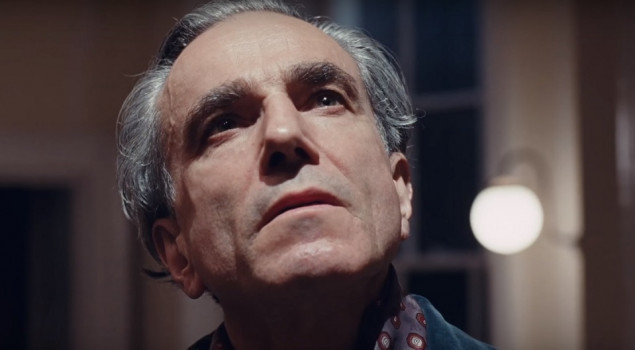

If he can help it, Reynolds Woodcock (Daniel Day-Lewis) barely looks at people. The master dressmaker at the center of Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Phantom Thread” is too busy to avert his gaze from his work, and the interruption can’t possibly be as important. Where other films might feel the need to announce or explain Woodcock’s (not unearned) high opinion of his dresses, “Phantom Thread” needs only to show how Woodcock comports himself to indicate his view of himself as a grand artist is as important to him as the actual work. This gives his later stares, be they inviting or chilling, a greater significance. The way Day-Lewis directs his eyes in “Phantom Thread” shows the journey of a man whose self-identity shifts over the course of the film, and whose enigmatic, controlled exterior belies volatile emotions.

Day-Lewis’ casting, then, is essential, both for his ability to make the kind of hairpin turns required and for the mysterious aura around him. Few actors of the modern era have managed to keep the kind of mystique that Day-Lewis has. Part of it stems from the relatively infrequent pace he keeps as a performer, having starred in only seven films in the last 20 years. Part of it is due to the record three Best Actor Oscars he’s picked up (“My Left Foot,” “There Will Be Blood,” “Lincoln”) despite a slim filmography of less than 20 major works. And part of it comes from from the intensity of his work process, which often sees him going through rigorous preparation and staying in character throughout filming.

Other actors have attempted their own version of this form of immersive acting (frequently identified as the Method, though it’s not actually Method’s defining characteristic), but their antics usually draw attention to themselves as being little more than self-important, cast-aggravating stunts (see: Jared Leto). Day-Lewis’ work, on the other hand, is genuinely emotionally expressive and shows an actor who’s deeply internalized characters’ being, making even his most floridly theatrical creations feel immediate and lived-in. Reynolds Woodcock is his latest invention, and potentially his last. Day-Lewis has said he plans to retire from acting, and while he’s certainly taken breaks before (see: the five-year stretch between “The Boxer” and “Gangs of New York” or the same length between “Lincoln” and this), his interviews suggest that, at least for the time being, he means it. If it is indeed his final work, it’s a fitting one that’s in keeping with the actor’s career of telling stories of grand, often larger-than-life men whose self-identity clashes with, and often destroys, their relationships.

Following an early appearance as a vandal in John Schlesinger’s “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” Day-Lewis’ acting career properly began on stage and in British television productions, playing Romeo and Flute in “Romeo and Juliet” and “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” respectively. His first few film roles, as a hooligan who harasses Ben Kingsley in “Gandhi” and as Captain Bligh’s (Anthony Hopkins) loyal right-hand man, John Fryer, in “The Bounty,” don’t really signal that Day-Lewis was about to become one of the most acclaimed actors of his generation. If anything, he seems a bit over-rehearsed in the latter especially, taking on an affected, prim tone and diction that fits the character but always feels a bit stilted. His talent and intensity is clear, but he seems too eager to impress.

