A musical interlude

Dave Thomas and Catherine O’Hara do Steve and Eydie on the SCTV Solid Gold Telethon in 1978.

Dave Thomas and Catherine O’Hara do Steve and Eydie on the SCTV Solid Gold Telethon in 1978.

“I don’t think we need another film about the Holocaust, do we? It’s like, how many have there been? You know? We get it. It was grim. Move on. No, I’m doing it because I’ve noticed that if you do a film about the Holocaust, you’re guaranteed an Oscar…. ‘Schindler’s Bloody List,’ ‘Pianist’ — Oscars comin’ outta their ass.”

— Kate Winslet (in character) on “Extras” (2005)

There are two main reasons I don’t do Oscar predictions: 1) I’m bad at it; and 2) the Oscars take place in a corner of the cinematic universe that’s only tangentially related to the movies I love. The Oscar ceremonies have been called the Gay Super Bowl and that’s as good a characterization as any — or at least it was, until “Crash” won.

But some peculiarities at the Golden Globules got me to wondering about the Academy rules. Although I remembered that Peter Finch had won a posthumous Oscar for “Network” in 1976, I didn’t know for certain if the rules permitted a posthumous nomination — like, say, for Heath Ledger, who won a Globule for best supporting actor as the Joker in “The Dark Knight.” Turns out, nothing in the Academy’s Rule Six: Special Rules for the Acting Awards prohibits it.

Perhaps a more pertinent question would be: Is it really a supporting role? Kate Winslet got her hands on two Globules this year — one for lead performance in “Revolutionary Road” and another for supporting performance in “The Reader.” Some have suggested that the latter is a little like considering Faye Dunaway’s role in “Chinatown” a supporting one, but I figured the Hollywood Foreign Press Association just wanted to award Winslet a pair of Globulettes for reasons known best to themselves, so they went out of their way to nominate her in separate categories.

UPDATE: Indeed, Oscar voters have nominated Winslet’s “Reader” performance in the lead category. She did not receive a nomination for “Revolutionary Road” — even though she may well have received enough votes to qualify for both. At least, I think that’s what this rule says:

5. In the event that two achievements by an actor or actress receive sufficient votes to be nominated in the same category, only one shall be nominated using the preferential tabulation process and such other allied procedures as may be necessary to achieve that result.

[Oscar rules below.]

“I am you. Prepared to do anything. Prepared to burn. Prepared to do what ordinary people won’t do. You want me to shake hands with you in hell, I shall not disappoint you…. I may be on the side of the angels, but don’t think for one second that I am one of them.”

— Sherlock Holmes to Moriarty in “The Reichenbach Fall” (2012)

In a seething contemporary metropolis, a private citizen gifted with extraordinary crime-fighting abilities, and motivated by his own private demons, enters into an unofficial liaison with the police, who put up with his form of vigilantism because… well, because he cracks cases and catches crooks. He’s a great tabloid story, so the papers avidly display his distinctively costumed image on their front pages, building him up into a kind of superhuman figure. He fully trusts only one man, his live-in companion (no, not in that way!), frequent co-conspirator and closest advisor, who warns him that he may be getting too famous for his own good, becoming a target rather than a deterrent. He is ripe for a fall.

His city-wide celebrity attracts a nemesis, a criminal mastermind who is batshit crazy but also diabolically clever at complex planning. This villain is obsessed with his counterpart, whom he sees as an avenging “angel,” his mirror self and his only worthy rival. Determined to destroy his better half, he plans a series of daring schemes, assisted by scores of shadowy henchmen eager to do his bidding, to take his archenemy’s confidence and reputation down a few pegs.

I took this photo of my Cronenbergian incision Friday night after I had a biventricular ICD installed to help me with various arrhythmias I’ve had for years, and the congestive heart failure that flatlined me back in 2000. Now I am bionic. The image brings to mind so many movies (looks a little like a smiling third nipple in this particular shot — the swelling has since gone way down). But it reminds me most of the talking boil that sprouts on Richard E. Grant’s neck in Bruce Robinson’s insanely great “How To Get Ahead In Advertising” (1989), equally brilliant follow-up to the modern comedy classic “Withnail & I.” I’ll let you know if it starts bossing me around…

View image You see it or you don’t.

