Activists set lab animals free from their cages–only to learn, too late, that they’re infected with a “rage” virus that turns them into frothing, savage killers. The virus quickly spreads to human beings, and when a man named Jim (Cillian Murphy) awakens in an empty hospital and walks outside, he finds a deserted London. In a series of astonishing shots, he wanders Piccadilly Circus and crosses Westminster Bridge with not another person in sight, learning from old wind-blown newspapers of a virus that turned humanity against itself.

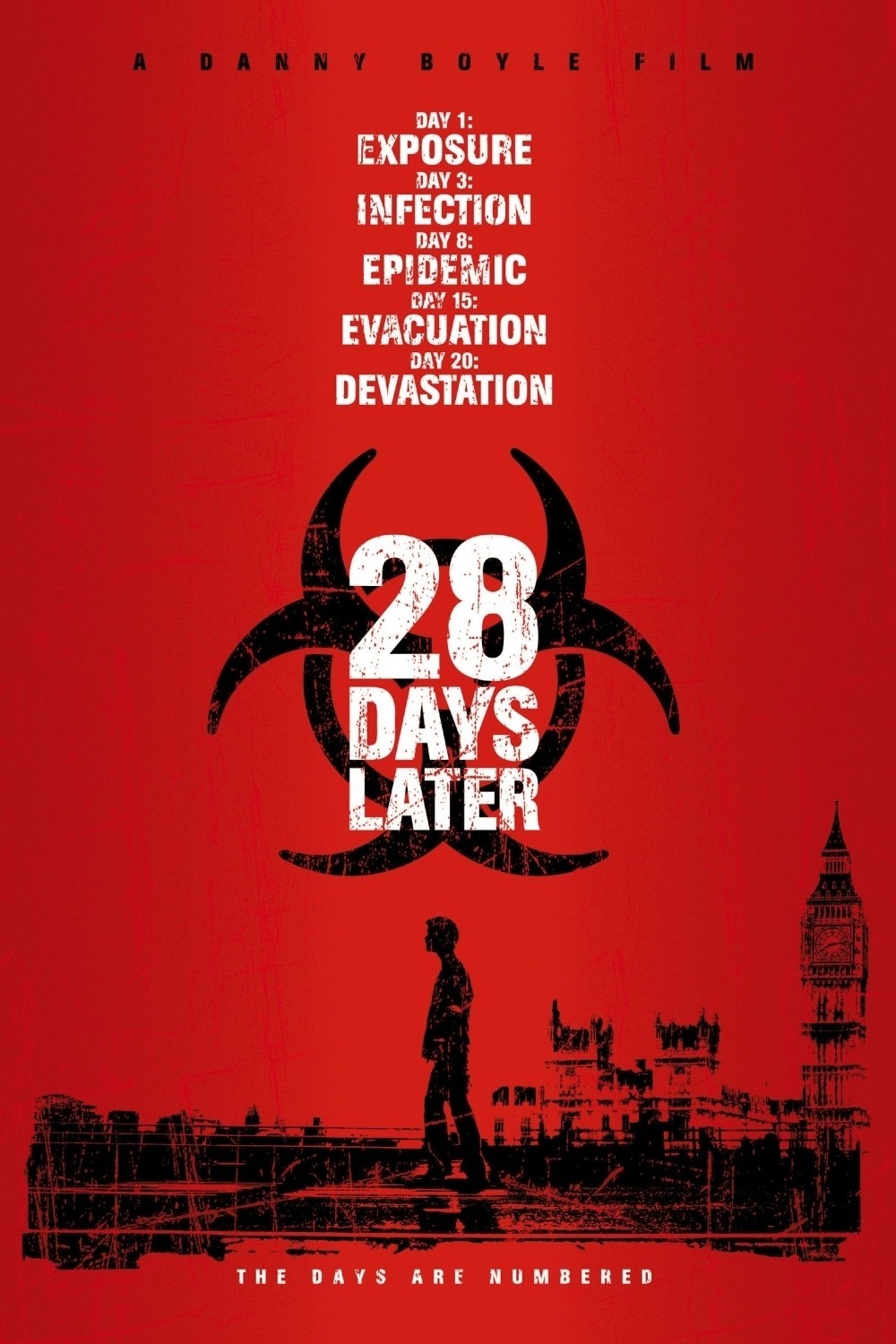

So opens “28 Days Later,” which begins as a great science fiction film and continues as an intriguing study of human nature. The ending is disappointing–an action shoot-out, with characters chasing one another through the headquarters of a rogue Army unit–but for most of the way, it’s a great ride. I suppose movies like this have to end with the good and evil characters in a final struggle. The audience wouldn’t stand for everybody being dead at the end, even though that’s the story’s logical outcome.

