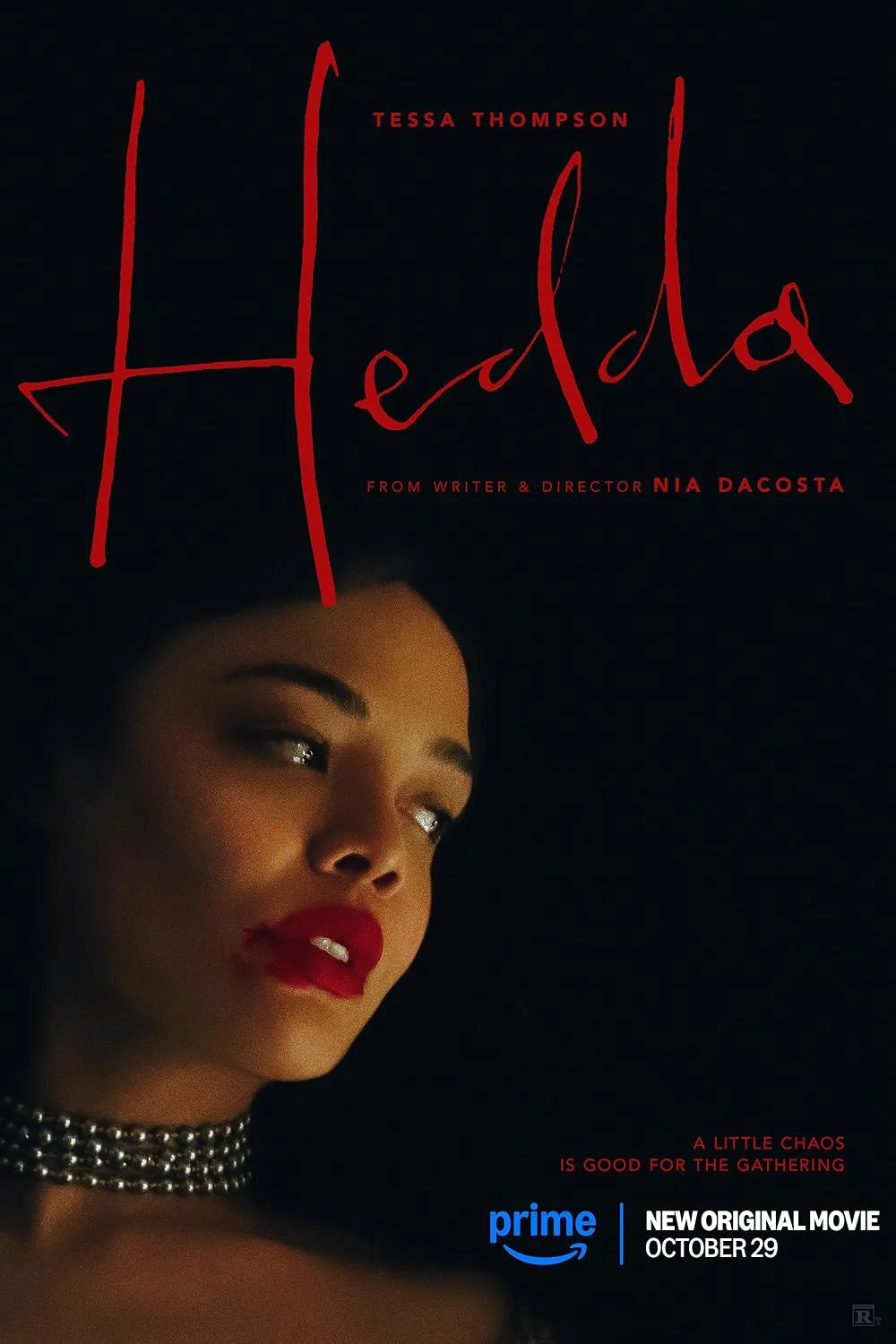

“Hedda,” writer-director Nia DaCosta‘s latest film, puts a queer spin on Henrik Ibsen’s 1891 play Hedda Gabler. Set in early 20th-century England, DaCosta reunites with Tessa Thompson, who starred in the searing debut “Little Woods,” as the titular Hedda, a recently married woman from a good family whose desire for further wealth has put her academic husband George (Tom Bateman) into debt. Hedda, the “bastard” daughter of the late General Gabler, loves guns and playing with people’s emotions.

