By Roger Ebert

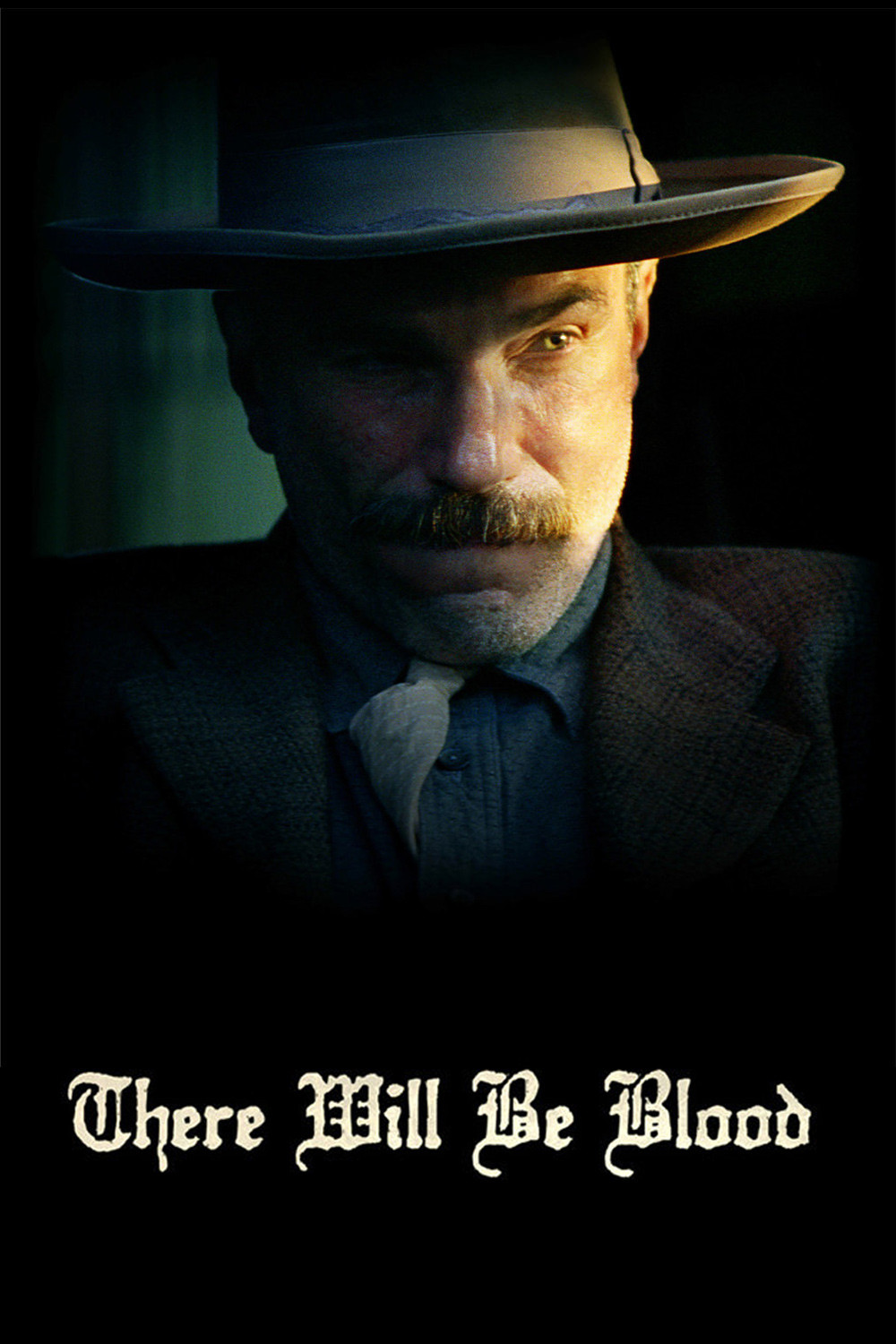

The voice of the oil man sounds made of oil, gristle and syrup. It is deep and reassuring, absolutely sure of itself, and curiously fraudulent. No man who sounds this forthright can be other than a liar. His name is Daniel Plainview, and he must have given the name to himself as a private joke, for little that he does is as it seems. In Paul Thomas Anderson’s brutal, driving epic “There Will Be Blood,” he begins by trying to wrest silver from the earth with a pick and shovel, and ends by extracting countless barrels of oil whose wealth he keeps all for himself. Daniel Day-Lewis makes him a great oversize monster who hates all men, including therefore himself.

