selling book, “The Fate of the Earth,” in 1982. By 1983, with the escalation in rhetoric between Ronald Reagan and Soviet leaders, movies like Lynne Littman’s “Testament” and Nicholas Meyer’s “The Day After” — one a bleak art-house drama; the other a network television nightmare — were dealing seriously with the prospect of American life in the wake of atomic armageddon, as if to prepare us for the inevitable.

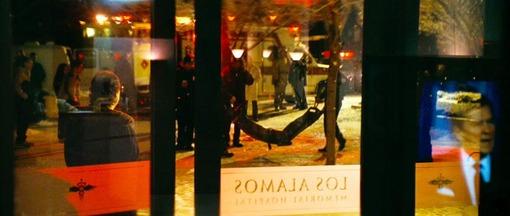

It was one of the darkest periods in modern American history (being too young to remember the Cuban Missile Crisis, I recall only the aftermath of 9/11and the invasion of Iraq with comparable feelings of doom). And the snowy, barren landscapes of (where else?) Los Alamos, New Mexico, provide the Americanized setting for Matt Reeves’ “Let Me In,” a remake of Tomas Alfredson‘s magnificent Swedish horror film, Let the Right One In” (2008).

I know, I thought the same thing: Why do we need a remake of “Let the Right One In,” when it was was done so right the first time? But then I started hearing incredibly good things. From Stephen King, who called it “the best American horror film in the last 20 years.” From John Ajvide Lindquist, author of the novel and screenplay for “Let the Right One In,” who wrote:

“Let The Right One In” is a great Swedish movie. “Let Me In” is a great American movie. There are notable similarities and the spirit of Tomas Alfredson is present. But “Let Me In” puts the emotional pressure in different places and stands firmly on its own legs. Like the Swedish movie it made me cry, but not at the same points. “Let Me In” is a dark and violent love story, a beautiful piece of cinema and a respectful rendering of my novel for which I am grateful. Again.

And from Kathleen Murphy at MSN Movies. From Roger Ebert. And then from Bilge Ebiri, who posted an interview with Matt Reeves his blog, mentioning that they’d talked about “why Ronald Reagan plays such an important role in his movie.” Well, that did it for me. Before I could read that, I had to go see the movie.

It seemed in advance like an inspired concept — to set the movie in a time when the President of the United States himself was an ancient, withered and unaging vampire, bleeding the middle class (“trickle down” indeed!) until it shriveled to a fraction of its previous size while letting federal spending and the national debt bloat to unprecedented grotesque proportions, greasing the gullets of voracious industrial fat cats with oily deregulation schemes, letting the filthy rich suck on the body politic… Oh, sorry. Got a little carried away with my golden memories there.

Anyway, it turns out that’s not what the movie is doing with the Reagan-era setting at all. As Reeves told Ebiri:

There’s an early chapter in the book that talks about the town where the story takes place, Blackeberg, which is where the author, John Lindqvist, grew up. It was a planned community, built over a few years, and it had no real history. And the book says, “They had no church, which is why they were so unprepared for what was to come.” Which is a great way to hook a reader! Now, the story takes place in the 1980s, and that made me think back to my own childhood. There’s an interesting parallel in the U.S. with that kind of planned community, in all of our suburban communities, and tract housing. We had our own version of that. In the 80s, it’s what we called Spielbergia. […]

The American version wouldn’t be a “godless” community. These were communities connected to faith. Especially at that time, in the Reagan era — right when Reagan was giving his Evil Empire speech. So, at that time, we thought of evil as something that was other – the Soviets — while Americans were fundamentally good. Now, imagine, what would it be like to be a 12-year-old in this world, a kid bullied so mercilessly that he gets these dark thoughts. Being in that community and having those kinds of feelings: Are you evil? In the book, he’s obsessed with serial killers. So I had to find a way to translate the essence of that story into this place that I remembered. At the same time, I knew I wanted to be really faithful to the story.

He is. As a horribly burned man is brought into the hospital at the beginning of the film, we see and hear Reagan on a TV in the reception area talking about evil at large: “We know that living in this world means dealing with what philosophers would call the phenomenology of evil or, as theologians would put it, the doctrine of sin.” Speaking to a gathering of the National Association of Evangelicals, Reagan denounces communism as “the focus of evil in the modern world” — which puts an decidedly American spin on this modern vampire tale.¹

The despondent, faceless mother of 12-year-old Owen (Kodi Smit-McPhee) — we never see her face — has given her life to Jesus and bottles of wine, at least since her separation or divorce from Owen’s father, who only appears as a voice on the phone, further accentuating the boy’s loneliness. The movie doesn’t say whether her religious devotion is normal or an expression of emotional problems, though Owen’s dad leans toward the latter view. Whatever the case, throughout the apartment, Jesus watches from the walls, aware of every sin.