Toronto’s is an international film festival, and naturally the films are shot in locations all over the world. But one thing so many of the best films in this year’s fest have in common (a thing all great films have in common) is not the places in which they’re shot, or set, but the places they create, and pull you into. These aren’t travelogues. The films are the places, whether the geographical locations exist independently of the pictures or not.

There’s Texas and there’s Mexico and there’s “No Country for Old Men.”

Tommy Lee Jones’ character, Sheriff Ed Tom Bell begins Joel and Ethan Coen’s “No Country for Old Men” with an elegiac monologue about missing the “old times.” His words are spoken over a montage of western landscapes in blazing oranges and reds (the incomparable Roger Deakins is the DP). By the end of this reverie, we’re no longer in the past but in the harsh daylight of the present, and the color has drained from the images. The way Ed Tom sees it, he’s outmatched in the modern world where violence is random, unmotivated, and unpredictable.

Within moments we see a shocking example of what he’s talking about, as Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) strangles a man on the linoleum floor of an office, his dead yellow eyes fixed on the ceiling. That’s a terrifying touch: Chigurth doesn’t even look at his victim, even while he’s garroting the guy. And then, one of those Coen touches: a shot of the floor, covered with a mess of black heel marks from the killer and his prey.

“No Country for Old Men” is one of those movies I think provides a critical litmus test. You can quibble about it all you like, but if you don’t get the artistry at work then, I submit, you don’t get what movies are. Critics can disapprove of the unsettling shifts in tone in the Coens’ work, or their presumed attitude toward the characters, or their use of violence and humor — but those complaints are petty and irrelevant in the context of the movies themselves: the way, for example, an ominous black shadow creeps across a field toward the observer (“No Country” has a credit for “Weather Wrangler”); or a phone call from a hotel room that you can hear ringing in the earpiece and at the front desk, where you’re pretty sure something bad has happened but you don’t need to see it; or the offhand reveal of one major character’s fate from the POV of another just entering the scene; or… I could go on and on. To ignore such things in order to focus on something else says more about the critic’s values than it does about the movies. It’s like complaining that Bresson’s actors don’t emote enough, or that Ozu keeps his camera too low.

A moment here to celebrate the genius of one of the greatest talents in motion pictures, supervising sound editor Skip Lievsay, who has worked with the Coens (and Spike Lee and Martin Scorsese and others) since way back before the mosquito buzzing and peeling wallpaper of “Barton Fink.” Since the bug zapper in “Blood Simple,” in fact. Also, composer Carter Burwell (“Psycho III”!) has been associated with the Coens for just as long. He’s credited with the music in “No Country,” too, but it’s to his merit that I don’t even recall any music in the picture — except for one memorably Coen-esque appearance by a mariachi band.

When I read Cormac McCarthy’s novel, it struck me as a Coen screenplay just waiting to become a Coen film. Indeed, by that time it already was. And it could serve as a model of prose-to-film adaptation, choosing exactly the right moments and movements for the picture, and leaving alone others that are better suited to literature. (This is especially true of some very savvy omissions in the latter part of the movie.)

“No Country for Old Men” makes me want to echo Jean-Luc Godard’s famous celebration of Nicholas Ray: “Le cinéma est les Coens!”

Because I’m just really bad at it. I have no idea what these… people will do. I’ve never won an Oscar pool in my life. I try to enjoy the show, and I like analyzing the results, but I can’t pretend to divine the Academy’s will in advance. Who knows what they’ll do? Well, maybe you do.

The TV broadcast starts in about two hours. So if you want to make your predictions — or share your thoughts on the show while it’s in progress — please feel free to do so below. I’m going to be on deadline for the Chicago Sun-Times and RogerEbert.com, but I’ll check in whenever I can, mostly during commercials, to update comments.