That weakness totally disappears in his breakthrough role as closeted skinhead Johnny in Stephen Frears’ “My Beautiful Laundrette.” The film sees his character reconnecting with Omar (Gordon Warnecke), a British-Pakistani friend with whom he had a romantic relationship as a boy. In their first scene together, Day-Lewis projects an affected indifference, looking off to the side and the distance and nodding slightly but dismissively at Omar … until his old friend mentions his mother dying and something shifts in Day-Lewis’ eyes. Many of his early scenes in the film show him attempting to look disinterested in Omar and his new business. The film doesn’t spell it out, but Day-Lewis’ choices suggest a man who’s adopted an intolerant persona so as to get away from his fear of his sexuality. It’s later, as he and Omar draw closer together, that he seems more natural and at ease, more inclined to smile and look characters directly in the eye (and, it must be said, to show real affection toward Omar, as in one scene where he playfully licks him). More telling still are his scenes where he’s reminded of the pain his fascist role-playing caused for people he cared about, lowering his head in shame. His choice of a false identity wrecked his relationships for years; it’s his choice of a real one that saves them, and him.

That same year saw Day-Lewis taking on another character who assumes an outsized and false persona in James Ivory’s “A Room with a View.” As the hilariously pompous Cecil Vyse, fiancé to Helena Bonham Carter’s Lucy, Day-Lewis’ every gesture and over-enunciation (“I be-lieve in democracy”) is calculated to communicate his character’s deep and abiding belief that he is smart (he isn’t) and an important member of society (definitely not). Introduced flinging a doorway open and speaking “she has accepted me” in Italian (before having to translate to a clearly annoyed audience), he moves and stands in a way that’s somehow both flowing and rigid. Everything about Cecil is for show, whether he tries to take Lucy’s arm in public or he’s standing in the background reading a book entirely to show off that he’s reading (signified by the odd way he crooks his head). Cecil is only himself when privately and ineptly attempting to woo Lucy, in which his mock-confident stance falls and he shows a more nervous, halting manner, with his abortive kiss of Lucy serving as his most human moment in the film. It’s in these small moments that Cecil, effectively a foolish figure in most of his scenes, becomes sympathetic, as Day-Lewis shows a deeply insecure man who’s chosen to project his own sense of self-importance in order to hide and, hopefully, become the respected figure he believes he should be.

Around this point in time, Day-Lewis started getting larger roles and greater opportunities to challenge himself. His first run at being a leading man in Philip Kaufman’s “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” saw him first diving into his intense preparation methods by learning Czech. Like his two previous prominent roles, it also saw him playing with identity, this time as it relates to both personal relationships and professional status. As the womanizing doctor Tomas, Day-Lewis plays someone who’s completely removed romantic affection from sex, one who fancies himself less a Casanova than a Cartier, a sort of sexual explorer. Day-Lewis brings a sort of thoughtful dispassion to the role, coming onto Tereza (Juliette Binoche) with confident casualness—he prompts her to take off her clothes while chewing an apple, as if he were making a matter-of-fact observation. When Tereza begins a nervous sneezing fit, Day-Lewis plays his medical examination-cum-seduction clinically, going through his routine impassively enough that the implied intimacy pushes her to make the first real move.

His detachment falls away, however, when he’s forced to reconcile his desire to continue his casual affairs with his love for Tereza. This parallels his desire to continue practicing medicine with his refusal to take back criticisms of the new communist regime. Day-Lewis’ natural intensity in later performances would be more explosive, but what’s impressive here is how he plays his inner conflict more implosively, his jaw clenched and eyes cast downward when reuniting with Tereza or taking in a bureaucrat’s demand that he renounce his previous criticisms. He’s attached himself to a self-conception as a great lover that conflicts with his true love, while a mirror image of this conflict happens in his professional life, where he’s defined himself as a doctor but can’t bring himself to renounce his ideals in order to keep practicing. It’s only by removing himself completely from all possibility of conflict that he’s able to find peace with Tereza, before the film reaches its heartbreaking ironic end.

