Ever since IP-driven cinema took over, we’ve long missed the pleasure of being surprised.

Long before they popped on the screen, we know going into whatever comic book movie or long-standing property what easter eggs or callbacks would be engineered to delight us. Much of blockbuster cinema is now fast-food service, and everyone has seen the menu. But moviegoers shouldn’t have it their way. Their imaginations should be conjured and pushed, stretched and piqued. In situations where a studio decides to revive a crowd favorite, they should allow the filmmakers behind that work to allow their reintroduction to be bold, shocking and weird.

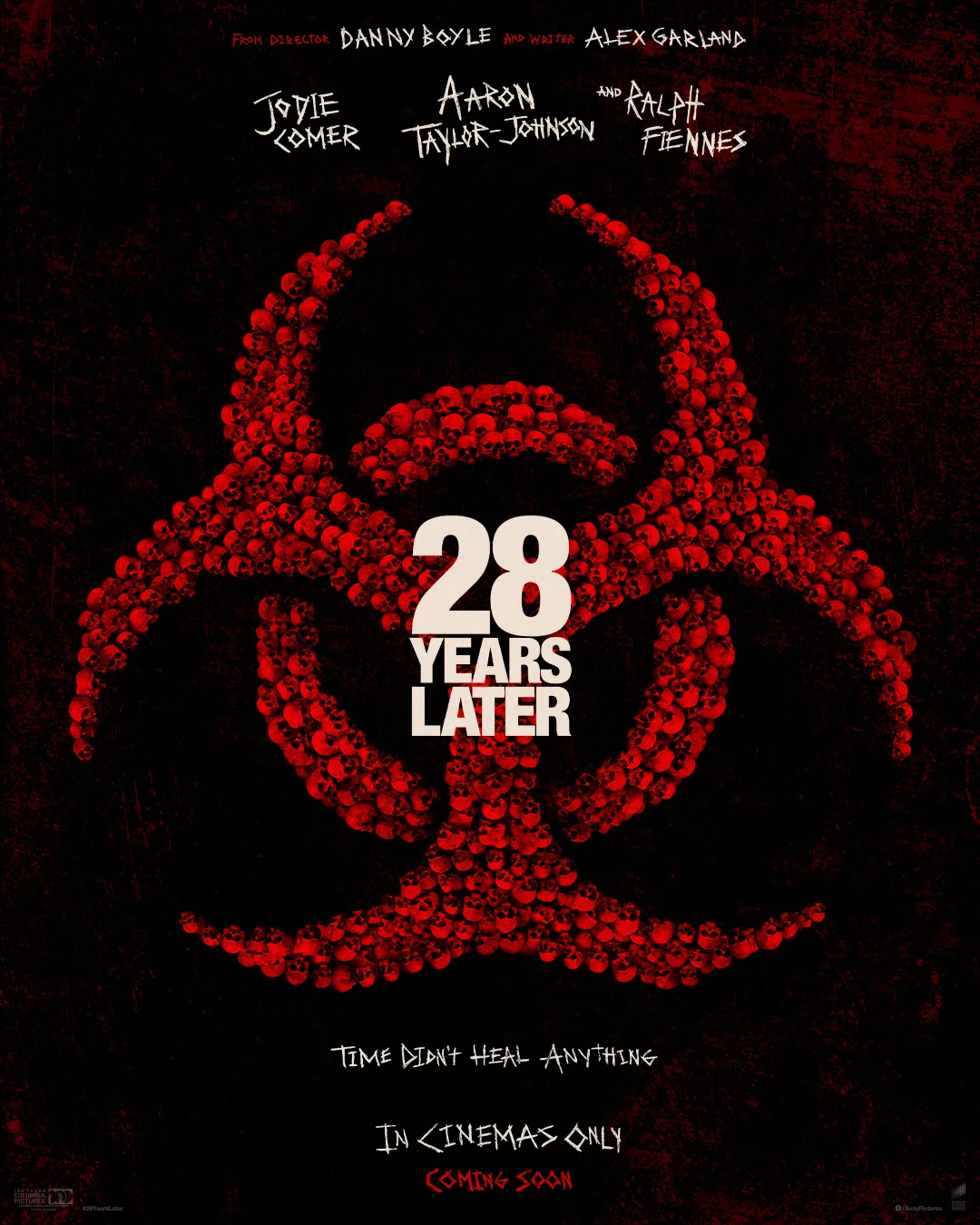

Danny Boyle’s “28 Years Later,” a zombified IP, returns the director to the gory terrain he first forged with the grungy “28 Days Later.” It also sees him reteaming with Alex Garland, who after launching a successful directorial career (“Annihilation”) is back penning a franchise he authored as screenwriter for “28 Days Later,” and produced its sequel “28 Weeks Later.” That’s nearly where the nostalgia ends. Because whatever you think the third edition in this trilogy could be, Boyle and Garland gleefully subvert it. Instead, “28 Years Later,” an at times tonally daring and whimsically transportive coming-of-age zombie film, does the exact opposite of what you expect. Though this horror flick anticipates the coming of the Nia DaCosta helmed sequel “28 Years Later: The Bone Temple,” it refreshingly doesn’t operate by the logic of franchise building. It’s a gnarly piece of gruesome art.