The Muriels are back! Everyone’s favorite movie awards, the Muriels feature the longest presentation ceremonies of any other movie awards. They go on for weeks — from February 16 to March 6. Take that, Oscars! And there are no musical numbers or acceptance speeches, just pithy essays about the winners. Created by Paul Clark and Steve Carlson, and named after Paul’s guinea pig, the Muriels are now in their fifth year, and feature some categories that are even newer than before! (They are, in other words, new.)

So, in addition to Best Cinematic Moment, Best Cinematic Breakthrough and retrospective honors from 10, 25 and 50 years ago (plus, this year, a look at the best films of one of the best decades for movies ever, the 1950s), we have… Best Editing. Sure, the Academy has one of those, too (and they say a film can’t win Best Picture without an editing nomination), but you won’t find a better examination of why the winners deserve to win than this one by Muriel voter Michael Lieberman — which I feel compelled to quote in its three-paragraph entirety (no editing here!):

The one complaint I heard the most about Ebertfest this year is that it’s too much and too short. Is that a contradiction? Very well, Ebertfest contains contradictions. For now, I’m posting photos. Some concluding thoughts coming soon…

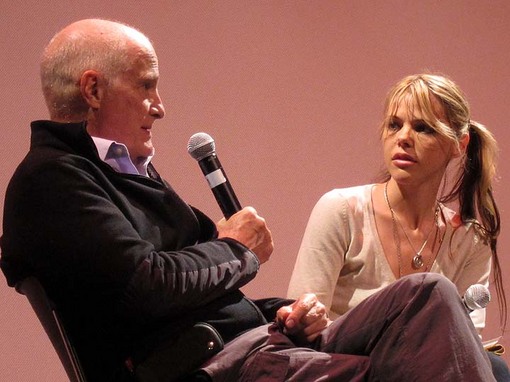

“Barfly” director Barbet Schroeder and Sunset Gun blogger Kim Morgan discuss Bukowski and Hollywood.

This is a very funny man.

A commentary on The Year in Comedy from Judd Apatow, the co-creator of “Freaks and Geeks,” “The 40-Year-Old Virgin” and… Seth Rogan:

It seems like comedy is more popular than ever right now. There have been many very successful comedies as of late: “Nacho Libre,” “Click,” “The Break-Up,” “You, Me and Dupree,” “Little Miss Sunshine,” “Babel.” But I think people always love comedies. I assume in the 1930s, people thought comedy was really popular because they had hit movies from the Three Stooges, the Marx Brothers, Abbott and Costello, and Laurel and Hardy. I think every decade has its huge comedies and comedy stars. We need comedy. Life can be brutal, and watching something funny with strangers in a large room somehow makes it a tiny bit more bearable.

When I saw “Borat” at the premiere, I was sitting near Eric Idle of Monty Python, one of the greatest comedy minds of all time. I said hello before the screening. I told him I made “The 40-Year-Old Virgin,” but he had not seen it. Still, he was very nice. While the film was playing, he would turn to me every so often during one of the more hilarious and outrageous moments, like the naked fight. His eyes lit up with joy and a facial expression that said, “Can you believe this?” It was as if he was so delighted by the movie that he needed to share it with someone, even if it was just some drooling fan that made a film he hadn’t seen.

(tip: MCN)

“Up in the Air” director Jason Reitman (known for his pie charts documented the whirlwind experience of his latest press tour in a movie (above) posted on Vimeo and /Film.

UPDATE: Reitman was nominated for a DGA award this morning, along with fellow directors Kathryn Bigelow, James Cameron, Lee Daniels and Quentin Tarantino.

The Formal Mr. Poland, aboard the 2006 Floating Film Festival. (Photo by Kim Robeson)

Happy “Birthday” to David Poland, whose Hot Blog, Hot Button column and Movie City News are favorite sources of information and commentary about The Biz around here. This week marks the Ninth anniversary of The Hot Button and the 1000th entry in The Hot Blog.

Check out the latest column to see how much has changed (and hasn’t) over these nine years. He’s also posted his Rules of Thumb — sort of a combination of the Ten Commandments for Understanding Showbiz and Charles Foster Kane’s “Declaration of Principles.” I think he’s dead right on all counts.