The couple has recently returned from their extended honeymoon abroad to a country estate they cannot really afford. That is, unless George gets a prestigious professorship and an endowment at the university where he teaches. Hedda devises a party allegedly to help him achieve this goal, inviting his superior, Professor Greenwood (Finbar Lynch, fine), and his young wife Tabitha (Mirren Mack), along with a myriad of Hedda’s bohemian friends. Things appear to be going well until the arrival of fellow academic Eileen Lovborg (Nina Hoss), a recently sober alcoholic and Hedda’s ex-lover, who has been gender-switched from Ibsen’s play. As Hedda manipulates to undo all the work that Eileen’s new companion, Thea (Imogen Poots), has done to sober her up, her real objective for the party becomes clear.

Ibsen’s original work deployed Hedda’s psychological cat-and-mouse game over four acts, while DaCosta has split her film into five, denoting the structure with title cards fits as is the recent trend of filmmakers delineating their films with chapters, and the mechanics of everyone’s mental decline is well plotted, however the tension of the night is deflated by DaCosta’s choice to open her film with a stinger from the final act, as if she felt she must let the audience know right away that death was lingers at Hedda’s doorstep, rather than let that revelation grow as the the party—and the film—progresses.

DaCosta’s script is full of allusions to Hedda’s past as a fiery woman and voracious lover, implying that she’s likely slept with everyone, regardless of gender, who is at her party. We see her assess the weaknesses of people and expertly play them like a violin, getting precisely what she wants exactly when she wants it. Her little barbs and these sapphic allusions account for much of the film’s humor, which played incredibly well with the audience at its world premiere at TIFF, where the film elicited moments of laughter as well as audible reactions of wonder. One shocking moment ended with the film in stunned silence, and then a man simply went, “wow.”

Yet, “Hedda” is a movie whose ambitions I admire, but whose execution is lacking. I found Oscar-winner Hildur Guðnadóttir’s score overwhelming, used as a crutch to dictate how I should feel at any given moment. Every time Hedda does something manipulative, the moment is punctuated with breathy vocalizations, taking a cue seemingly from the Showtime teenage cannibal series “Yellowjackets.”

The editing of the film is clunky, DaCosta and DP Sean Bobbitt’s compositions are bland, and the film’s lighting during the extended party sequence is murky. I was shocked when, in the final sequence, which is filmed with natural light at dawn, the dress Hedda wears all night is in fact green, not the bland grey it appears for most of the film’s runtime. The party sequences themselves were clearly a lot of fun to film, but are undercut by strange framing and editing choices, as well as the filmmakers’ inability to effectively capture the flow of dance in a way that soars as brightly as the jazz music they’re dancing to.

For their parts, Thompson (in a purposely staccato British accent), Hoss, and especially Poots give impassioned performances that are let down by DaCosta’s strange framing choices. At the same time, the men are never allowed much depth or even really many differentiating characteristics. In some of the film’s most emotionally raw scenes, DaCosta seems to be allergic to giving her actors their due close-up, instead filming in weirdly distant medium shots, under-lit profile shots, or some unnecessary and unflatteringly oblique angle.

The only scene in which the filmmaking matches the emotional wavelength of the character comes during Eileen’s arrival. When Hedda sees her former lover, a torch for whom Hedda clearly carries in her heart, from across the dance floor, her eyes light up with desire, and she glides in ecstasy across the room via a stunning double dolly shot, a clear homage to Spike Lee.

If only there were more flourishes in DaCosta’s film that made emotional sense, or came as close to touching that kind of cinematic greatness. Instead, the film largely feels like an echo of something that was once great, a bit like the dilapidated manor in which the party takes place, and can’t quite reach the height of its own ambition.

This review was filed from the premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 8. It opens in theaters on October 22, 2025, before moving to Prime Video October 29.