Owen also watches. From his bedroom windows he looks down on the snowy courtyard and into the windows of inhabitants across the way, sometimes using a telescope to get a closer view. This “Rear Window” angle is also new to the American version, yet another way of reinforcing the characters’ chilly sense of isolation from one another. The wall between his room and Abby’s (Chloe Moretz), the one he hears strange sounds through and upon which he and his friend will tap Morse code messages, is a mural of a lunar landscape. It’s always night-time in Owen’s room.

(Spoilers to come.)

The film’s visual imagination is superb — though I think we could use just a few seconds less of the nightmarishly sped-up CGI during a few of Abby’s attacks. All we need is an impression, and the longer it goes on (even if it’s only a matter of seconds) the more the effect weakens and looks phony. But — and I never would have expected this from the director of “Cloverfield” (which used the gimmick of a consumer videocam to cut down on the visual effects budget) — the movie contains quite a few dazzlingly cinematic shots. A few of the most notable: the way the snow freezes in the air, caught by the strobing lights of emergency vehicles in the opening scene; a figure glimpsed from a distance in the light of a hospital window… who is revealed (in the same long shot) to be on the outside of the window (patterned after a shot in the first movie, but with subtle differences); an extended take, with the camera locked down in the rear interior of a car as it skids into a collision on an icy road…

One of the visual motifs of “Let Me In” mirrors its storytelling technique and the flawed vision of its characters, particularly Owen and the police detective (Elias Koteas). Like them, we can never quite see who is who, and where things are headed. Images are seen, mostly in the dark, through distorted lenses (peepholes, telescopes, mirrors, masks); through windshields and windows blurred by ice, snow and condensation; underwater or through eyes that have been physically damaged. Vision itself has been traumatized.

Some memorable scenes from the original movie are staged as mirror images, like the first appearance of the young vampire Abby on the jungle gym in the courtyard begins with Owen and his knife approaching the tree on the right instead of the left. Likewise, Owen and Abby are often seen as androgynous adolescent mirror images, living side-by side, each with one opposite-sexed “parent.” The movie plays with this pattern, and shows how behaviors are passed down through the generations (I’m reminded of the alcoholism, abuse and cancer inherited in David Cronenberg’s wintery masterpiece, “The Brood“), even more explicitly than the Swedish film.

Early in the film, we see Owen wearing a mask, brandishing a kitchen knife and approaching his own image in the mirror: “Are you a little girl… ?” — something he repeats with the tree and a pocket knife when he first encounters Abby. As in the first film, we don’t know what this signifies at first, but we find out that he’s mimicking the bullies who are picking on him at school and ritualistically acting out his revenge fantasies.

Abby, who has been 12 for a long time, is, in fact, a little girl — but she offers to help Owen because, as she says, she’s a lot stronger than he thinks she is. After he follows Abby’s advice and stands up for himself, hitting one of the bullies with a metal pole when he threatens to throw Owen into a hole in an iced-over pond, he is nearly expelled from school. But then there’s a scene that is dramatically different from the original, in which the most aggressive bully is, in turn, bullied with the same taunting language (calling him a “little girl”) by his older brother. This pattern culminates when, after the death of Abby’s “father” (Richard Jenkins), Owen sees a strip of photo booth pictures showing the two of them at roughly the same age. By the end of the film, Owen will fill that role in Abby’s life, a fate that is both horrifying and apt.

Which brings me back to Stephen King’s proclamation. The best American horror movie in the last 20 years? What’s the competition? “Let the Right One In” is from Sweden. “The Descent” is from New Zealand Great Britain. “Sean of the Dead” is British. “Memories of Murder” and “The Host” are South Korean. “Audition” and other “Asian Extreme” films have come from Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, China, etc. What have the great American horror films been since, say “Silence of the Lambs” (though I know that movie has its detractors)? I’d nominate “The Corporation,” but it’s Canadian. Perhaps “Ghosts of Abu Ghraiib” and “Standard Operating Procedure,” or “American Casino” or “When the Levees Broke”? What am I forgetting?

_ _ _ _

¹ A political footnote: George W. Bush also invoked “evil” in his address to the nation on September 11, 2001:

Good evening. Today, our fellow citizens, our way of life, our very freedom came under attack in a series of deliberate and deadly terrorist acts…. Thousands of lives were suddenly ended by evil, despicable acts of terror.

I believe that the use of this inherently religious terminology (in the context of 9/11) — something FDR did not feel the need to do in his ““date which will live in infamy” speech, asking Congress to declare war on Japan after the bombing of Pearl Harbor — was a tone-deaf mistake of the greatest magnitude. Bush was speaking not only to residents of the USA, but to the whole world, and his language failed to adequately take that into account. In that moment, Bush lost the “war against terrorism” even as he was declaring it. And every time he repeated it, he exponentially multiplied the original error until the world’s solidarity and support was shattered. No matter how often thereafter Bush would claim that he was not declaring war on Islam, the damage (reinforced by the administration’s self-undermining actions) was done, and would prove to be irreversible. A more powerful condemnation under the circumstances would have avoided applying the label to an act that was meant to be religiously polarizing. It only helped frame the conflict the way al Qaeda wanted it framed to begin with.

For a list of backgroud links and quotations regarding the above, see my annotated comment here.