Congrats, David!

TOP TEN HOT BUTTON RULES OF THUMB

1. Great Media Outlets’ Standards Are Less Stringent When The Subject Is Entertainment And That Sucks.

2. $150 Million Is No Longer A Blockbuster In Theatrical… But Right Now Represents The Start Of A Road To More Than $200 Million In Returns to The Studio In Most Cases Thanks To The New DVD Market And Expanded International Theatrical Market.

3. Successful Movie Advertising Sells One Idea At A Time… And There Actually Has To Be An Idea Worth Selling

4. The Story Of The Moment Is Almost Never The Real Story

5. There Are Very Few Journalists In Entertainment Journalism

6. Talent Is Your Friend Until It’s Time For Talent Not To Be Your Friend

7. Reviewing Scripts Or Test Screenings Is Selfish And Immoral… You Do Not Know What Effect Sticking Your Nose Into Process Will Have And More Often Than Not It Is Negative

8. Opening Weekend Is Never About The Quality Of The Movie

9. There Are Things I Know And Things I Don’t Know And Sometimes They Change

10.Love What You Do And Do What You Love Or Get The F— Out.

I was going to ignore it, I really was. But several people have e-mailed me about the appearance of Armond White’s “Better-Than List 2008,” and requested an opportunity to discuss it here. Well, OK.

White insists once again that what “it all comes down to” is a contest between “movies you must experience versus movies that threaten to diminish you”:

Most of these high-profile films insult one’s intelligence, while the year’s best movies vanish from the marketplace for lack of critical support. This tragedy is exemplified by the scary acclaim for the year’s worst: The atrocious “Slumdog Millionaire” and Pixar’s hideous “Wall-E,” the buzz-kill movie of all time. Trust no critic who endorses them.

So, it’s not really Batman vs. the Joker. It’s “Transporter 3” BETTER THAN “The Dark Knight”: “Olivier Megaton, Jason Statham and Luc Besson reinvent the action movie as kinetic art, but impressionable teenagers mistook Chris Nolan’s nihilistic graphic novel for kool fun.”

I can’t tell from that sentence (which constitutes the entirety of White’s blurb-ument in this case) what the first part has to do with the second part, but it illustrates once again the meaninglessness of plugging movies into equations and pretending it’s criticism.

View image The light and the landscape.

View image Signs of man.

I was sheriff of this county when I was twenty-five. Hard to believe. Grandfather was a lawman. Father too. Me and him was sheriff at the same time, him in Plano and me here. I think he was pretty proud of that. I know I was.

Some of the old-time sheriffs never even wore a gun. A lot of folks find that hard to believe…. You can’t help but compare yourself against the old timers. Can’t help but wonder how they would’ve operated these times….

— Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones)

The land is black, swallowed in the shadows. The sky is beginning to glow orange and blue. This is Genesis, the primordial landscape of “No Country for Old Men.” We may think we’re looking at a sunset at first, but the next few shots show a progression: The sky lightens, the sun rises above the horizon to illuminate a vast Western expanse. No signs of humanity are evident. And then, a distant windmill — a mythic “Once Upon a Time in the West” kind of windmill. So, mankind figures into the geography after all. A barbed-wire fence cuts through a field. The camera, previously stationary, stirs to life, and pans (ostensibly down the length of the fence) to find a police car pulled over on the shoulder of a highway. There’s law out here, too.

View image Boundaries.

View image The law. (Do these images look sterile or “technical” to you?)

Light, land, man, boundaries, law. Each image builds subtly on the one(s) before it, adding incrementally to our picture of the territory we’re entering. The establishment of this location — a passing-through stretch of time and space, between where you’ve been and where you’re going, wherever that may be — seeps into your awareness. Not a moment is wasted, but the compositions have room to breathe, along with the modulations of Tommy Lee Jones’ voice, the noises in the air, and Carter Burwell’s music-as-sound-design. The movie intensifies and heightens your senses. Light is tangible, whether it’s sunlight or fluorescent. Blades of grass sing in the wind. Ceiling fans whir (not so literally or Symbolically as in “Apocalypse Now”). Milk bottles sweat in the heat. Ventilation ducts, air conditioners and deadbolt housings rumble, hiss and roar.