Between his roles as a gay skinhead, a buffoonish dandy and a lover-turned-true romantic, it seemed Day-Lewis was capable of nearly everything. This was quickly disproved with 1988’s “Stars & Bars” and 1989’s “Eversmile, New Jersey,” both barely remembered comedies. The former sees him as a British art expert forced to travel to the Deep South to purchase a rare Renoir painting from a group of Flannery O’Connor rejects; the latter sees him as a traveling Irish dentist (!) and goes on a series of surreal journeys in Argentina (!!!) while offering free services from a “dental consciousness” foundation (???). “Stars & Bars’” conflicts between Day-Lewis’ effete Englishman and the stereotypical southern gargoyles he encounters are so broadly drawn that it likely would have been rancid regardless of who had been cast, but Day-Lewis is singularly ill-equipped for the role, reacting to all of the crazy goings-on around him with a mannered, mugging bewilderment and irritation that mostly just suggests his discomfort in the role. It’s the rare film where one sees Day-Lewis and thinks, “Hugh Grant really would’ve been a better fit here.” He’s slightly less self-conscious in “Eversmile,” but his speech pattern is weirdly unnatural, his actorly angry outbursts out-of-character with the affable hero we’re introduced to. One admires his willingness to try anything, but neither film gives him much to hang onto amid all the craziness, and he makes for a poor straight man as a result. He hasn’t attempted a comedy since (pity—he’s hilarious in “A Room with a View”).

His move away from “rising star” territory to “all-timer” status was cemented with 1989’s “My Left Foot,” his Oscar-winning portrayal of Irish artist Christy Brown’s daily frustrations as he attempts to make art, communicate with others and find love as he lives with cerebral palsy. Much has been made about Day-Lewis’ in-character behavior behind the scenes, which ranged from understandable (learning to paint and write with his foot, Christy’s only functional limb) to extreme (forcing crew members to wheel him around and spoon-feed him). Day-Lewis’ physical commitment is laudable and genuinely impressive, as much for the intense concentration he summons in his face for every action as the actual effort required to do it. What lifts his work out of typical stunt-acting territory, however, is the emotional expressiveness Day-Lewis gives Christy.

He likely won the Oscar for a mid-film scene at a restaurant after his first successful gallery showing, in which he first showcases Christy’s raucous sense of humor, then learns that his speech teacher (Fiona Shaw) doesn’t share his romantic feelings. Day-Lewis’ face slowly contorts before jerking wildly, attempting to make the situation as uncomfortable for everyone around him as possible as he spits out a furious congratulations to Shaw’s engagement. The way Day-Lewis’ eyes and voice fume and burn a hole through Shaw keeps the scene away from the simplistic, condescending pity a lesser film might attempt; by allowing that Christy could be both understandably lovelorn and petty at the same time, he shows him as someone who wishes to be seen as someone with a unique voice, one that needn’t always be pleasant.

It was three years before Day-Lewis would appear in another film, having collapsed onstage during “Hamlet” after claiming to have seen the ghost of his father (poet Cecil Day-Lewis); what seemed like an atypically long break for an Oscar-winner became a harbinger of things to come, but that absence also informs his work in Michael Mann’s “The Last of the Mohicans.” As Nathaniel “Hawkeye” Poe, the adopted white son of Chingachgook (Lakota activist Russell Means), Day-Lewis has an air of quiet mystery around him, having come from one world and wholly adopted another. He’s taciturn in the classic action star sense, but there’s a greater thoughtfulness to him, with the actor speaking in a steely-eyed matter-of-factness in moments of action and a more poetic, spiritual tone when bonding with Madeleine Stowe’s Cora. He’s a perfect Michael Mann hero, in other words—a master at what he does with a hidden romantic side, and Day-Lewis’ the quietness of Day-Lewis’ performance makes his few stirring speeches (his offered self-sacrifice, the famous “I will find you” to Cora in front of the waterfall) all the more potent because Day-Lewis’ face and neck seem to be summoning up all of the energy he’s kept conserved in his body throughout the rest of the film. And yet, this hidden passion has a sad sense of futility, less in Day-Lewis’ actions than of his being the white son of a Mohican man. The happiness of Hawkeye and Cora’s reunion is real, but Mann uses this as a poignant counterpoint to a greater story, one of the loss of an entire people.

