When people told me they’d seen “My Beautiful Laundrette” and it was a good movie, I had a tendency to believe them, for who would dare to make a bad movie with such an uncommercial title? The laundry in question is a storefront operation in one of the seedier areas of London, and it is losing money when a rich Pakistani decides to entrust its management to his nephew. But this is not the saga of a laundry. It is the story of two kinds of outsiders in modern London.

The film opens with some uneventful days in the life of its hero, Omar, who is a young man in need of a job. His father is an alcoholic journalist. His uncle Nasser, one of the more successful members of the Pakistani community in London, is a businessman who owns a chain of parking garages and storefront retail shops. He enjoys success in British terms: He has a big house in the country, an expensive car and a British mistress.

Because a man cannot stand by and see a family member fail for lack of opportunity, he gives Omar a job in a parking garage and later turns the laundry over to him. He also suggests that Omar should get married, perhaps even to his own daughter.

There is some doubt, however, about whether Omar will ever get married. Earlier in the film, we have witnessed a strange scene. Omar and friends have been stopped by a gang of punk neofascist Paki-bashers, when Omar walks up fearlessly to their leader, Johnny, and greets him with affection. We discover that the two young men had been lovers and, before long, Johnny abandons his gang to join Omar in the operation of the laundry.

“My Beautiful Laundrette” refuses to commit its plot to any particular agenda, and I found that interesting. It’s not about whether Johnny and Omar will remain lovers or about whether the laundry will be a success. And it’s not about the drunken father or about Nasser’s daughter, who is so bored and desperate that, during a cocktail party, she goes outside and bares her breasts to Omar through the French doors.

The movie is not concerned with plot, but with giving us a feeling for the society its characters inhabit. Modern Britain is a study in contrasts, between rich and poor, between upper and lower classes, between native British and the various immigrant groups — some of which, such as the Pakistanis, have started to prosper. To this mixture, the movie adds the conflict between straight and gay.

Johnny and Omar’s relationship encompasses some subtleties that the movie handles with great delicacy. Although Omar is a member of a nonwhite immigrant group and Johnny is Anglo-Saxon, the realities of their lives are that Omar will probably turn out to be more successful and prosperous than Johnny. He has the advantage of his uncle’s capital, his family connections and his gift at business.

Johnny is a true outsider, with small prospects of success.

There is another outsider in the movie who shares his dilemma. She is Rachel, Nasser’s British mistress. Nasser remains married to his Pakistani wife, and although the two women are more or less known to one another, he keeps them in separate compartments of his life. There is a moment, though, during the opening ceremonies at the laundry, when the two women are accidentally in the same room at the same time. It results in an extraordinary speech by Rachel, who with pride and dignity defends her position as Nasser’s mistress by describing herself as a woman who has never had a break in life, who has always had to ask for what she wanted and who deserves some small measure of happiness, just like anybody else.

A movie like this lives or dies with its performances, and the actors in “My Beautiful Laundrette” are a fascinating group of unknowns, with one exception: Shirley Anne Field, who plays Rachel, and whom you may recognize from “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning” and other British films.

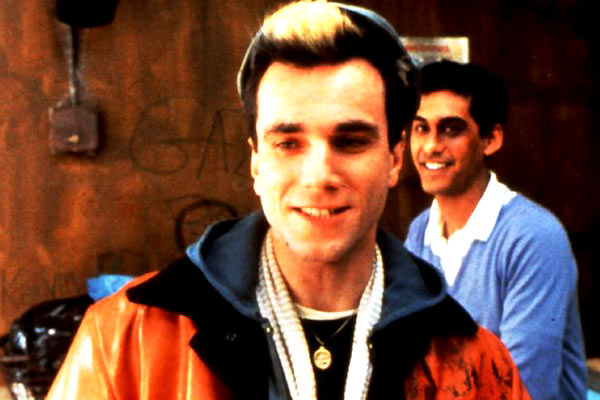

The character of Johnny may cause you to blink if you’ve just seen the wonderful “A Room with a View.” He is played by Daniel Day-Lewis, the same actor who, in “Room,” plays the heroine’s affected fiancee, Cecil. Seeing these two performances side by side is an affirmation of the miracle of acting: That one man could play these two opposites is astonishing.

Omar is played by Gordon Warnecke, an actor unknown to me, as a bright but passive youth who hasn’t yet figured out the strategy by which he will approach the world. He is a blank slate, pleasant, agreeable, not readily showing the sorrows and angers that we figure ought to be inside there somewhere. The most expansive character in the movie is Nasser (Saeed Jaffrey), an engaging hedonist who doesn’t see why everyone shouldn’t enjoy live with the cynical good cheer he possesses.

The viewer is likely to go through a curious process while watching this film. At first there is unfamiliarity: Who are these people, and where do they come from, and what sort of society do they occupy in England? We get oriented fairly quickly and understand the values that are at work. Then we begin to wonder what the movie is about. It is with some relief that we realize it isn’t “about” anything; it’s simply some weeks spent with some characters in a way that tells us more about some aspects of modern Britain than we’ve seen before.

I mentioned “A Room with a View” because of the link with Daniel Day-Lewis. There is another link between the two films. They are both about the possibility of opening up views, of being able to see through a window out of your own life and into other possibilities. Both films argue that you have a choice. You can accept your class, social position, race, sexuality or prejudices as absolutes, and live entirely inside them. Or you can look out the window, or maybe even walk out the door.