“28 Years Later” is theoretically a zombie movie, until it isn’t. The oddball film begins with a group of children in the Scottish Highlands, during the opening days of a virus rendering many into flesh-eating monsters, watching an episode of the “Teletubbies.” Their momentary peace is interrupted when a hoard of raging flesh eaters come bursting through their cottage doors and windows. While many are slaughtered, one child escapes. He runs to his dad, a priest praying in a church who interprets this wave of destruction as the fruition of Biblical prophecy. Though the father will be consumed, the son will escape. His ultimate fate won’t be revealed until the film’s end. In the meantime, Boyle and Garland, like the trilogy’s other cold opens, push us forward in time. Soon it’s 28 years later, and we’re in a hamlet surrounded by water.

Rather than returning us to London, where the action of the first two films take place, the filmmakers decide to shift us to a Northumberland isle called Holy Island to show us how a quarantined people have created a new isolationist community. Here we settle on a different boy, a 12-year-old Spike (Alfie Williams) preparing to go on his first hunt with his strapping dad Jamie (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). The hunt is a ritual boys go on when they’re 14 or 15 years of age. From the jump, however, we can tell Spike is experienced beyond his years in some ways and inexperienced in others. He idolizes his astute father and cares for his ailing mother Isla (Jodie Comer), a woman so beset by migraines and hallucinations she is bedbound. Their village, an oasis in a sea of terror, is surrounded by water that only recedes during low tide, when a causeway connected to the mainland reveals itself. Boyle stays in this near-cultish village for just long enough to creep us out by presenting their drunken revelries and their religious iconographies.

Pulsating and nightmarish, Spike and Jamie’s journey into the woods reveal some key details about Garland’s world building. There are now several kinds of zombies: some are slow moving obese creatures that crawl on the floor, while others are the naked and twitchy sprinting types. But there’s one that stands above them all, a tall, hulking giant Jamie calls an Alpha, who not only possesses super strength and speed, but is also far more intelligent than his counterparts. The Alpha interrupts Spike’s first hunt, causing father and son to take shelter, where Spike spots a seemingly unexplainable fire in the distance operated by the supposedly insane doctor, Ian Kelson (Ralph Fiennes). Though the pair do eventually return to the village, Spike learns a secret about his father that both causes him to distrust his dad and to abscond back to the mainland with his ailing mother in the hopes that Kelson can provide a cure. What erupts is a kind screwed up “Wizard of Oz,” wherein Spike and his mother meet odd travelers across fields and dales, holding the wish of being healed by this mythical entity.

During Spike’s journey, you expect some bloody freakout moments to happen. And while some do occur, with kill shots whose freeze frames often recall Garland’s “Civil War,” the zombies assume the back burner. Instead, Boyle opts for a Brothers Grimm vibe. Spike meets an antsy pregnant zombie and a Swedish soldier carrying news of the outside world. He also cares for his mother in between her moments of lucidity and hallucination. In these scenes, lush verdant fields and forest green trees take on a fairytale sheen that differs from the grunge of “28 Days Later” and the harsh kineticism of “28 Weeks Later.” That softer lens doesn’t mean cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle’s imagery lose any immediacy. The colors wrap you in a dewy dream knowingly juxtaposed from the apathy of this deadly world.

For several reasons, “28 Years Later” shouldn’t work. On top of the “Teletubbies” pull, Boyle includes archival footage of British war films intercut with scenes of Spike’s village training themselves. Boyle never really returns to this militarist fervor, except for the appearance of the aforementioned Swedish soldier. He also doesn’t really dive deep into the religious critique he’s halfway set up. With the latter, we can probably forgive him in anticipation of a sequel harvesting such fertile ground. But considering the conversation “28 Weeks Later” initiated on the topic of militarism, however, that theme seems lacking here.

Still, this film thrills because of the commitment of Boyle to his vision, and the actors willing to come along for this zany ride. Comer, for instance, provides hints of absurdity and vulnerability, oscillating between dazed and confused and painstakingly aware of the burden undertaken by a son asked to mature beyond his years. Unbridled fear gives way to touching and lighthearted moments of frivolity, embolden by Young Fathers’ ethereal music. Williams is also a revelation as a kid who eschews cuteness while confronting his own naivete. Meanwhile, Fiennes strongly emerges to give screwy scenes soft notes of touching finality that should crumble under the weight of their own folly.

“28 Years Later” is a deeply earnest film, a picture whose sincerity is initially off putting until it’s endearing. Toward the end, through the concept of “memento mori,” this zombie picture attempts to grapple with the toll of the onscreen death that’s filled viewers’ minds for decades now. It’s a desire that isn’t inspired by a need to craft elongated arcs, future callbacks or even the return of former characters. The decision to consider the finality of death and how we remember those who’ve passed on is a gesture to the human in a franchise filled with the inhuman. Rather than needling our instinct to run, Boyle commands us to stop and mourn, to remember and grieve. Many more days, weeks and years will pass, but the surprise that is “28 Years Later” has our attention now.