Day-Lewis gets more stirring speeches in his reunion with “My Left Foot” director Jim Sheridan, 1993’s “In the Name of the Father.” Sheridan’s film, covering the wrongful incarceration of Irish citizens by the British government looking for IRA bombing scapegoats, hasn’t aged particularly well, with Sheridan and screenwriter Terry George’s displaying much of the dull righteousness that plagues George’s own films (“Hotel Rwanda,” “Reservation Road”). Day-Lewis vividly portrays anguish in his torture scenes and radiates a forthright resolve when fighting to clear his name later in the film, but “In the Name of the Father” is most effective when dealing with the difficult relationship between Day-Lewis’ Gerry Conlon and his father Giuseppe (Pete Postlethwaite). One gets the sense that fuck-up Gerry, with his stringy hair and fidgety goofiness, is the closest Day-Lewis came to playing a younger version of himself on screen, with the actor showing great comfort and lack of self-consciousness when he’s simply palling around with his friends. He’s more self-conscious (purposely so), when around his father, with the younger actor adopting a hunched walk and downward gaze that suggests someone who’s both weary of his father’s critical nature and genuinely cognizant of the truth of his criticisms. It’s telling that Day-Lewis’ pain during the torture scenes is clearest not when he’s being physically assaulted, but when his tormentors threaten to murder his father, his face growing twisted, his eyes bulged.

The best scene in the film sees Day-Lewis bringing a wiry, nervous energy, as he finally tells off his dad for constantly getting on his back, bobbing around, gesticulating wildly, expelling all of the pent-up frustration he’s kept from his father. “That’s when I started to rob, to prove that I was no good.” And yet, by the end of the scene, it’s his father’s embrace that’s able to calm him. Day-Lewis’ journey is moving, in spite of the film, because we see someone who’s defined himself solely by attempting to get away from his father gradually embrace his family, as much to prove to himself as to his departed dad that he is, in fact, good. It’s also this journey that elevates “In the Name of the Father” slightly above Day-Lewis and Sheridan’s third film, 1997’s “The Boxer,” which, despite the actor’s convincing physical transformation as a boxer, doesn’t give the actor much to play outside of fatigued decency.

Day-Lewis earned his second Oscar nomination for “In the Name of the Father.” He’s even better, however, that same year in Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece “The Age of Innocence,” the most moving film he’s appeared in. The normally demonstrative actor plays Newland Archer as someone who’s spent his whole life bottling up his emotions, suggesting a man of roiling pain and yearning beneath a calm exterior. Joanne Woodward’s narrator notes that Archer privately questions the strict New York societal rules and mores without publicly challenging them, and true enough, Day-Lewis wears a mask of polite neutrality, brightening up only when Michelle Pfeiffer’s Ellen Olenska, the cousin of his fiancée May (Winona Ryder), is around. Watch his easy, joking nature when he and Ellen mock Richard E. Grants’ Larry Lefferts and compare it with any scene in which he’s paired with May, to whom he shows a polite but detached charm, as if he’s negotiating how much affection he has to show her. Day-Lewis builds his performance on the banked frustration that manifests itself in Newland’s body, in glances and gestures held slightly too long (his kiss on Ellen’s hand after convincing her to give up divorce), in the tortured, wavering tone his voice takes in the few moments he articulates his love for Ellen. His inability to break out of his role as a member of polite society, of the restrictions he privately despises, makes his final scene all the more heartbreaking, with Day-Lewis trusting his stillness to communicate the absolute paralysis Newland feels, someone doomed to an identity he never wanted but was never able to shake.