“To me, style is just the outside of content, and content the inside of style, like the outside and the inside of the human body—both go together, they can’t be separated.”

— Jean-Luc Godard”No Country for Old Men” has been called a “perfect” film by those who love it and those who were left cold by it. Joel and Ethan Coen have been praised and condemned for their expert “craftsmanship” and their “technical” skills — as if those skills had nothing to do with filmmaking style, or artistry; as if they existed apart from the movie itself. Oh, but the film is an example of “impeccable technique” — you know, for “formalists.” And the cinematography is “beautiful.” Heck, it’s even “gorgeous.” …

View image And the Exploding Head goes to… Seth Rogen and Paul Rudd in “Knocked Up”?

I’ll publish my annotated “best of” list next week, but while thinking back over the year’s movies I recalled some things that seemed to me “beyond category.” Or the usual categories, anyway. One way or another, they made my head feel that it might explode. So, while everybody’s preoccupied with all those other awards, here are the 2007 Exploding Heads for Achievement in Movies:

Best endings:

• “The Sopranos” (final episode): blackout

• “No Country for Old Men”: “Then I woke up.”

• “I’m Not There”: Dylan’s harmonica on “Mr. Tambourine Man”

• “Superbad”: Baby-steps toward adulthood, separating at the mall escalator

• “Zodiac”: Stare-down

Most electrifying moment:

A dog. A river. “No Country for Old Men.”

Best grandma:

“Persepolis”

Best surrogate grandpa:

Hal Holbrook, “Into the Wild”

“Arrested Development” Award for Best Throwaway Lines:

• “Keep it in the oven…” — Jason Bateman, “Juno”

• “… Terrorism…” — Michael Cera, “Superbad” (actually, Cera has so many astonishingly brilliant under-his-breath moments in “Superbad” and “Juno” it’s uncanny)

Best performance by an inanimate object:

(tie) The cloud (and its shadow), the candy wrapper, the blown lock housing in the motel room door, “No Country for Old Men”

Most cringe-worthy lines:

• “My cooperation with the Nazis is only symbolic.” — “Youth Without Youth”

• “That ain’t no Etch-a-Sketch. This is one doodle that can’t be undid, home skillet.” — “Juno” (the cutesy moment at the beginning when I nearly ran screaming for an exit; cutting this entire unnecessary scene would improve “Juno” immensely)

Funniest double-edged observation:

“He’s playing fetch… with my kids… he’s treating my kids like they’re dogs.” — Debbie (Leslie Mann) in “Knocked Up,” watching Ben (Seth Rogen) play with her daughter, who is loving it. That’s her point of view, and she’s right, but she says it like it’s a bad thing.

View image Ain’t nothin’ but the real thing, baby: Brian Dierker and Catherine Keener in “Into the Wild.”

The Real Thing:

“Non-actor” Brian Dierker, rubber tramp, “Into the Wild” (and, of course, his “old lady” Catherine Keener, actor extraordinaire)

Best film about the way The Industry really works since “The Big Picture”:

Jake Kasdan’s “The TV Set.” The moment I knew it was going to be exceptional (sharp, precise and, therefore, extraordinarily funny) was when the writer’s choice for the lead role gives an audition that’s just… underwhelming. He isn’t good. He isn’t terrible. He just isn’t enough. Which then allows the network execs to push for the “broader” alternative (“To me, the broad is the funny”). And even he proves himself capable of being not-awful — in rehearsal, at least…

Best political film:

(tie) “12:08 East of Bucharest” and “Persepolis” — a pair of smart, funny movies about the effects of political revolutions on individuals in (respectively) Romania and Iran.