Director Danny Boyle (“Train-spotting”) shoots on video to give his film an immediate, documentary feel, and also no doubt to make it affordable; a more expensive film would have had more standard action heroes, and less time to develop the quirky characters. Spend enough money on this story, and it would have the depth of “Armageddon.” Alex Garland’s screenplay develops characters who seem to have a reality apart from their role in the plot–whose personalities help decide what they do, and why.

Jim is the everyman, a bicycle messenger whose nearly fatal traffic accident probably saves his life. Wandering London, shouting (unwisely) for anyone else, he eventually encounters Selena (Naomie Harris) and Mark (Noah Huntley), who have avoided infection and explain the situation. (Mark: “OK, Jim, I’ve got some bad news.”) Selena, a tough-minded black woman who is a realist, says the virus had spread to France and America before the news broadcasts ended; if someone is infected, she explains, you have 20 seconds to kill them before they turn into a berserk, devouring zombie.

That 20-second limit serves three valuable story purposes: (a) It has us counting “12 … 11 … 10” in our minds at one crucial moment; (b) it eliminates the standard story device where a character can keep his infection secret; and (c) it requires the quick elimination of characters we like, dramatizing the merciless nature of the plague.

Darwinians will observe that a virus that acts within 20 seconds will not be an efficient survivor; the host population will soon be dead–and along with it, the virus. I think the movie’s answer to this objection is that the “rage virus” did not evolve in the usual way, but was created through genetic manipulation in the Cambridge laboratory where the story begins.

Not that we are thinking much about evolution during the movie’s engrossing central passages. Selena becomes the dominant member of the group, the toughest and least sentimental, enforcing a hard-boiled survivalist line. Good-hearted Jim would probably have died if he hadn’t met her. Eventually they encounter two other survivors: A big, genial man named Frank (Brendan Gleeson) and his teenage daughter Hannah (Megan Burns). They’re barricaded in a high-rise apartment, and use their hand-cranked radio to pick up a radio broadcast from an Army unit near Manchester. Should they trust the broadcast and travel to what is described as a safe zone? The broadcast reminded me of that forlorn radio signal from the Northern Hemisphere that was picked up in post-A-bomb Australia in “On the Beach.” After some discussion, the group decides to take the risk, and they use Frank’s taxi to drive to Manchester. This involves an extremely improbable sequence in which the taxi seems abler to climb over gridlocked cars in a tunnel, and another scene in which a wave of countless rats flees from zombies.

Those surviving zombies raise the question: How long can you live once you have the virus? Since London seems empty at the beginning, presumably the zombies we see were survivors until fairly recently. Another question: Since they run in packs, why don’t they attack one another? That one, the movie doesn’t have an answer for.

The Manchester roadblock, which is indeed maintained by an uninfected Army unit, sets up the third act, which doesn’t live up to the promise of the first two. The officer in charge. Maj. Henry West (Christopher Eccleston) invites them to join his men at one of those creepy movie dinners where the hosts are so genial that the guests get suspicious. And then… see for yourself.

Naomie Harris, a newcomer, is convincing as Selena, the rock at the center of the storm. We come to realize she was not born tough, but has made the necessary adjustments to the situation. In a lesser movie, there would be a love scene between Selena and Jim, but here the movie finds the right tone in a moment where she pecks him on the cheek, and he blushes. There is also a touching scene where she offers Valium to young Hannah. They are facing a cruel situation. “To kill myself?” Hannah asks. “No. So you won’t care as much.” The conclusion is pretty standard. I can understand why Boyle avoided having everyone dead at the end, but I wish he’d had the nerve that John Sayles showed in “Limbo” with his open ending. My imagination is just diabolical enough that when that jet fighter appears toward the end, I wish it had appeared, circled back–and opened fire.

But then I’m never satisfied. “28 Days Later” is a tough, smart, ingenious movie that leads its characters into situations where everything depends on their (and our) understanding of human nature.