1996’s adaptation of “The Crucible” is now perhaps more notable as the film where Day-Lewis met his wife (and future collaborator) Rebecca Miller, daughter of playwright Arthur Miller. The film did poor business and was viewed with mild disappointment at the time, but it’s a worthy addition to the actor’s body of work. Day-Lewis’ John Proctor is uncharacteristically but deliberately sedate for much of the film, suggesting a character who’s less practiced in bottling up his emotions than Newland Archer and someone who’s projecting a sense of being the sole voice of calm and reason in a frenzied arena. He seems to desperately avoid stirring any emotion in himself, avoiding Abigail (Ryder) gaze when she brings up their passion together. It’s a slow-burning performance, with the actor gradually allowing Proctor’s shame to register more visibly on his face, his fury disappearing from his eyes as he confesses his own part in the affair, the breath he lets out at the end of his plea that of a man accepting his status as a sinner, if only it will save his wife. It’s this slow-burning quality that makes his shouted “because it is my name” in the finale so satisfyingly cathartic. Day-Lewis’ strained shouts, his pleading, shaking body show a man who’s resolved to find some victory, however pyrrhic, to cement himself as one of the few who did not give himself over to a plague of hysteria and hatred, as well as someone who can finally look his wife in the eye with love rather than shame.

After the twin relative disappointments of “The Crucible” and “The Boxer,” Day-Lewis disappeared from the screen for five years, taking up cobbling in Florence and starting a family with Miller while turning down roles ranging from Aragorn in “The Lord of the Rings” to the Fiennes’ brothers roles in “The English Patient” and “Shakespeare in Love.” His absence makes his return with Martin Scorsese’s flawed but fascinating 2002 epic “Gangs of New York” all the more mythic, with Day-Lewis’ Bill “The Butcher” Cutting introduced like a giant, his boots stepping like a bull, his handlebar mustache and American Eagle-emblazoned glass eye making an immediately imposing impression. Speaking with an approximated early New Yorker cadence and flat vowel sounds that somehow suggest a middle ground between roughneck and rococo, he’s a fearsome character, spitting hatred toward immigrants with both relish and genuine fury. Where some Day-Lewis characters avoid others’ gaze for a variety of reasons (fear, shame, contempt), Bill’s whole being has been built on his staring holes through people, assessing their weaknesses, strengths, and whether they’ve the courage to meet him head-on.

That’s also the center of the film’s best scene, in which an American-flag draped Bill gives Amsterdam (Leonardo DiCaprio, not quite up to task for Scorsese yet) a bedside lesson. Earlier scenes of Bill strutting confidently through New York streets or howling in violent rage at a would-be assassin showcase Day-Lewis’ capacity for unfettered emotionalism, with the actor showing no weakness and no bounds (not even bullets in his shoulders) that can keep him from espousing both his nativist worldview and his belief that he fully embodies what America should be. Yet Bill admits to a weakness he’s shown in the past, and the self-mutilation it took to kill it in himself. His heavy breathing as he describes being forced to live in shame, along with the alternating faraway look and stare through Amsterdam, shows how Bill’s defined himself as much by his need for an enemy as his sincere pride in his heritage and hatred for others.

Day-Lewis’ increasingly infrequent output and towering, theatrical performances have made most of his post-90s films major events, but 2005’s “The Ballad of Jack and Rose,” written and directed by his wife, Rebecca Miller, mostly slipped under the radar. It’s a gem of a film, like a non-insufferable version of “Captain Fantastic” that actually dives into the troubling implications of self-isolation and absolute adherence to ideals. As Jack, an dying ex-hippie and environmentalist living in isolation with a daughter (Camilla Belle) who’s developed a secret, incestuous love for him, Day-Lewis exudes both a gentleness and a sense of loss, speaking of a former commune with a wistfulness that suggests someone who never really gave up the dream of the ‘60s even as he watched it die. There’s a devilish joy in his face when he first meets Beau Bridges’ yuppie land developer and readily admits to shooting up his housing development, but that’s complicated as he learns of Rose’s true feelings for him. His climactic confrontation with Bridges, in which he agrees to sell his land, sees him confronting how hewing so closely to that ’60s dream, embodying it, has doomed his daughter. His breakdown is peppered with rueful laughter amid tears of defeat, a recognition of the absurdity of defining one’s self by one idea, one he admits he can’t fully remember what it was about beyond “something different.”