Deadliest stare:

(tie) Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), “No Country for Old Men”; Briony Tallis (Saoirse Ronan), “Atonement”

Young comedy whippersnapper stars of the year:

Michael Cera (19), Ellen Page (20), Seth Rogen (25), Jonah Hill (24), Christopher Mintz-Plasse (18)

Game savers:

J.K. Simmons and Allison Janney, who come to the rescue of “Juno” not a moment too soon

Best torture porn:

The excruciatingly funny baptism scene with Paul Dano and Daniel Day Lewis (both of ’em overactin’ up a storm — but in a fun way), “There Will Be Blood”

Most worthless critical label:

“Independent.” A movie should not be viewed through its budget, financing or distribution. And in these days of studio “dependents” (Miramax, Focus Features, Paramount Vantage, Fox Searchlight, etc.), the term “indie” is frequently misleading at the very least.

Best bureaucrat:

Dr. Fischer (Alberta Watson), “Away From Her”

Best negotiations:

• Chigurh and the gas station owner, “No Country for Old Men”

• Chigurh and the trailer park lady, “No Country for Old Men”

• Chigurh and Carla Jean, “No Country for Old Men”

• “4 months, 3 weeks, 2 days”: The painfully protracted, ever-shifting moral balance (and exhausting power-struggle) in the hotel room, between the friend and the abortionist — while the pregnant woman herself passive-aggressively bows out of any responsibilities for what has happened, or will happen.

“Perfume” Award for Best Portrayal of Synesthesia:

“Ratatouille”

Best Supporting Crotch:

Sacha Baron Cohen, “Sweeney Todd.” An squirm-inducing scene-stealer that makes you long for a change of angle: Please give us an above-the-waist shot! (Did they have spandex in mid-19th century London?)

Traditionally (or, perhaps a better word is “statistically”), in order for film to win the Best Picture, it has to also receive director, screenplay, editing and acting nominations. Of the ten BP nominees this year, only “The Hurt Locker,” “Inglourious Basterds” and “Precious Based on the Novel Push by Sapphire” were nominated in all the winning categories.

Sure, there have been exceptions. James Cameron’s “Titanic” screenplay didn’t get nominated, either. And remember the stink when “Driving Miss Daisy” won Best Picture without even a nomination for its director, Bruce Beresford?

View image “Zabriskie Point” — an Antonioni movie on the cover of LOOK magazine in 1969: “Had he violated the Mann Act when he staged a nude love-in in a national park? Does the film show an “anti-American” bias? As a member of the movie Establishment, is he distorting the aims of the young people’s ‘revolution’?”

Watching Ingmar Bergman’s “Shame” (1968) over the weekend (which I was pleased to find that I had not seen before — after 20 or 30 years, I sometimes forget), I recalled something that happened around 1982. Through the University of Washington Cinema Studies program, we brought the now-famous (then not-so-) story structure guru Robert McKee to campus to conduct a weekend screenwriting seminar. McKee, played by Brian Cox in Spike Jonze’s and Charlie Kaufman’s “Adapation.” as the ultimate authority on how to write a salable screenplay, has probably been the single-most dominant influence in American screenwriting — “Hollywood” and “independent” — over the last two decades. Many would say “pernicious influence.” (Syd Field is another.)

It’s not necessarily McKee’s fault that so many aspiring screenwriters and studio development executives have chosen to emphasize a cogent, three-act structure over all other aspects of the script, including things like character, ideas, and even coherent narrative. Structure, after all, is supposed to be merely the backbone of storytelling, not the be-all, end-all of screenwriting. But people focus on the things that are easiest to fix, that make something feel like a movie, moving from beat to beat, even if the finished product is just a waste of time.

The film McKee chose to illustrate the principles of a well-structured story that time was Ingmar Bergman’s “The Virgin Spring.”