Watching the movie is like viewing a natural disaster that you cannot turn away from. By that I do not mean that the movie is bad, any more than it is good. It is a force beyond categories. It has scenes of terror and poignancy, scenes of ruthless chicanery, scenes awesome for their scope, moments echoing with whispers and an ending that in some peculiar way this material demands, because it could not conclude on an appropriate note — there has been nothing appropriate about it. Those who hate the ending, and there may be many, might be asked to dictate a different one. Something bittersweet, perhaps? Grandly tragic? Only madness can supply a termination for this story.

The movie is very loosely based on Oil!, Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel about a corrupt oil family based so loosely, you can see the film, read the book and experience two different stories. Anderson’s character is a man who has no friends, no lovers, no real partners and an adopted son that he exploits mostly as a prop. Plainview comes from nowhere, stays in contact with no one, and when a man appears claiming to be his half-brother, it is not surprising that they have never met before. Plainview’s only goal in life is to become enormously wealthy, and he does so, reminding me of “Citizen Kane” and Mr. Bernstein’s observation, “It’s easy to make a lot of money, if that’s all you want to do is make a lot of money.”

“There Will Be Blood” is no “Kane” however. Plainview lacks a “Rosebud.” He regrets nothing, misses nothing, pities nothing, and when he falls down a mine shaft and cruelly breaks his leg, he hauls himself back up to the top and starts again. He gets his break in life when a pudding-faced young man named Paul Sunday (Paul Dano) visits him and says he knows where oil is to be found, and will share this information for a price. The oil is to be found on the Sunday family ranch, where Standard Oil has already been sniffing around, and Plainview obtains the drilling rights cheaply from old man Sunday. There is another son, named Eli, who is also played by Paul Dano, and either Eli and Paul are identical twins or the story is up to something shifty, since we never see them both at once.

Eli is an evangelical preacher whose only goal is to extract money from Plainview to build his church, the Church of the Third Revelation. Plainview goes along with him until the time comes to dedicate his first well. He has promised to allow Eli to bless it, but when the moment comes he pointedly ignores the youth, and a lifelong hatred is founded. In images starkly and magnificently created by cinematographer Robert Elswit and set designer Jack Fisk, we see the first shaky wells replaced by vast fields, all overseen by Plainview from the porch of a rude shack, where he sips whiskey more or less ceaselessly. There are accidents. Men are killed. His son is deafened when a well blows violently, and Plainview grows cold toward the boy; he needs him as a prop, but not as a magnet for sympathy.

The movie settles down, if that is the word, into a portrait of the two personalities, Plainview’s and Eli Sunday’s, striving for domination over their realms. The addition of Plainview’s alleged half-brother (Kevin J. O'Connor) into this equation gives Plainview, at last, someone to confide in, although he confides mostly his universal hatred. That Plainview, by now a famous multimillionaire, would so quickly take this stranger at his word is incredible; certainly we do not. But by now Plainview is drifting from obsession through possession into madness, and at the end, like Kane, he drifts through a vast mansion like a ghost.

The performance by Day-Lewis may well win an Oscar nomination, and if he wins he should do the right thing in his acceptance speech and thank the late John Huston. His voice in the role seems like a frank imitation of Huston, right down to the cadences, the pauses, the seeming to confide. I interviewed Huston three times, and each time he spoke with elaborate courtesy, agreeing with everything, drawing out his sentences, and each time I could not rid myself of the conviction that his manner was masking impatience; it was his way of suffering a fool, which is to say, an interviewer. I have heard Peter O’Toole’s famous imitation of Huston, but channeled through O’Toole he sounds heartier and friendlier and, usually, drunk. I imagine you had to know Huston pretty well before he let down his conversational guard.

“There Will Be Blood” is the kind of film that is easily called great. I am not sure of its greatness. It was filmed in the same area of Texas used by “No Country for Old Men,” and that is a great film, and a perfect one. But “There Will Be Blood” is not perfect, and in its imperfections (its unbending characters, its lack of women or any reflection of ordinary society, its ending, its relentlessness) we may see its reach exceeding its grasp. Which is not a dishonorable thing.