“The Ballad of Jack and Rose” is a minor but worthy addition to Day-Lewis’ filmography. His next project, Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2007 epic “There Will Be Blood,” is a giant, both in his personal body of work and in modern film history. Hailed by many as one of the defining films of the 21st century, it also provides him his greatest role as Daniel Plainview, the self-made oil man turned monster. The performance is remembered as being volcanic, deliriously bigger-than-life, even deliciously over-the-top. In truth, it’s not a loud performance for much of the first two-thirds, even as Day-Lewis turns over Anderson’s florid dialogue in his mouth with a plummy, John Huston-influenced accent. Perhaps that’s understandable, however, given that even before his explosions, Plainview burns with barely repressed rage and hatred for everyone around him even when he’s at his quietest.

Day-Lewis and Anderson understand Plainview as the embodiment of American capitalism. Appropriately, Day-Lewis’ approach to almost every conversation is transactional. The actor’s face shows disbelief whenever he’s encountered with someone whose primary objective isn’t getting money (as when old man William Bandy attempts to bring him to church) and measured impatience whenever someone doesn’t get to the point of exactly what they want as soon as they start a conversation with him (“just answer me directly,” he says at one point when trying to figure out whether his “brother” wants to stay with him). This is at its most apparent when he and Eli (Paul Dano) butt heads, with Day-Lewis leaning in with irritation, his face practically clenching as he tries to summon all of his anger into his voice rather than just slapping the weaselly little shit in front of him (though it’s enormously satisfying when he does).

The film’s conclusion sees him flipping this around, with Plainview’s uncharacteristically slack body language (hunched, turned away from Eli) giving his enemy a false sense of confidence before he can casually tear his hope of redemption away. As with “The Crucible,” Day-Lewis’ big explosion—this time into outright stark-raving, animalistic rage, drooling and towering over Eli while pushing at him to tease him—wouldn’t count for much if not for the slow-burn of the rest of the performance, with the actor’s gradual shift from at least somewhat human to All-Powerful American Businessman as a Monster shown by his body going from upright to crooked, his face from quietly hateful to anything but.

And yet, there is something human in Plainview before he rips it out trying to become The American Businessman. In his early scenes with son H.W. (Dillon Freasier), he’s more easygoing, even playful with him, showing real affection that goes beyond wanting his legacy to last and into real love. He’s also warmer and more prone to joking when he believes he’s found his brother (his only tears in the film come when he learns of his real brother’s death). His confession at Eli’s church is so memorable because Day-Lewis, in close-up, signifies his total disinterest, even mocking attitude, toward Eli for every accusation outside of abandoning his child. The way Day-Lewis attempts to get back to the going-through-the-motions tone after first admitting to his truest sin is one of his best, unremarked-upon moments in the film, with his head-shake and self-collecting grimace showing someone who believes he may have gotten through the worst of it before Eli brings it up again and he’s forced to spit it out, then exclaim it to the world. The “my boy” seems to die in his breath, his guilt tearing at him for once … until Eli gives him an easy out, bringing his attention back to the absurdity of the baptismal performance. “I’m a family man,” he intones early on, and the tragedy in “There Will Be Blood” is watching Day-Lewis go from exploiting that and truly believing it to totally cutting himself off.