“Shame” is another reminder that Bergman’s movies weren’t solely aimed at “art” — they were made to appeal to an audience. Right up to its bleak ending, “Shame” is a rip-roaring story, with plenty of action, plot-twists, big emotional scenes for actors to play, gorgeously meticulous cinematography, explosive special effects and flat-out absurdist comedy. I don’t know how “arty” it seemed in 1968, but it plays almost like classical mainstream moviemaking today. (And remember: Downbeat, nihilistic or inconclusive finales were very fashionable and popular in mainstream cinema in the late 1960’s: “Bonnie and Clyde,” “Blow-Up,” “Easy Rider,” “Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry”…),

It’s important to remember that Bergman and his fellow Euro-titan Michelangelo Antonioni, who both died on the same day last week, were big-name commercial directors — who also helped moviegoers worldwide see the relatively young, originally low-brow, populist medium in a new light: as a (potential) art form. (The Beatles, who in 1964-’65 were the most popular youth phenomenon on the planet, even wanted Antonioni to direct their second feature, after “A Hard Day’s Night”!) And if they hadn’t been so popular and famous, they would not have been so influential. These guys won plenty of high-falutin’ awards at film festivals, but they were also nominated for Oscars in glitzy Hollywood.

View image”The Shining”: A bug under a microscope.

The most superficial and shopworn cliché about Stanley Kubrick is that he was a misanthrope. This is up there with calling Alfred Hitchcock “The Master of Suspense,” and leaving it at that. The cliché may contain a partial truth, but it’s not particularly enlightening. It’s just trite.

In the free Seattle weekly tabloid The Stranger, Charles Mudede writes about a local Kubrick series, and begins by stating: “Kubrick hated humans. This hate for his own kind is the ground upon which his cinema stands.” This is a nice grabber — particularly for readers who don’t know anything about Kubrick, or who want to feel the thrill of the forbidden when reading about him. (“Imagine! He hated humans!”)

Unfortunately for readers, this is Mudede’s thesis, and he’s sticking to it. Here’s his summary judgement of “2001: A Space Odyssey”:

As is made apparent by “2001: A Space Odyssey,” his contempt was deep.

It went from the elegant surface of our space-faring civilization down, down, down to the bottom of our natures, the muck and mud of our animal instincts, our ape bodies, our hair, guts, hunger, and grunts. No matter how far we go into the future, into space, toward the stars, we will never break with our first and violent world. Even the robots we create, our marvelous machines, are limited (and undone) by our human emotions, pressures, primitive drives. For Kubrick, we have never been modern.

OK, that’s one interpretation (though it gets the direction of the movement entirely wrong), but I think it’s a facile misreading of the film. Is there really something un-“modern” about portraying the raw, simple fact of evolution, with a little otherworldly nudge?

And why does Mudede have such contempt for apes and “animal instincts”? Is he going to apply “Meat is Murder” morality to primates? (Besides, they’re so dirty!) Or does he not feel the awesome and primal beauty in the whole “Dawn of Man” sequence? If he doesn’t, I suppose it’s no wonder he sees no wonder in the rest of the movie.

It wasn’t very far into “The Dark Knight” that the feeling first took hold of me: All this movie needs is a script and a director and it could be really, really great!

By the end I’d had a good time, and I already know I’d like to see it again. Maybe, I’ve been thinking, it’s kind of like a good album that’s been haphazardly sequenced, with a few lackluster (or even bad) songs and occasionally dumb lyrics, muddled arrangements, or klutzy production choices. But, you know, after a while you’re willing to overlook the parts that don’t work in order to enjoy the parts that do. At first exposure, those rough spots stick out and even hurt. Later on, you just accept them, get used to them, or even choose to ignore them.

Two and a half weeks into its theatrical release, is it still a sacrilege to believe, for any reason, that “The Dark Knight” is less than the greatest whatever ever? I sure hope not, because I wanted it to be great as much as anybody else. So, I front-loaded this post with my tempered impressions of “The Dark Knight” only to contrast them with the consensus opinion, which is, you might say, considerably more enthusiastic.

Ty Burr of The Boston Globe, one of our best newspaper critics in my opinion, wrote a provocative, nuanced piece about the response to “The Dark Knight” (“The ‘best movie of all time’? Who wants to know?”) in which he described being at a memorial service when “word got out among the teenagers and college kids that there was a movie critic present. One by one, they came up to me and asked the same question, with almost the same wording: Is “The Dark Knight” the best movie of all time?”

(Part 1 of these ruminations about “greatness” in art can be found here.)

View image What’re you lookin’ at?

