“The Boxer” is the latest of Jim Sheridan’s six rich stories about Ireland, and in some ways the most unusual. Although it seems to borrow the pattern of the traditional boxing movie, the boxer here is not the usual self-destructive character, but the center of maturity and balance in a community in turmoil. And although the film’s lovers are star-crossed, they are not blind; they’re too old and scarred to throw all caution to the wind.

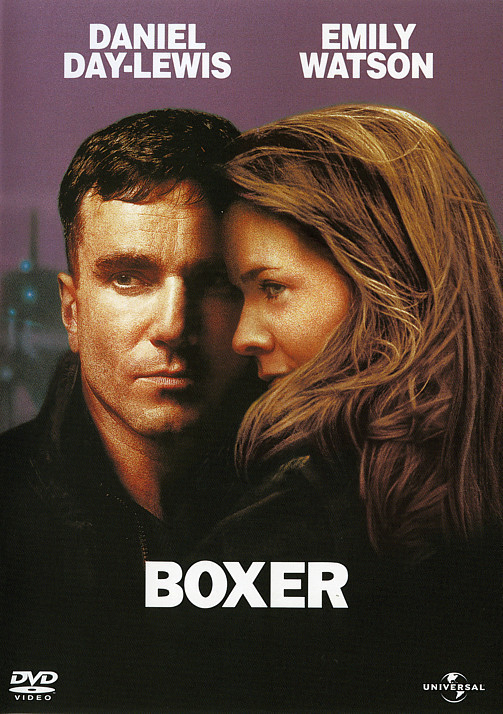

The film takes place in a Belfast hungering for peace. It stars Daniel Day-Lewis (also the star of Sheridan’s “My Left Foot” and “In the Name of the Father”) as Danny Flynn, an IRA member who was a promising boxer until he was imprisoned at 18 for terrorist associations. Refusing to name his fellow IRA men, he was held captive for 14 years, and is now back on the streets in a city where Joe Hamill (Brian Cox), the ranking IRA man, is trying to negotiate a truce with the British.

Danny was in love as a young man with Maggie (Emily Watson), Hamill’s daughter. After his imprisonment, she married another IRA man, who is now in prison. IRA rules threaten death for any man caught having an affair with a prisoner’s wife; Danny and Maggie, who are still drawn to each other, are in danger–especially from the militant IRA faction led by Harry (Gerard McSorley), a hothead who hates Hamill, fears Danny, and sees the forbidden relationship as a way to destroy them both.

Danny Flynn is no longer interested in sectarian hatred. He joins his old boxing manager, an alcoholic named Ike (Ken Stott), in reopening a local gymnasium for young boxers of all faiths. And he goes into training for a series of bouts himself, becoming a figurehead for those in the community who want to heal old wounds and move ahead. The story, which is constructed in a solid, craftsmanlike way by Sheridan and his co-writer, Terry George, balances these three elements–the IRA, boxing and romance–in such a way that if elements of one go wrong, the other two may fail as well.

Sheridan is a leading figure in the renaissance of Irish films. His directing credits include “My Left Foot” (1989), with Day-Lewis in an extraordinary performance as Christy Brown, the poet who was trapped inside a paralyzed body; “The Field” (1990), which won Richard Harris an Oscar nomination as a man who reclaims land from a rocky coast, and “In the Name of the Father” (1993), nominated for seven Oscars and starring Day-Lewis as a Belfast man wrongly accused of bombings. He also co-wrote Mike Newell’s comedy “Into the West” (1993) and Terry George’s “Some Mother’s Son” (1996), about the mothers of hunger strikers in the Maze prison. George is his frequent collaborator. His films are never exercises in easy morality, and “The Boxer” is more complex than most. Apart from Danny and Maggie, film’s key figure is Joe Hamill, played with a quiet, sad, strong center by Brian Cox as a man who has, in his time, killed and ordered killings–but has the character to lead his organization toward peace. Harry, the bitter militant, lost a child to the British, and accepts no compromise; if Danny and Maggie act on their love for each other, they may destroy the whole delicate balance.

Against the political material, the boxing acts as a setting more than a world. We see how hot passions are passed along to a younger generation, how boxing can be a substitute for warfare and (in an almost surrealistic scene in a black-tie private club in London) how the rich pay the poor to bloody themselves.

What’s fascinating is the delicacy of the relationship between Maggie and Danny. Played by two actors who have obviously given a lot of thought to the characters, they know that love is not always the most important thing in the world, that grand gestures can be futile ones, that more important things are at stake than their own gratification, that perhaps in the times they live in romance is not possible. And yet they hunger. Day-Lewis and Watson (from “Breaking the Waves“) are smart actors playing smart people; when they make reckless gestures, it is from despair or nihilism, not stupidity.

The film’s weakness is in its ambition: It covers too much ground. Perhaps–I hate to say it–the boxing material is unnecessary, and if the film has focused only on the newly released prisoner, his dangerous love and the crisis in IRA politics, it might have been cleaner and stronger. There are three fights in the film, and the outcome of all three is really just a distraction from the much more important struggles going on outside the ring.