“There Will Be Blood,” along with Day-Lewis’ second Oscar win, cemented his status as the World’s Greatest Actor in the eyes of many, giving the sense that he could do anything. Rob Marshall’s 2009 disaster “Nine,” based on the musical adaptation of Federico Fellini’s “8 ½,” seems to exist to remind everyone that even Day-Lewis is human. In truth, his singing voice, though strained whenever he hits his highest register, is fine, if not nearly robust enough to handle musical theater. The bigger problem in the musical sequences is that Marshall cuts around him (whether it’s to a different scene or an angle that doesn’t match the previous one), undercutting his work and rendering his physicality essentially impotent. The rest of Day-Lewis’ performance is too one-note (that note being “self-consciously glum and exhausted”), particularly compared with the seemingly effortless greatness of Marcello Mastroianni in Fellini’s film. It’s not his worst performance, but it may be the worst use of him, as he never seems to get the chance to dig into it.

He’s on surer footing in Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln,” which earned him his record third Best Actor Oscar (beating out formidable competition from fellow Anderson muse Joaquin Phoenix in “The Master”). The first thing one notices is his soft, reedy voice, a more historically accurate than the sonorous one he’s frequently imagined to have (and that original star Liam Neeson would have brought). Day-Lewis’ folksy vocal choices—the relaxed pace, the self-deprecating tone—make the character of Lincoln seem more human and approachable, even as his mythic figure and ability to hold a room showcase what made him a legend in his time. That contradictory nature comes through in every scene in which Lincoln both makes a point (usually about slavery) and breaks the tension with a story, with Day-Lewis varying the rhythm and volume of his speech and timing every gesture to carry everyone in the room along with him at the same time. More impressive still is how Day-Lewis instills Lincoln with the sense of having the weight of the present and the possible future on him, his back crooked, his face fatigued. If “Lincoln” the film is a portrait of the difficult process of moving the needle forward even slightly, Lincoln the performance is about how historic figures attempt to wrestle with the possibility that their every action and failure will have consequences that affect generations of people.

“Phantom Thread,” Day-Lewis’ first film in five years, is yet another movie that deals extensively with a larger-than-life figure’s conception of themselves and how that affects their personal relationships. Reynolds Woodcock has a tendency to look inward or downward, and when he does look at others, it’s usually a withering stare over the top of his glasses, a dismissive expression communicating that whatever or whoever he’s looking at is beneath him (something further underlined by his lilting, regal voice). He’s someone whose status as a great artist has allowed him to have total control over his life and surroundings, with everything flowing with grace and ease around him; it’s ironic, then, that Alma (Vicky Krieps) catches his eye by being out of place and uncertain in her movements, causing him to beam warmly in a way that gives a totally different energy than his polite smiles toward his clients. This belies his belief that Alma can be formed and totally controlled by him; his hands move fastidiously when he’s measuring her for a dress, a seduction technique that carries an air of possessiveness.

The film details the battle between the two for control over their relationship. The way the warmth drains from Day-Lewis’ face when he’s surprised by Alma one night is as painful as any of Daniel Plainview’s pronouncements that his son is a “bastard from a basket,” to say nothing of his exaggerated, contemptuous movements and petulant expression when he deigns to eat something that Alma prepares differently than he’s used to. The less said about “Phantom Thread’”s conclusion at this point in its release, the better, but Woodcock’s humbling as a partner in their relationship is stunning in its metaphorical power. Relationships are kept alive and on equal footing by partners allowing themselves to be weak and vulnerable in front of the other; Day-Lewis’ mock-naïve movements and goading expression upon realizing he’s been forced to do so suggest that this is something that he’s only just found out he always wanted. In his professional life, he identifies as the master of his work, even as he fears it may be obsolete; in his personal life, he finds he prefers to be the willing pawn. It’s perhaps not the healthiest relationship, but after a career of playing characters struggling to stick to their self-ascribed roles, there’s something strangely moving about Day-Lewis closing his career playing someone who finds the thrill of letting go.