Now playing, October 12 – 21 at The House Next Door: The Close-Up Blog-a-thon! House publisher Matt Zoller Seitz had this great idea:

Your piece could be as simple as a series of frame grabs with captions, or a blurb about a single close-up in a particular movie or television episode, past or current. Or it could be an essay about a certain performer’s mastery of (or failure to master) the close-up…. Or your piece could fixate on a director or cinematographer who is especially adept at pushing in to capture emotion. Or if you’re feeling contrarian, you could write about a memorable close-up that does not show a human face. Dealer’s choice all the way.So, I don’t know what I’m going to write about quite yet (probably more than one thing), but thinking about it today triggered a recollection of something Alfred Hitchcock had said about the impact and intimacy of close-ups, and how they should not be used indiscriminately. They are the bazookas in a filmmaker’s arsenal. (“Amongst our weaponry are such diverse elements as… close-ups!”)

View image Kindly old man or dirty old man? Or both?

Hitchcock also liked to talk about how context gave meaning to close-ups, a compositional and editorial principle he liked to cite as an illustration of “pure cinematics” (but which also goes by the less exalted name of “montage,” a basic element of film grammar). He told Francois Truffaut (in the interviews collected and printed in “Hitchcock/Truffaut” — or is it “Truffaut/Hitchcock”?): “”Let’s take a close-up of [“Rear Window” star James] Stewart looking out of the window at a little dog that’s being lowered in a basket. Back to Stewart, who has a kindly smile. But if in the place of the little dog you show a half-naked girl exercising in front of her open window, and you go back to a smiling Stewart again, this time he’s seen as a dirty old man!”

Here’s a clip of Hitch explaining it all for you — and playing the lead role in a custom-made example:

What he’s describing is, of course, the famous Kuleshov effect, which… oh, let Mr. Wiki provide the details:

View image The Kuleshov effect in six shots. Or four.

The Kuleshov Effect is a montage effect demonstrated by Russian filmmaker Lev Kuleshov in about 1918.

Kuleshov edited a short film in which shots of the face of Ivan Mozzhukhin (a Tsarist matinee idol) are alternated with various other shots (a plate of soup, a girl, an old woman’s coffin). The film was shown to an audience who believed that the expression on Mozzhukhin’s face was different each time he appeared, depending on whether he was “looking at” the plate of soup, the girl, or the coffin, showing an expression of hunger, desire or grief respectively. Actually the footage of Mozzhukhin was identical, and rather expressionless, every time it appeared. Vsevolod Pudovkin (who later claimed to have been the co-creator of the experiment) described in 1929 how the audience “raved about the acting…. the heavy pensiveness of his mood over the forgotten soup, were touched and moved by the deep sorrow with which he looked on the dead woman, and admired the light, happy smile with which he surveyed the girl at play. But we knew that in all three cases the face was exactly the same.”

So, there you go. Get closer. Check out the Close-Up Blog-a-thon and submit your own ideas. I’ve got to focus in on mine…

Chicago music critics and “Sound Opinions” radio co-hosts Jim DeRogatis and Greg Kot are hosting an evening devoted to their “best rock movies of all time” Friday at the Pabst Theater in Milwaukee. They’re not saying yet what those will be (besides, let’s face it, “This Is Spinal Tap” and “Stop Making Sense” and “The Girl Can’t Help It” and…). But DeRogatis was happy to eliminate some of the usual suspects in advance during an interview with the Onion A.V. Club Milwaukee. A few choice comments:

On “The Last Waltz” (Martin Scorsese, 1978): “I’m from the punk era. I believe what’s great about rock ‘n’ roll is community and the tearing down of boundaries. And the basic thrust of ‘The Last Waltz’ is that these are superheroes so much better than you..”

On “U2: Rattle and Hum” (Phil Joanou, 1988): “I’m not saying it’s dishonest. It absolutely shows what they are. They are big, superstar rock stars full of pretension. But for the same reason I have no desire to sit through ‘Saw VII’–because torture porn makes my stomach hurt–so does ‘Rattle & Hum.’ [Laughs.] U2 are assholes, the movie shows them as assholes, but that doesn’t make it any fun to watch.”